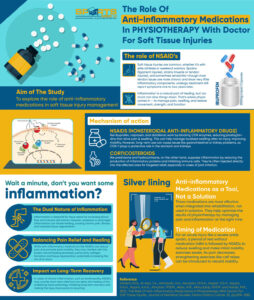

The Role of Ant-Inflammatory Medication in Physiotherapy

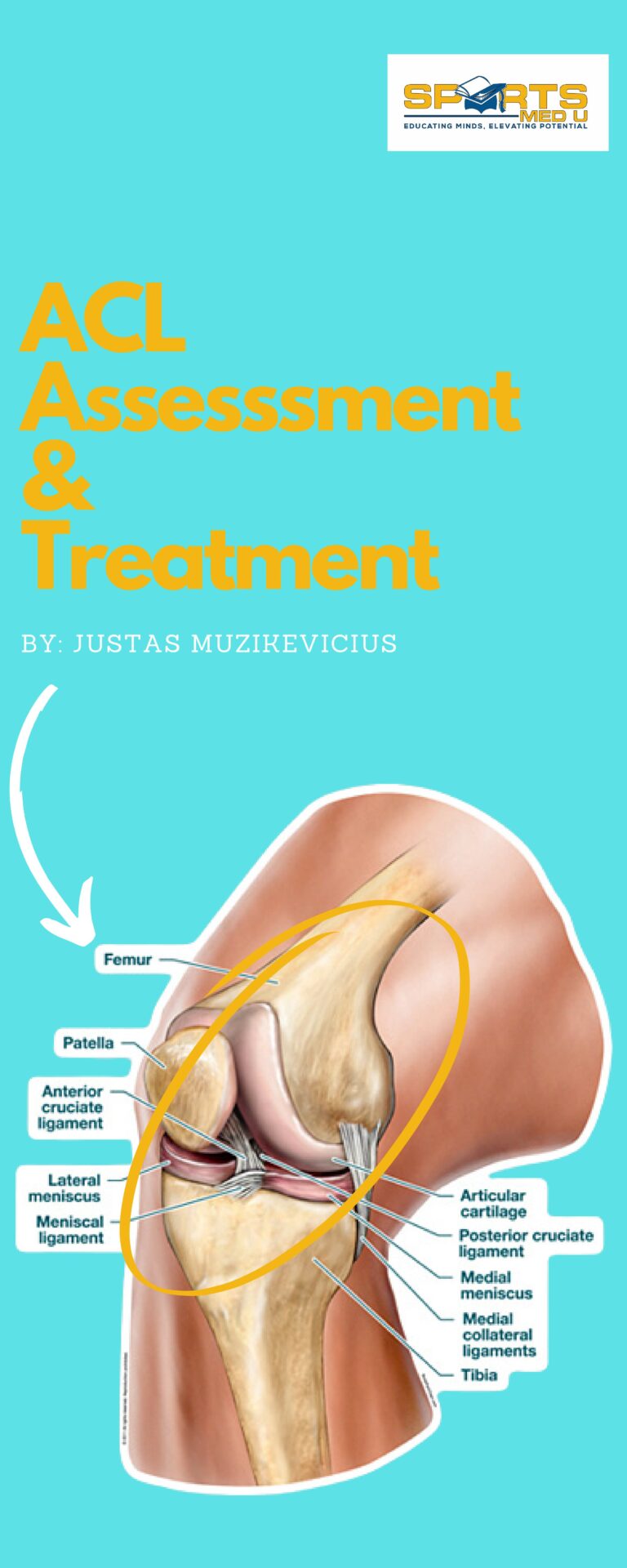

Soft tissue injuries—whether it’s a weekend warrior’s twisted ankle or an elite athlete’s strained hamstring—are a common challenge in physiotherapy. Pain, swelling, and reduced mobility can derail recovery, making effective treatment essential.

But here’s the big question: should we always be fighting inflammation?

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) are the go to when we want to manage an inflammatory condition. They’re often prescribed to manage pain and swelling, but their role in recovery is more complex than simply turning off inflammation.

In fact, using them at the wrong time or in the wrong way could actually slow healing rather than speed it up.

If you’ve ever wondered how NSAIDs work, when they should (and shouldn’t) be used in physiotherapy, and what the science really says about their impact on recovery, you’re in the right place.

This article breaks down the findings of a study by Alshehri and colleagues, which takes a deep dive into the mechanisms, benefits, and potential drawbacks of NSAID use in rehabilitation.

The bulk of the information comes from their research, so you can be confident you’re getting evidence-based info—translated into practical, real-world applications for physiotherapists.

Let’s dive in and separate fact from fiction

In A Nutshell

Rapid Results:

NSAIDs can hinder the healing process in acute injuries and disrupt the stomach lining and renal function. However, it can also help with early mobilisation if used sensibly and strategically

Professional Takeaway:

Suggest NSAIDs for short durations, no longer than 5-7 days, to manage acute symptoms. After this period, the emphasis should be on rehabilitation rather than pharmacological interventions.

Did You Know?

Soft tissue injuries are common and often debilitating no matter if it’s a high level athlete or (and I would argue even more commonly) if its a weekend warrior.

Most frequently you will see 1 of 3 types:

- Sprains (ligament injuries)

- Strains (muscle or tendon injuries)

- Tendonitis (inflammation of tendons)

Now, I’m not the biggest fan of the description tendonitis as that implies an inflammation. Most tendon issues are chronic and tend to have very little of the inflammatory component. But sometimes, tendonitis is the correct diagnosis.

This is how to distinguish one from the other,

Tendinopathy is a term that describes chronic tendon disorders (3 months or longer) patients will complain of pain, stiffness, and reduced function.

It typically involves degenerative changes in the tendon structure (collagen disorganisation, increased ground substance) rather than inflammation, often due to overload or repetitive strain.

Tendonitis on the other hand refers specifically to acute inflammation of a tendon, usually caused by sudden injury or excessive loading. It has the classic signs of inflammation, such as redness, swelling, and warmth, with minimal structural changes in the tendon itself

These injuries (the 3 i mentioned at first) can come from acute trauma, like twisting an ankle during a football game, or overuse, as seen in achilles tendon with excessive sprinting and jumping

As I eluded a little earlier the body’s natural healing process includes inflammation, which causes redness, swelling, and pain but can also delay recovery if excessive.

As physios our main role when treating these injuries is to restore movement, strength, and functionality. Anti-inflammatory medications CAN help by addressing the pain and inflammation that could otherwise hinder the effectiveness of physiotherapy.

Their integration into treatment is especially valuable when pain limits a patient’s ability to participate in rehab.

Mechanism Of Action

Anti-inflammatory medications primarily target the inflammatory response that come from soft tissue injuries, like sprains, strains, or tendon issues.

They work by reducing

- Inflammation

- Pain

- Swelling

If not handled the above can hinder the recovery process and cause significant discomfort.

Two major classes anti-inflammatory medications—Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids—function through different but complementary mechanisms.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs, are medication such as ibuprofen, naproxen, and diclofenac, inhibit the action of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, specifically COX-1 and COX-2.

These enzymes are responsible for converting arachidonic acid into prostaglandins, lipid compounds that amplify inflammation, pain, and fever. By blocking COX activity,

NSAIDs reduce prostaglandin production, resulting in decreased swelling and pain at the injury site.

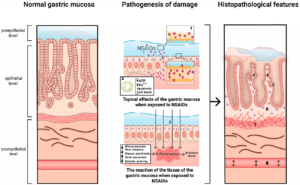

For example, after a sprain, taking ibuprofen can help control localised swelling, allowing for earlier mobility. However, COX-1 also has a protective role in the stomach lining and renal function, which is why prolonged NSAID use can cause gastrointestinal or kidney issues.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids like prednisone, dexamethasone, or hydrocortisone are synthetic versions of hormones produced by the adrenal glands. These medications bind to glucocorticoid receptors inside cells, which triggers changes in gene expression and suppresses the production of inflammatory proteins, such as cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α).

Corticosteroids also inhibit immune cell activity, such as macrophages and lymphocytes, reducing tissue damage. For localised relief, corticosteroids are often injected directly into “inflamed” areas like tendon joints, to minimise systemic side effects.

Don’t You Want Some Inflammation?

Inflammation is a physiological response to injury, essential for initiating tissue repair and protecting against infection. However, the role of inflammation is complex, as both excessive and prolonged inflammation can hinder the healing process.

Anti-inflammatory medications are commonly used in clinical practice to modulate this response, yet their use requires careful thought due to the potential side effects and impact on tissue repair.

The Dual Nature of Inflammation in Tissue Healing:

Inflammation is a double-edged sword.

On one hand, it promotes repair by increasing blood flow, facilitating immune cell recruitment, and removing damaged tissue.

On the other hand, excessive or unresolved inflammation can lead to chronic pain, fibrosis, and impaired tissue regeneration.

Acute inflammation involves the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, prostaglandins, and growth factors like transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), which orchestrate the repair process by stimulating collagen production and tissue regeneration.

Chronic inflammation, however, leads to the persistent activation of immune cells, ongoing release of inflammatory mediators, and can cause excessive collagen deposition, resulting in scar tissue formation and long-term dysfunction.

The Impact on Tissue Healing:

One of the most significant issues in the integration of anti-inflammatory medications with physiotherapy is the potential for impaired healing.

While reducing inflammation and pain may promote early mobilisation, it also reduces the body’s natural repair mechanisms. Hence a need for a balance between pain relief and the potential detriment to tissue regeneration.

For instance, early mobilisation facilitated by NSAIDs may allow for increased range of motion and strength, but this may come at the cost of collagen formation or increased susceptibility to re-injury if the healing tissue has not fully matured.

Furthermore, excessive anti-inflammatory use, especially in chronic conditions, can alter the course of recovery.

In cases like tendonitis, NSAIDs may provide short-term symptom relief but can delay the resolution of the underlying tissue pathology, preventing long-term recovery and increasing the risk of recurring injury.

Benefits In Physiotherapy

Now, the caveats out of the way, let’s discuss how NSAID’s can help in practice.

- Pain Relief One of the most immediate benefits of anti-inflammatory medications, especially NSAIDs, is pain relief. Pain is a primary barrier in physiotherapy, and managing it can help patients engage more effectively in rehab. NSAIDs work by reducing inflammation, which in turn decreases the pain signals sent to the brain.

- Reduction of Inflammation and Swelling Inflammation and swelling are natural responses to injury but can also delay recovery. Reducing inflammation is importnat as it allows the healing process to progress without unnecessary complications. Anti-inflammatory medications, particularly corticosteroids and NSAIDs, target inflammatory mediators and decrease swelling at the site of injury.

- Facilitation of Early Mobilisation Early mobilisation is critical in the rehab process to prevent joint stiffness and maintain soft tissue function. Anti-inflammatory medications helps patients to take the first step and start loading the area sensibly, with less discomfort. By decreasing symptoms with early loading, these medications can hep reduce the recovery time frames and the likelihood of long-term functional limitations.

Other Issues You Should be Aware Off

Despite the benefits mentioned above, anti-inflammatory medications come with other risks that must be carefully managed. NSAIDs, for example, can irritate the stomach lining, leading to gastritis or ulcers, especially with prolonged use or when taken on an empty stomach.

Patients with existing conditions like acid reflux or kidney disease are particularly vulnerable.

In sports medicine, athletes who overuse NSAIDs to “push through” pain might mask symptoms, leading to further injury—like a runner with a stress fracture worsening their condition by continuing training.

Corticosteroids have their own set of risks. Repeated injections can weaken tendons and cause rupture, as seen in some cases of Achilles tendinopathies.

These medications can also suppress the immune system, increasing susceptibility to infections.

Given these risks, It’s importnat to emphasise short-term use.

The Silver Lining

The real power of anti-inflammatory medications lies in the integration with rehabilitation at the right time and for the right amount of time .

They’re NOT standalone solutions but tools to help optimise the effectiveness of physiotherapy. For example, after a severe ankle sprain give 48 hours of rest with no medication and after start a course of NSAIDs as it can reduce swelling & make it easier to perform initial mobility exercises like ankle circles and weight bear.

As discomfort eases, you can introduce strengthening exercises, such as calf raises (if appropriate), to rebuild stability.

Corticosteroid injections are often reserved for chronic cases where inflammation severely limits progress.

For example, a swimmer with persistent shoulder bursal pain might receive an injection to relieve pain, allowing them to start targeted strengthening.

The ultimate goal of physiotherapy is to address biomechanical “kinks” and improve movement patterns. Anti-inflammatory medications facilitate this process by creating a window of opportunity for effective intervention

Clinical Tips

Balance Pain Management and Tissue Healing

Use anti-inflammatory medications only in the acute phase (first 48-72 hours) to manage pain and swelling, but avoid prolonged use. Prolonged NSAID use can inhibit collagen synthesis and hinder tissue repair, especially in tendon injuries.

After the acute phase, you can try shifting the focus to manual therapy to promote by product clearance and blood flow without compromising tissue regeneration.

Timeframe: Use NSAIDs for short durations, no longer than 5-7 days, to manage acute symptoms. After this period, the emphasis should be on rehabilitation rather than pharmacological interventions.

Gradual Progression in Rehabilitation:

Early mobilisation is important, but ensure that exercises are progressed gradually to avoid over stressing healing tissues. Start with pain-free range of motion and gentle isometric exercises in the early stages, progressing to more dynamic strengthening and functional exercises as the tissue heals and becomes stronger.

There is no size that fits all, thus let the patient and their symptoms guide the treatment. A little bit of discomfort is to be expected.

Monitor for Excessive Inflammation:

Assess inflammation regularly using clinical signs (increased pain, swelling, heat, loss of function). If inflammation persists beyond the acute phase, consider adjusting treatment to focus on reducing this prolonged inflammation. Consider using cold, compression, and very light soft tissue work

Timeframe: For the first 72 hours, focus heavily on managing acute inflammation. After that, modify the treatment to promote healing without suppressing the necessary inflammatory processes that support tissue repair.

Consider the Risk of Corticosteroids:

Be mindful when recommending the use of corticosteroid injections, especially in tendon injuries. Corticosteroids may reduce inflammation quickly but can weaken tendons over time, increasing the risk of re-injury. Use corticosteroids sparingly and as a last resort, especially in cases of severe acute inflammation that are unresponsive to conservative treatment.

Timeframe: Corticosteroid injections should be considered only after other conservative treatments have failed and should be used with caution. Limit use to 1-2 injections per year per tendon to minimise risks.

Reference:

- Alshehri, M.G., Al-Asiri, Y.A., Althobaiti, A.G., Alsufyani, M.M.A., Alzaidi, Y.G.M., Alyami, H.A.H., Alyami, A.A.H., Almotairi, M.B.M., Aldor, A.M., Alkhudaidy, R.M.M. and Halabi, M.K., 2022. The Role Of Anti-Inflammatory Medications In Physiotherapy With Doctor For Soft Tissue Injuries. Journal of Namibian Studies: History Politics Culture, 32, pp.1574-1585.

Leave a Reply