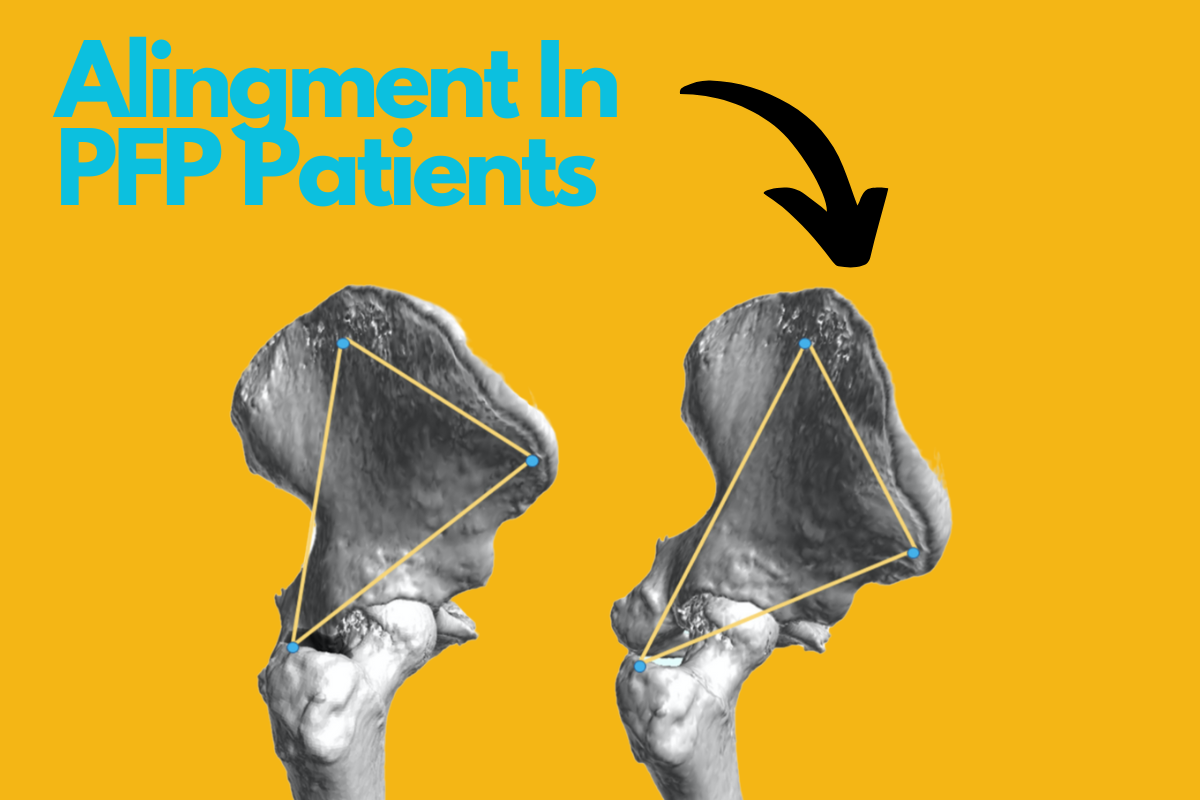

Patello-femoral Pain – How Does Alignment Contribute?

If you ever encountered patellofemoral pain (and if you’re a physio you definitely have) you know how persistent and frustrating this condition can be.

Fortunately, we have more tools than ever to help treat it effectively, and one of the most interesting studies on this topic comes from Stephen and colleagues.

In this article, we’ll break down their findings and apply them to real-world rehab principles.

The study looks into factors like

- Movement patterns

- Muscle function

- Skeletal alignment

All important elements when managing PFP.

By the end of this article, you’ll have a clearer understanding of how alignment contributes to rehabilitation and how you can implement these findings to improve patient outcomes.

Let’s dive in!

In A Nutshell

Rapid Results:

At its core, PFP rehabilitation is a puzzle. The body’s movements are the result of co-ordinated interaction between muscles, joints , and tendons.

Even small deviations in alignment can have ripple effects to force distribution, altering how muscles work and increasing strain.

Retraining movement patterns to optimise muscle efficiency and reduce joint loading, can improve function and decrease injury risk.

Professional Takeaway:

Begin with basic, isolated movements (e.g., hip extension) and gradually advance to more complex, multi-joint exercises (e.g., squats or stair climbing) as patients gain control. This gradual progression ensures patients maintain form and lowers the risk of re-injuring the knee when introducing more demanding tasks.

Did You Know?

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) is a surprisingly common condition, especially in adolescents, with more than 1/4 of them affected. If you think it’s just a fleeting issue, think again—about 40-56% of people who undergo treatment still report symptoms one to two years later.

This persistence makes PFP a condition that deserves serious attention from researchers, clinicians, and patients alike.

What’s even more concerning is that PFP doesn’t just go away. There’s growing evidence that experiencing PFP during the younger years can increase the risk of developing patellofemoral joint (PFJ) osteoarthritis later in life.

Osteoarthritis is a chronic condition that can cause pain, reduced mobility, and even psychological issues like anxiety and depression. So, while PFP might start as a frustrating ache, it has the potential to ripple out into far more significant health challenges if not managed effectively.

Why Is The Patellofemoral Joint So Vulnerable?

The patellofemoral joint (PFJ) handles loads that are often many times the body weight, and it does so through a large range of motion. Its asymmetrical shape helps it adapt to these forces but also makes it prone to irritation. Given the sheer magnitude of the stress it absorbs during running, squatting, or even sitting for long periods, it’s no surprise that it’s a hotspot for pain.

In fact, these types of activities, which significantly load the PFJ, are often the very triggers for PFP symptoms.

So, what do we do about it?

We can teach the PFJ how manage and load more effectively through exercise and activity modification

This is why physiotherapy is considered the gold standard of PFP management. It’s evidence-based, practical, and can yield significant improvements if done correctly and consistently.

That being said, as promising as this approach is, the poor recovery rates show that theres still a lot to learn about treatment for this stubborn condition.

Movement Patterns

PFP is a prime example of how complex musculoskeletal conditions can be.

When someone has PFP, they don’t just have a sore knee. It’s a combination of biomechanical and muscle activation hiccups.

For example, studies show altered movement patterns, like reduced knee flexion when climbing stairs. This could be a subconscious strategy to protect the knee or a result of movement fear (kinesiophobia).

What about the quads? Well the debate gets is interesting.

Historically, the vastus medialis oblique (VMO) was seen as the main contributor in lateral patellar tracking, but modern research says it’s not that simple. Muscle weakness isn’t limited to the VMO; it occurs across the entire quadriceps.

That’s why general strengthening is effective—no need to isolate one muscle, make it simple and focus on supporting the whole system.

Is it complicated? (yes it is)

The knee is not the only area we should think about.

The hips also contribute, though inconsistently. Depending on the person, both excessive or limited hip rotation and strength might contribute to PFP. This variability makes it tough to pin down universal treatment strategies.

Adding to the challenge are the tools we use to study PFP.

Motion capture systems and EMG technology are useful but imperfect. For example, movement markers on the skin might misrepresent what’s happening inside the joint, and EMG readings can get muddied by signals from nearby muscles.

These limitations mean researchers are often left with conflicting results, making it hard to draw clear conclusions.

Ultimately, PFP is a puzzle with many pieces. Its causes and treatment aren’t one-size-fits-all, and that’s what makes it both frustrating and fascinating

Alignment & Management

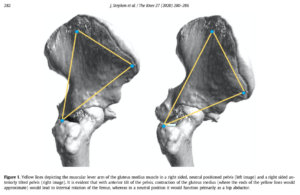

First off, muscles don’t operate in isolation—they’re part of a system that’s influenced by joint positions and mechanical leverage.

Let’s take the gluteus medius, for example. It’s the main contributor for hip abduction, thanks to its size and positioning, which give it a mechanical advantage, or “moment arm.” This means it can do its job efficiently with minimal effort.

The thing is, posture matters.

If someone has an anterior pelvic tilt (picture the pelvis tipping forward), the gluteus medius can shift from being an abductor to an internal rotator of the hip.

This internal rotation is often linked with PFP, and it tells us that poor posture isn’t just a cosmetic issue—it changes how the muscles function.

Posture

Posture is important in how we move and, ultimately, how our bodies distribute forces during walking, running, or climbing stairs.

In PFP patients, common postures like sway back or excessive lumbar lordosis can exacerbate symptoms.

- Sway back posture: The pelvis and hips move forward, creating a hinge-like effect in the lower back. This shifts the body’s weight distribution and forces the knee joint into awkward, stressful positions.

- Excessive lumbar lordosis: The pelvis tips forward (anterior pelvic tilt), increasing the curve of the lower back. This not only affects hip alignment but also creates inefficiencies in muscle activation during movement.

These postures create compensatory movement patterns that overload the PFJ.

For example, a patient might use their tensor fascia latae more than their gluteus medius during hip abduction, and given the fibres of the TFL terminate into the ITB, this movement may result in increased load being applied to the lateral patella

Why Alignment Is Important In Rehab

So, what’s the takeaway for rehabilitation?

Strengthening exercises alone aren’t enough. Sure, weak muscles are part of the problem, but alignment—how a patient’s skeleton and muscles work together in motion—is equally important.

Traditional strength tests, done at a single joint angle, might not show the full picture. A person could show good strength in one position, but slight shifts in posture during movement can reveal hidden weaknesses or compensations.

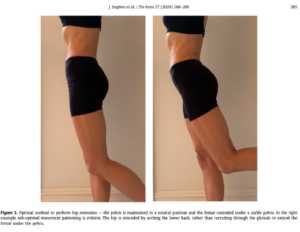

For instance, someone with a lordotic posture might arch their lower back instead of extending their hip when asked to do so. This compensation bypasses the glutes and puts extra strain on the spine.

A study explored this idea by focusing on alignment during rehabilitation for PFP patients who had previously failed traditional physiotherapy.

The researchers assessed

- Posture

- Alignment

- Dynamic movement patterns

In a group of patients with chronic PFP. The results showed that many patients had postural deviations that influenced how their muscles functioned.

Simple Evaluation

The body is designed to have specific muscles perform specific tasks, decreasing strain on bones and joints.

When muscles are used inefficiently it creates unnecessary stress. Strengthening alone doesn’t fix this. For example, you might make a muscle stronger, but if the movement pattern is flawed, the stress on your patellofemoral joint remains.

That’s why we assess movement in progressive steps.

Start with simple, pain-free positions to evaluate and improve mechanics.

For example, hip extension might be tested in a lying position first, then standing, and eventually during more “challenging” tasks like climbing stairs. Only when movement patterns are optimised do we assess strength deficits.

This layered approach ensures we’re treating the root cause, not just the symptoms.

Forces Acting On The PFJ

Let’s consider the PFJ itself. Rather than focusing on the joint as the problem, it’s more effective to look at the forces acting upon it.

Imagine a seesaw: the PFJ is at the pivot point, influenced by forces from surrounding muscles and bones. By improving the way these forces interact—through better posture, alignment, and muscle coordination—you reduce strain on the PFJ itself.

A significant aspect of this is lumbo-pelvic dissociation, which helps patients separate movements of the hip, pelvis, and lumbar spine.

Postures like anterior pelvic tilt or forward pelvic sway disrupt this balance, increasing strain on the lower limb. While these interventions may not yet have robust scientific evidence due to measurement challenges, clinicians see real-world improvements in patients.

Starting With The Basics In Mind

Rehab begins by addressing muscle tightness with a flexibility program. (if there is any infexability)

From there, the focus shifts to movement correction, starting at the hip and working downward to the foot and ankle. This proximal-to-distal approach is important because the alignment and mechanics of proximal structures heavily influence distal movement patterns.

Think of it like a chain: if the top link is out of alignment, the rest will follow suit.

Initial exercises should emphasise simple, single-plane movements like hip extension and abduction.

These movements may seem basic, but performing them correctly lays the foundation for more complex task.

Once the person master isolated movements, we can then challenge them with multi-joint exercises like stair climbing, squats, and lunges.

These movements demand greater control and coordination because they involve simultaneous joint actions.

The strip down of movements to their isolated chunks helps to prevent overload and ensure readiness for real-world activities.

In one study 85% of patients experience significant pain relief with this approach.

However, challenges persist. Some people experience symptom recurrence when they stop their exercises, which highlights the need for education.

Additionally, anatomical factors like femoral anteversion can complicate rehabilitation. For instance, patients with this condition often struggle to sense activation in their gluteal muscles during exercises, affecting their outcomes.

Psychological factors also contribute to PFP. Chronic pain is rarely just physical; it’s influenced by mental and emotional dimensions. Addressing these aspects can improve treatment outcomes, adding another layer of complexity to rehabilitation.

Clinical Tips

Checking for compensations:

Observing how patients perform tasks like hip abduction or extension can show whether they’re compensating with other muscles or positioning their joints in awkward angles.

For example, excessive hip flexion during abduction might signal that the TFL is overcompensating for weak glutes, increasing lateral patellar stress.

Control and alignment:

Focus on correcting proximal joint alignments (hip and pelvis) before progressing to the knee and ankle. Addressing issues like pelvic tilt or weakness in hip abductors to prevent compensatory patterns can help patellofemoral pain.

Good alignment reduces stress on the knee and improves muscle activation, providing a foundation for more complex movements.

Muscle awareness:

Advise patients to be aware of where they feel muscle activation during exercises to help them understand correct movement patterns.

This method helps patients to distinguish between effective and ineffective muscle engagement, allowing them to adjust their movements both in clinic and at home, leading to better muscle control and fewer compensations.

Gradual progression:

Start with simple, isolated movements (e.g., hip extension) and progress to more complex, multi-joint exercises (e.g., squats or stair climbing) as patients master basic control.

The step-by-step approach helps patients to maintain good form and reduce the risk of re-injuring the knee when introducing more challenging tasks.

Think long term:

Encourage patients to continue exercises beyond their initial rehabilitation. Use strategies like self-monitoring and follow-up sessions to maintain adherence, as stopping exercises often leads to symptom recurrence.

References:

- de Oliveira Silva, D., Briani, R.V., Pazzinatto, M.F., Ferrari, D., Aragão, F.A. and de Azevedo, F.M., 2015. Reduced knee flexion is a possible cause of increased loading rates in individuals with patellofemoral pain. Clinical Biomechanics, 30(9), pp.971-975.

- Kujala, U.M., Jaakkola, L.H., Koskinen, S.K., Taimela, S., Hurme, M. and Nelimarkka, O., 1993. Scoring of patellofemoral disorders. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery, 9(2), pp.159-163.

- Norris, C.M., 1995. Spinal stabilisation: 4. Muscle imbalance and the low back. Physiotherapy, 81(3), pp.127-138.

- Stephen, J., Ephgrave, C., Ball, S. and Church, S., 2020. Current concepts in the management of patellofemoral pain—the role of alignment. The Knee, 27(2), pp.280-286.

Leave a Reply