How Trigger points work?

Are trigger points really just the tight, painful “knots” in muscles—or is there something deeper going on? As physiotherapists, we encounter trigger points all the time, but what if the story behind them is more complex than we’ve been led to believe?

In this article, we take a deep dive into the controversial world of trigger points, using the study by Quintner and colleagues as our guiding reference. Their research challenges some long-held beliefs and gives a fresh perspective on the mechanisms behind trigger points, their biochemical environment, and their role in pain and dysfunction.

If you’ve ever questioned whether “knots” are the true cause of your patient’s pain—or just one piece of a larger puzzle—this article is for you.

This article breakings down the study by Quintner’s et al and explains what’s really happening at the biochemical and neurological levels, why trigger points may not just be a local muscle issue, and what that means for treatment. You’ll come away with a better understanding of the systemic factors at play and practical takeaways for evidence-based, patient-centered care.

Ready to challenge what you know about trigger points and take your clinical reasoning to the next level?

Let’s get into it

In A Nutshell

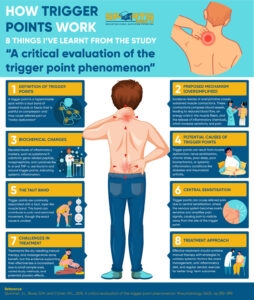

Main Takeaway:

The study points out that while treatments like dry needling and manual therapy can be helpful for trigger points, the evidence behind them isn’t very strong, mainly because of small sample sizes and varying research methods.

It also stresses the importance of considering bigger factors, like stress and poor posture, that can lead to trigger points, and suggests taking a more well-rounded approach to treatment.

Clinical Tip:

When treating trigger points, it’s important to address the underlying causes, such as poor posture or stress, in addition to using hands-on techniques, to promote long-term relief and prevent recurrence.

Aim Of The Study

In the most simples of explanation the aim of the study is to look into the underlying mechanisms of trigger points

What Is A Trigger Point?

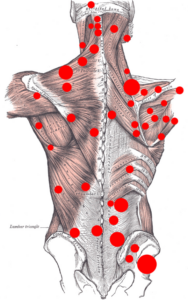

A trigger point is a hyperirritable spot within a taut band of skeletal muscle or fascia that is painful on compression and may cause referred pain, motor “dysfunction”, or autonomic symptoms.

It is often associated with myofascial pain syndrome and thought to result from localised muscle “dysfunction”, nerve sensitisation, or biochemical load distribution

Biochemical Changes In & Around “Trigger Points”

When we look at trigger points from a biochemical perspective, it’s fascinating and complex at the same time (as with most things in sports medicine – from my humble opinion 😄)

Research shows that inflammatory markers like:

- Substance P

- Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)

- Norepinephrine

- Cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α

Are elevated in and around trigger points.

However, these chemical changes aren’t confined to the affected muscles. Other areas that seem uninvolved in the pain show similar abnormalities.

This suggests that trigger points might not just be “muscle knots” but part of a bigger picture and involving systemic inflammation or altered nerve function.

In terms of physiotherapy,

A trigger point might not just be a local problem—it could be a sign of broader physiological imbalances.

Factors like:

- Chronic stress

- Poor sleep quality

- Even systemic inflammatory conditions (diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis etc) might be contributing

With this in mind, treatment shouldn’t just stop at hands-on techniques to release the “knot”.

Manual therapy should be complimented by addressing systemic issues—like discussing anti-inflammatory diet options and/or encouraging regular aerobic exercise (to name a few)

The fact that similar biochemical changes are found in uninvolved areas also raises an important question: Are trigger points the actual cause of pain, or are they symptoms of a deeper issue?

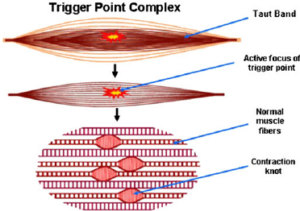

The “Taut” Muscle

The taut band is one of the key features of trigger points, often felt as a tight, rope-like structure within the muscle.

It’s usually linked to pain and limited movement. However, despite being widely discussed in the literature and the physio world the exact cause and mechanism of the “taut” band is still unclear.

One theory suggests that “taut” bands form when the neuromuscular junctions, or the areas where nerves meet muscles, malfunction.

This causes them to release too much acetylcholine, which leads to continuous muscle contractions. These contractions can compress blood vessels, resulting in reduced blood flow, which creates an energy crisis in the muscle fibers.

This process might then trigger the release of inflammatory chemicals, which increase sensitivity in the area.

However, this theory IS NOT proven.

What makes things a little more complicated and harder to understand is that these “taut” bands aren’t only seen in people with trigger points.

Research has found similar tight bands in people who don’t experience pain, with studies by Shah et al. (2005) noting taut bands in asymptomatic muscles.

Imaging like ultrasound and MRI elastography have also tried to visualise these taut bands, but the results have been inconsistent and unclear, as seen in studies by Chen & colleagues.

Current Treatments & Challenges

When it comes to treating trigger points, the range of options is extensive.

- Dry needling

- Manual compression

- Massage

- Even botulinum toxin injections.

However, the research backing these treatments is surprisingly limited.

While many patients report finding relief, systematic reviews and meta-analyses point out significant flaws in the evidence (small sample sizes, inconsistent diagnostic criteria, and the potential influence of the placebo effect)

*Side Note*

Now, I always say, if it works, it works. Theres no need to scavenge for research to support a specific hypothesis and seek justification to use specific modalities.

At the end of the day if the patient feels better, whether is backed fully by science or not, then it doesn’t really matter (as long as there’s no adverse effects after words)

Now, back to the science,

One of the main issues in research studies is that treatments are often combined.

For example, dry needling is usually done alongside manual therapy, patient education, or stretching, making it difficult to pinpoint which component of the treatment is actually effective.

Additionally, trigger points may not be the only source of a patient’s pain—other factors such as stress, poor sleep, and “faulty” biomechanics can contribute, making it harder to isolate the impact of just one treatment.

In terms of physio,

This doesn’t mean abandoning these methods altogether, but it does suggest taking a more critical and tailored approach.

Instead of relying on a one-size-fits-all solution, try integrating multiple strategies. For instance, combining manual therapy with exercises and patient education can address both immediate pain and the underlying causes.

It’s also important to set realistic expectations for your patients. While a particular treatment might give short-term relief, lasting improvement typically requires a more thought out strategy.

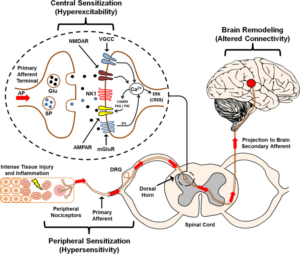

Referred Pain & Central Sensitisation

One of the most fascinating features of trigger points is their ability to cause referred pain (discomfort is felt in a different area from the actual trigger point)

We all know it, pain science is one complicated area of medicine.

Research show that referred pain could be tied to central sensitisation, a condition where the nervous system becomes overly sensitive, intensifying pain signals and spreading them to other areas.

In the context of the “taut” muscle, central sensitisation also means that just treating the trigger point may not fully resolve the patient’s symptoms.

Incorporating techniques to calm the nervous system, like graded exposure to movement, mindfulness, or educating the patient about pain neuroscience, can be helpful.

These methods work to “retrain” the brain’s perception of pain, reducing hypersensitivity and helping the body heal.

This all ties back to the importance of clear communication with your patients.

Help them understand that their pain may not come from where they feel it and that treating the source could involve addressing areas they didn’t expect.

Evidence-Based Practice

The world of trigger point treatment is filled with debate, conflicting ideas, and research that doesn’t always provide clear answers.

As mention previously, while many clinicians find success with treatments like dry needling or massage, systematic reviews often show that the evidence supporting these methods is weak or inconclusive.

Evidence-based practice means using the most current research, along with your professional experience, to choose the most effective treatments tailored to your patients’ needs.

Even if a treatment has limited scientific backing but is effective for a particular patient, it may still be worthwhile to use, as long as you’re open about its limitations and combine it with other techniques (such as movement specific treatment).

A big part of evidence-based practice is maintaining a critical mindset.

Here are a few things I’ve learned over the years and something I would recommend to you to think about

Don’t simply accept every new trend or technique without questioning it. You should ask yourself:

- “Is the study well-designed?

- Does it apply to my patient group?

- Could there be other reasons for the results?”

By asking these questions, you can cut through the confusion and focus on what truly helps your patients.

Another key element of evidence-based practice is lifelong learning (you’re already on the right track by being here 🎉 ).

Research and our understanding of trigger points (and to be honest most things in sports medicine) are constantly evolving, so it’s important to stay curious.

Clinical Tips

Combination of treatments – Evidence suggests that standalone treatments like dry needling or compression can have benefits

However, when combined with manual therapy, home exercises, and stretching, the outcomes tend to improve as the treatment targets multiple factors contributing to pain.

Consider referred pain mechanisms – Trigger points are closely linked to central sensitisation and nerve “irritation”, which can cause pain and tenderness to radiate beyond the local muscle area.

This means that the true source of pain may not be confined to the trigger point itself. Education of the pain mechanism and being open about the treatment plan and what it aims to achieve can help with adherence and overall success

Activity modification – Encourage patients to pace their activities by gradually increasing the intensity and duration of exercise or movement, particularly when they are returning to sport after a flare-up.

This helps prevent overexertion, which can aggravate trigger points and lead to a cycle of pain and muscle tension.

References:

- Chen, Q., Bensamoun, S., Basford, J.R., Thompson, J.M. and An, K.N., 2007. Identification and quantification of myofascial taut bands with magnetic resonance elastography. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 88(12), pp.1658-1661.

- Giamberardino, M.A., Affaitati, G., Fabrizio, A. and Costantini, R., 2011. Effects of treatment of myofascial trigger points on the pain of fibromyalgia. Current pain and headache reports, 15, pp.393-399.

- Quintner, J.L., Bove, G.M. and Cohen, M.L., 2015. A critical evaluation of the trigger point phenomenon. Rheumatology, 54(3), pp.392-399.

- Shah, J.P., Danoff, J.V., Desai, M.J., Parikh, S., Nakamura, L.Y., Phillips, T.M. and Gerber, L.H., 2008. Biochemicals associated with pain and inflammation are elevated in sites near to and remote from active myofascial trigger points. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 89(1), pp.16-23.

- Shah, J.P., Phillips, T.M., Danoff, J.V. and Gerber, L.H., 2005. An in vivo microanalytical technique for measuring the local biochemical milieu of human skeletal muscle. Journal of applied physiology, 99(5), pp.1977-1984.

Leave a Reply