Patellofemoral Pain: Everything There Is To Know

Let’s dive into one of the most common (and tricky!) knee problems out there: Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFP).

If you’ve ever seen people with knee pain that appears during running, squatting, or climbing stairs, chances are you’ve run into PFP. This condition is especially common in the young & active—particularly females—and it can be a real challenge to pin down the exact cause and the best treatment for it

In this article, we’ll discuss the ins and outs, covering everything from mechanism of injury and risk factors to how it typically presents in patients. We’ll walk through the different ways to assess and diagnose it, as well as dive into evidence-based treatments that can help manage symptoms and support recovery.

We’ll even look at surgical options (for those more stubborn cases) and talk about the criteria for safely getting patients back to their sport or activity.

This is your full guide to understanding and addressing PFP. The overview is packed with practical tips and examples for you to takeaway and use in your practice.

So, let’s unpack the complexity of Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome!

What is Patellofemoral Pain syndrome?

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) is a musculoskeletal issue that causes pain in the front of the knee, or more specifically around the kneecap. The discomfort tends to worsen during weight-bearing movements that involve knee flexion.

For example,

- Squatting

- Stair climbing

- Running

- Hopping

- Jumping

Additionally, you would also hear the person complain about crepitus or grinding sensations during knee flexion, tenderness when palpating the patellar borders, minor effusion, and pain during prolonged sitting, rising from a seated position, or straightening the knee post-sitting

Did You Happen to Know?

- Full diagnosis and treatment of PFP is challenging as the knee can be highly reactive and thus cause flare up.

- A 2013 study linked patellofemoral pain syndrome to decreased quality of life in athletes. It’s common in young athletes who do a lot of jumping, cutting, and pivoting sports.

- Up to 40%of knee-related clinical visits are attributed to patellofemoral pain

- PFP accounts for a significant portion of knee injuries, particularly in females. It’s very common in basketball, volleyball & running affecting 13-26% of female athletes.

- Incidence is higher in young women compared to males.

- Patellofemoral pain can limit physical activities and contribute to long-term patellofemoral osteoarthritis

Anatomy of The Knee

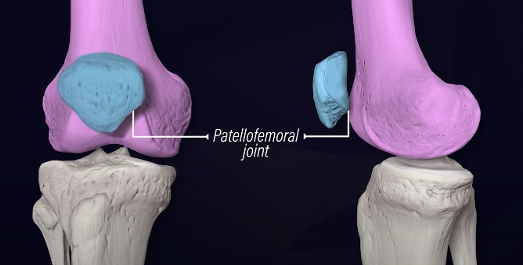

Bones:

The knee joint is primarily formed by three bones:

- Femur:The upper thigh bone.

- Tibia:The larger of the two lower leg bones (fibular) and the main weight-bearing bone.

- Patella:The kneecap, a small, flat bone that sits in front of the knee joint.

Ligaments:

Ligaments are tough, fibrous tissues that connect bone to bone and provide stability to the joint. In the knee, there are four main ligaments:

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL):Prevents the tibia from moving too far forward with the femur.

- Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL): Prevents the tibia from moving too far backward in relation to the femur.

- Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL):Provides stability to the inner part of the knee.

- Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL):Provides stability to the outer part of the knee.

Meniscus:

The menisci are two wedge-shaped pieces of cartilage (fibrocartilage) that act as shock absorbers and provide cushioning between the femur and tibia. They also help distribute the load evenly across the joint.

Muscles:

Several muscles surround and support the knee joint, including the quadriceps (front thigh muscles) and the hamstrings (back thigh muscles). They help stabilise the knee joint

The Cause of Patellofemoral Pain

The causes of PFP are complex and involve three main factors.

- Malalignment, where the kneecap doesn’t move along the groove of the femur as well as it should

- Muscular imbalances, which occur when certain muscles around the knee are either too tight or too weak, affecting joint stability

- Overactivity, often from repetitive movements like running or jumping, that places additional strain on the knee joint.

This combination of factors makes PFP a challenging condition to manage, requiring a sensible approach to treatment and prevention.

Let’s explore them in more detail

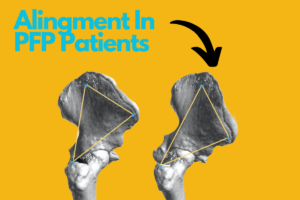

Malalignment

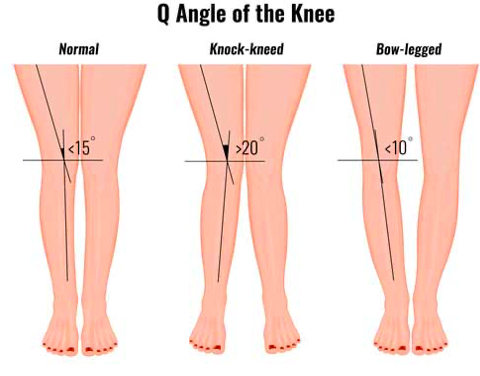

A common cause of patellofemoral pain involves several structural elements in the knee. This essentially boils down to an increased Q-angle when weight-bearing (which affects the line of pull of the quadriceps)

For example:

- Genu valgum (knock-knees)

- Tibia varum (bow-leggedness)

Both of these anatomical varients can place different stresses on the knee,

influencing the development of PFP.

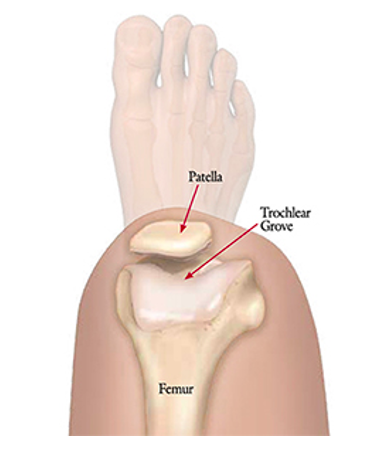

The stability of the patella depends on the alignment of the femur and tibia, the structural characteristics of the patellofemoral joint, and the surrounding soft tissue constraints.

A big part of this setup is the trochlear groove — a “path” in the femur that guides patellar movement. When there is a shallowness or underdevelopment of this groove, (trochlear groove hypoplasia) patellar stability is often compromised.

The instability can lead to discomfort around the kneecap (the main complaint in PFP) and even potentially the development of chondromalacia patellae, where the cartilage under the kneecap starts to soften and deteriorate.

Muscular Imbalance

Muscular strength and range of motion, particularly within the quadriceps, are key contributors to the development of patellofemoral pain. The reduction in muscle bulk and output is a common observation, with the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) often being particularly affected.

Research has shown that in many cases, the VMO has less volume and strength compared to the unaffected side. Additionally, delayed activation of the VMO relative to the vastus lateralis has been noted, which can contribute to poor patellar tracking.

That being said, there is no need to isolate the VMO per se. Working on knee extension activation via functional and specific exercises is always going to be the most sensible approach.

However, it’s not just the quadriceps that matter; trunk and hip biomechanics are also essential to patellofemoral tracking. Weakness in eccentric hip abduction and external rotation can lead to increased hip adduction and internal rotation during movement, placing additional strain on the knee joint.

This dynamic weakness can force the quadriceps to work harder to stabilise the knee, raising compression in the patellofemoral joint and worsening patellar maltracking. Over time, this added stress can even accelerate the development of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis.

Overactivity

Muscle weakness and patellar tracking aside, patellofemoral pain often comes down to one core issue: too much load and not enough rest.

It’s a common problem among young, active people, especially in sports or fitness environments where training volume ramps up quickly. When activity levels spike—whether it’s athletes pushing their conditioning or adults tackling intense training programs like military training—PFP risk increases.

In fact, a study on infantry recruits found that PFP cases rose significantly as they progressed through standard training routines. The study highlights that gradual load progression and rest time are essential in preventing PFP, especially when training volume gets intense.

The Epidemiology of PFP

Incidence and Prevalence:

Precisely pinpointing its annual occurrence (incidence) and the overall prevalence is a challenge.

Why?

It can affect a wide spectrum of people. From active children to sedentary elderly adults, patellofemoral pain does not discriminate by age.

However, there’s a notable surge in the prevalence among a specific group:

Young, active adolescents between the ages of 12 and 18.

They often present in outpatient clinics with complaints of chronic anterior knee pain, which is typically associated with sports.

Moreover, it’s important to highlight that PFP also has a significant presence among active adults, often humorously referred to as “weekend warriors,” as well as young military recruits.

All of these groups have something in common – being very active.

Gender Differences:

Interestingly, research shows that patellofemoral pain seems to be more common among women than men. Epidemiological studies point to a significant gender gap, with women potentially being twice as likely to experience PFP each year compared to men.

For example, one study with military recruits found that female participants had an incidence rate of 33 cases per 1,000 person-years, while males had only 15 cases per 1,000 person-years, making women about 2.23 times more likely to develop PFP.

This trend may relate to differences in anatomy, biomechanics, or even activity types, but the exact reasons are still a hot topic in research.

Get the ACL assessment & rehab guide with over 50+ exercises to help you structure your rehab programme

I’ve spent over 1,000 hours studying sports medicine to give you the best tips and tools to succeed with your patients

Now, I’ve put everything I know about ACL’s into a simple guide… for free.

Symptoms & Clinical Presentation

Patients with Patellofemoral Pain commonly report the following:

- Symptoms tend to worsen during specific activities such as climbing stairs, descending stairs, squatting, running, or prolonged sitting.

- PFP is described by diffused, localised discomfort centred around or behind the patella. The pain is often experienced during the activities mentioned above.

- When asked to indicate the location of pain, patients show the area by placing their hands over the front of the knee or drawing a circular motion with their fingers around the patella, a gesture referred to as the “circle sign.”

Onset and Nature of Symptoms:

- Typically, symptoms develop gradually over time, although in some cases, they may suddenly appear due to trauma or injury.

- Patients frequently describe the pain as an ache, though it may also be described as sharp, dependent on severity. This pain can be unilateral (affecting one knee) or bilateral (affecting both knees).

Additional Symptoms:

- Stiffness: Some patients may report stiffness or discomfort during prolonged sitting with the knees bent. This is referred to as the “theater” or “moviegoer” sign.

- Sensations of Instability: Patients occasionally mention a sensation of the knee giving way or buckling. This sensation may result from the pain’s inhibitory effect on the quadriceps muscle contraction. However, it should be distinguished from instability arising from patellar dislocation, subluxation, or ligamentous knee injuries.

- Popping or Catching Sensations: Some people may describe feelings of popping or catching within the knee. Importantly, joint locking is not a typical feature of PFP, and it often implies the presence of a meniscal tear or a loose body within the joint.

- Swelling: While mild swelling may occasionally occur, it is uncommon to observe significant joint effusion.

Mechanism of Injury

Patellofemoral pain is complex and thus various biomechanical, behavioural (overuse) and anatomical factors contribute to its development.

It is predominantly thought of as an overuse injury, meaning that an increase in frequency, intensity and/or duration of exercise without adequate rest or preparation period is the driver of developing PFP.

In terms of origins, PFP is influenced by various biomechanical factors. These conditions often occur during activities involving abrupt movements, landing, or deceleration in sports.

Weiss et al (2015) Studies has identified several biomechanical variables contributing to PFP. The most significant factors involve the frontal plane mechanics of the knee.

Excessive knee abduction loading and shallow knee flexion angles are common. During dynamic knee abduction, the ligaments and other knee structures are strained, primarily due to poor control of the hip musculature, leading to increased forces on the knee, and thus the patellofemoral joint.

These abnormal frontal plane mechanics can disrupt normal knee joint function, increasing the risk of PFP. Furthermore, inadequate hip control, including increased hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation, affects knee stability and contributes to knee valgus (abduction). These hip mechanics may affect patellofemoral joint positioning and increase patellofemoral contact stress, leading to pain.

Ankle biomechanics, specifically reduced plantar flexion, is also a contributor, as decreased ankle joint function can transfer excessive forces to the knee, potentially increasing injury risk.

Patellofemoral pain occurs due to a combination of factors that involve the knee, hip, and ankle. Insufficient control, particularly in the frontal plane, muscle fatigue and altered knee and hip mechanics increase stress on the knee structures, ultimately contributing to the development of PFP.

Will Patellofemoral Pain Ever Go Away? – The Clinical Course

Long-Term Outcome:

Contrary to previous beliefs, research now show that patellofemoral pain is not a minor and self-limiting condition. Instead, it is a stubborn ailment that can persist for many years and has the potential to contribute to the development of long-term patellofemoral osteoarthritis. This risk is especially significant in cases where PFP begins in adolescence.

Predictors of Poor Outcomes:

The severity of pain and the duration of symptoms are key indicators of a poor prognosis. In other words, if the pain is more intense, or if the symptoms persist for a longer time, it’s less likely that the patient will have a positive outcome.

Unfavourable Recovery Rates:

A significant portion of people dealing with PFP may not see a favourable recovery even with various interventions. This means that the condition doesn’t always respond well to treatment, and outcomes can be disappointing for many people, even when adhering to rehab for 12 months.

Duration and Pain Scale Score as Predictors:

One of the most consistent indicators of a poor long-term prognosis in PFP is the duration of the condition. If a person has been suffering from PFP for more than two months, it’s often a sign that their prognosis isn’t very optimistic.

Additionally, a score of less than 70 on the anterior knee pain scale is also associated with poor long-term outcomes.

The Role of Imaging

The diagnosis of PFP is primarily based on clinical evaluation, and imaging is often unnecessary.

However, radiography may be needed in specific situations, such as recent trauma, older patients (above 50) to check for patellofemoral osteoarthritis, skeletal immaturity, suspected bipartite patella, loose bodies, or when conservative treatment don’t show improvement.

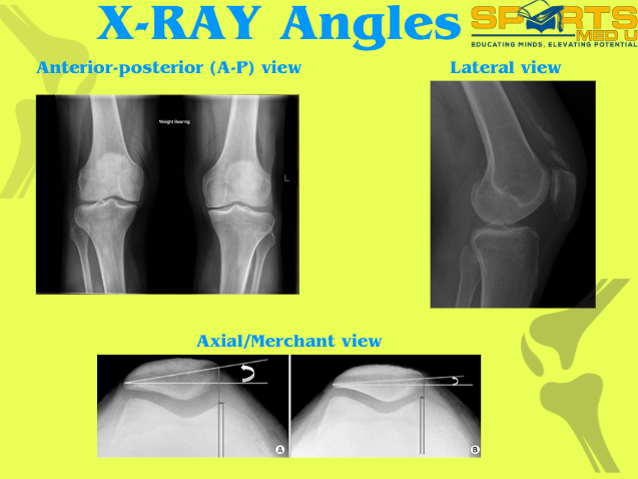

Radiography:

Radiography, like X-rays, complements clinical assessment but may not always correlate with symptoms. It’s important in cases with no improvement after conservative treatment, severe malalignment, or recent trauma.

The radiographic views include weight-bearing anterior-posterior (A-P), lateral, and axial/Merchant views, with each offering a new perspective and angle of the joint.

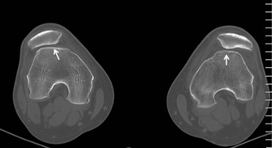

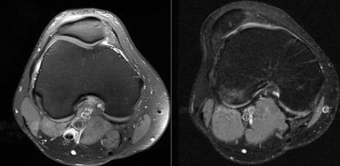

Advanced Imaging Techniques:

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are generally unnecessary for most PFPS cases. MRI is best for evaluating issues like malalignment, trochlear dysplasia, patella tilt, and chondral injuries.

It’s also useful for detecting loose bodies, stress fractures, and bone marrow changes indicating patellar subluxation or dislocation. MRI is particularly effective for assessing patellofemoral osteoarthritis, which manifests as cartilage loss, subchondral changes, edema, and cysts on imaging.

Surgery Options for PFP

It’s typically considered a last resort for patellar femoral pain, only considered when nonoperative treatments fail to bring relief after 6 to 12 months. Surgery is warranted when there is a clear and specific problem that can be addressed surgically, such as an identifiable lesion or patellofemoral imbalance.

There are three general surgical options: realignment, resurfacing, and arthroplasty.

Realignment Procedures:

- Lateral Release:This minimally invasive procedure addresses a tight lateral retinaculum and lateral patellar tilt. Early knee range of motion is very important to prevent postoperative stiffness.

- Medial Tibial Tubercle Transfer:This procedure can be successful in treating PFP, decreasing patellar load, and reducing postoperative stiffness. Full weight-bearing should be avoided for six weeks to allow for healing.

Resurfacing Procedures:

Procedures like autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI-C) or osteochondral transfers have mixed success in treating PFP, particularly when there’s cartilage damage in the patellofemoral joint.

Patellofemoral Arthroplasty:

Reserved for severe cases of osteoarthritic degeneration and may enable a return to some sports with limitations.

Effectiveness:

Surgery for PFP is challenging to assess due to limited controlled studies. However, many studies show that surgery doesn’t significantly improve outcomes compared to conservative treatments.

As mentioned, surgery is usually the last option for PFP and may not be entirely effective. It’s generally considered for cases unresponsive to conservative treatment.

In selected cases with specific issues like severe malalignment, patella alta, or lateral patellar compression syndrome, surgery can have good results. However, it’s important to be cautious as failure rates have been reported in a significant percentage of cases.

Risk Factors for Developing Patellofemoral Pain

Many studies have explored various factors that can increase the risk of developing patellofemoral pain. Prospective research has primarily focused on intrinsic factors, such as anatomic, neuromuscular, and movement-related issues, as these can be modified through rehabilitation to prevent the condition.

Variables like:

- Height

- Body mass

- Body mass index

- Body fat percentage

- Age

- Somatotype (Somatotype is the skeletal frame and body composition that an individual is said to be born with)

Have been examined but aren’t significant risk factors for the development of PFP.

Anatomic Factors and Soft Tissue Restrictions:

Strong correlations have been found between anatomic factors (like soft tissue restrictions) and a higher risk of patellofemoral pain.

For instance, tightness in quadriceps, hamstrings, triceps surae, and the iliotibial band has been linked to alterations in joint movement, which can increase stress on the patellofemoral joint.

Lower Extremity Positioning:

Issues, like increased navicular drop and tibial torsion can also increase lateral patellofemoral joint stress due to an altered anatomical leg alignment

Neuromuscular Function:

People with patellofemoral pain often show neuromuscular issues, including muscle weakness in knee extensors, knee flexors, and hip abductors. Weak knee extensors can predict future patellofemoral pain and may lead to increased stress on the joint due to altered hip movement.

Glute Weakness Controversy:

There’s debate about whether glute weakness is a cause or a symptom of patellofemoral pain. Either way, it’s a good place to start when objectively assessing.

A useful tool to measure strength is a hand held dynanometer

Biomechanics during Jump-Landing:

Studies have identified specific risk factors during functional activities like jump-landing tasks. For example, greater knee abduction moments during landing can increase the risk of developing patellofemoral pain, particularly in adolescent females

Subjective Assessment

Assessing patellofemoral pain starts with a thorough subjective examination, discussing not only what the person was doing before symptoms started but also what makes their pain better or worse.

Since PFP is often due to overuse, recent changes in activity levels (training, running, hiking etc.) are the first factors to consider. Maybe they’ve increased their frequency, duration, or intensity, or perhaps taken on high-impact activities like hill runs.

Mistakes such as ramping up intensity too quickly, skipping rest days, or introducing strenuous conditioning are common contributors to PFP development.

Additionally, factors such as:

- The use of inappropriate or excessively worn footwear

- Recent heavy resistance training (especially heavy and continuous deep knee flexion exercises like squats and lunges)

- Running on altered surfaces or hills.

Must be considered and education given on their impact on knee health if mentioned by the patient.

PFP can also present as an acute re-exacerbation of a chronic condition.

Traumatic knee injuries, patellar subluxation, dislocation, or surgeries should also be noted, as they may directly irritate the articular cartilage or change forces across the patellofemoral joint, leading to PFP.

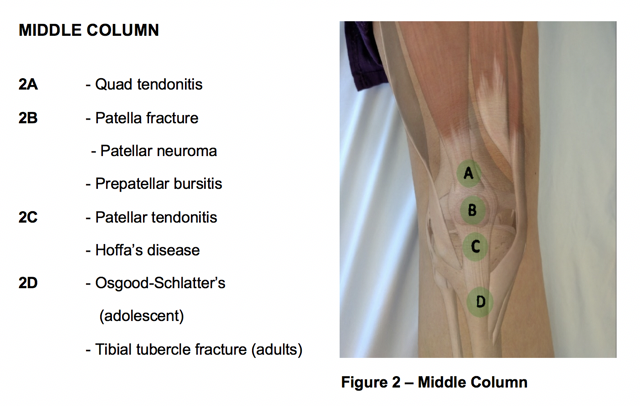

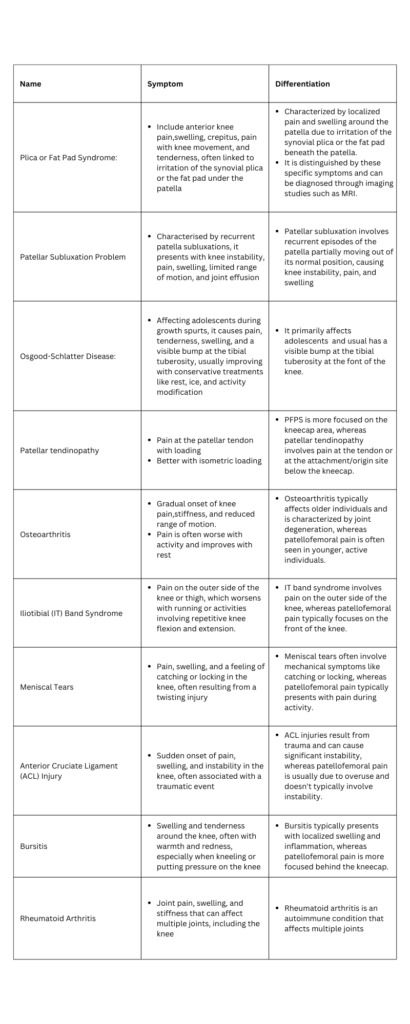

Importantly, the assessment should rule out other possible sources of pain that mimic PFP, like intra-articular issues, plica syndromes, Osgood-Schlatter disease, and neuromas.

Objective Assessment

Whilst you can diagnose PFP with a subjective assessment alone, objective test can help cement the diagnosis and pinpoint areas to work on during rehab.

However, an important note to make is that there is no definitive clinical test to diagnose PFP. Various tests have been proposed, but all lack sensitivity (bad at pinpointing the specific structure involved).

This makes PFP a diagnosis of exclusion, often identified after ruling out other knee conditions, such as tibiofemoral osteoarthritis, plica syndrome, or patella tendinopathy.

Tests for PFP Diagnosis

Squat:

According to the recent consensus statement from the Fourth International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, anterior knee pain experienced during a squatting is the best available test, and patellofemoral pain is seen in 80% of people who are positive on this test

Vastus Medialis Coordination Test:

This test evaluates coordination during knee extension and can indicate limitations in vastus medialis muscle coordination

Description: While the patient lies supine, the examiner positions their fist beneath the patient’s knee, instructing them to slowly extend their knee without exerting pressure or lifting away from the examiner’s hand.

Full extension should be achieved.

A positive test shows a lack of coordinated full extension. The patient faces difficulty in achieving smooth extension and may rely on hip extensors or flexors for the extension (poor muscle control)

Patellar Apprehension Test:

The lateral patellar glide, this test is used to reproduce patient pain or apprehension.

Description: The patellar apprehension test, sometimes called the Fairbanks apprehension test, is done with the patient lying supine and relaxed. During this test, the examiner gently pushes the patient’s patella laterally (outward) to create a lateral patellar glide. Starting with the knee flexed at 30°, the examiner holds the leg at the ankle/heel with one hand and performs a gradual flexion in the knee and hip while maintaining the lateral glide .

A positive test is observed when the test reproduces the patient’s pain or apprehension

Eccentric Step Test:

In this test, patients step down from a platform to assess knee pain during eccentric control.

Description: Patients perform the assessment without footwear. The step’s height is typically set at 15 cm or approximately 50% of the tibia’s length

During the test, the patient is instructed to stand on the step, place their hands on their hips, and gently step down as slowly and smoothly as possible. The patient should maintain their hands on their hips throughout the test. After completing the test with one leg, it is repeated with the other leg without any warm-up or practice attempts.

A positive result is when the patient experiences knee pain during the test.

Single Leg Squat:

This test assesses dynamic hip and quadriceps strength and can show compensatory movements.

Description: The single-leg squat assesses dynamic hip and quadriceps strength. It places greater mechanical demands compared to a double leg squat and can show compensatory movements like knee valgus.

Patients with PFP, in comparison to controls, show increased ipsilateral (same side) trunk lean, contralateral (opposite side) pelvic drop, hip adduction, and knee abduction when performing a single-leg squat.

Tenderness & Palpation:

Tenderness on palpation of the patellar edges is a test with limited evidence as PFP is evident in 71%–75% of people with this tenderness.

It should not be used to rule in or rule out patellofemoral pain as it’s a common complaint for many knee issues around the front of the knee.

Get the ACL assessment & rehab guide with over 50+ exercises to help you structure your rehab programme

I’ve spent over 1,000 hours studying sports medicine to give you the best tips and tools to succeed with your patients

Now, I’ve put everything I know about ACL’s into a simple guide… for free.

Early Management

Patellofemoral pain is a complex issue that not only affects a large number of people but also tends to become chronic if not managed effectively. The persistent pain around the front of the knee can significantly impact daily life and performance in sport. Hence, timely and sensible rehab is important to nail down to prevent long-term consequences.

That being said, treatment planning for PFP is challenging due to the absence of standardised treatment guidelines. Although sports medicine experts recommend a range of management strategies, from strengthening and movement retraining to load management, the lack of a universal protocol shows the complexity of PFP.

Each case often requires a tailored approach, addressing the unique factors that drive the persons symptoms.

Personalised Treatment:

To manage patellofemoral pain effectively, practitioners need a systematic approach that addresses various risk factors spanning across the lower half of the body.

Localised knee issues, such as joint mobility and strength deficits, are important, but factors above the knee, like hip and trunk control, and factors below the knee such as the foot and ankle function, are equally vital in influencing knee positioning and function.

Starting with the “low-hanging fruit,” such as restoring the range of motion and correcting biomechanical patterns, can often make a big difference. For instance, addressing knee valgus or uneven weight distribution during functional tasks, such as squatting or stepping, can lay the foundation for better movement quality and set the stage for more advanced rehabilitation in the later stages.

Patient Education:

Patient education is a cornerstone in managing patellofemoral pain. It helps in two ways:

- Supports understanding

- Supports adherence to the rehabilitation plan.

By explaining the condition, expected progression, and the reasons behind each aspect of treatment, clinicians can help patients develop realistic expectations and appreciate the importance of consistency.

Highlighting the potential consequences of non-adherence can further motivate patients to stay engaged with their recovery. Providing resources like informative leaflets can also be beneficial, as it offers a reference to reinforce what they’ve learned, empowering them to take an active role in managing their condition.

Activity Modification:

For athletes with patellofemoral pain, balancing relative rest with activity modification is the most important aspect of their recovery. Overuse often underlies PFP, thus easing up on high-impact movements or heavy training loads will have a positive impact, especially in acute cases. The rest allows affected tissues to heal and symptoms to ease.

However, chronic PFP is a unique challenge. Daily activities that increase joint loading can continuously aggravate the pain. This is where patient education becomes the number one priority. Guiding people on how to adjust their routines and avoid excessive knee stress helps them manage pain effectively on their own while staying as active as possible.

Other Treatments to Consider

Foot Orthosis:

The role of foot orthoses in treating patellofemoral pain is still widely debated, with mixed evidence on their effectiveness. A recent consensus suggests that foot orthoses may offer short-term pain relief, though their impact seems most beneficial when combined with physiotherapy. A systematic review also found limited evidence for prefabricated foot orthosis, with better results observed when combined with physiotherapy.

That being said, responses to foot orthoses can vary significantly from person to person, with factors like midfoot mobility and ankle dorsiflexion often influencing success. As with most things in MSK, there’s no size that fits all. Instead, treatment should be tailored to each patient’s unique clinical presentation rather than applying a universal approach based solely on the diagnosis.

Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation:

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) uses electrical impulses to trigger muscle contractions, and some advocate for its use as part of a cost-effective, home-based therapy for conditions like patellofemoral pain. While NMES can support muscle activation, especially in cases where voluntary contraction is limited, studies show that it’s not more effective than supervised physical therapy when used on its own.

For best results, NMES should complement an active rehabilitation program rather than replace it.

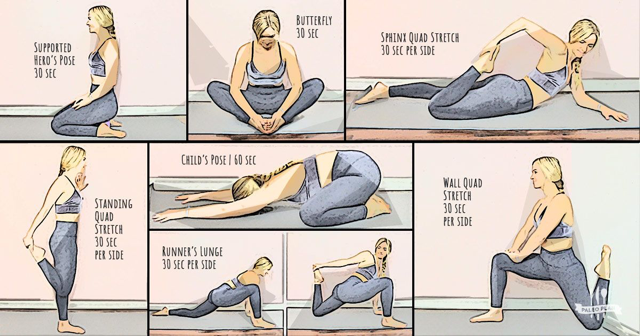

Stretching:

Stretching various muscle groups, including the hamstrings, quadriceps, iliopsoas, gastrocnemius, and iliotibial band, has been explored for PFP. It’s theorised that tightness in these muscle groups may affect patellofemoral joint forces.

Stretching, either alone or combined with strengthening exercises, can decrease symptoms in up to 60% of patients. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching, like the contract-relax method, may have an advantage over traditional static stretching.

Again, keep in mind that this approach may be most beneficial for patients that have shortened muscles (determined by objective examination) and thus can be an excellent option for majority, and a time waster for a few.

Pharmacotherapy:

Simple analgesics like aspirin and NSAID’s (ibuprofen), is sometimes used for managing PFP. However, evidence for the efficacy of these medications, particularly NSAIDs, is limited.

While short courses of NSAIDs may be considered when other treatments have failed, their use is debated due to the absence of inflammation in PFP cases and concerns about potential adverse effects on muscle and tendon healing responses.

Role of Taping

Taping, proprioceptive training and shoe inserts can be most effective when used in conjunction with exercise. However, they tend to be less effective when implemented on their own.

Various taping methods are available, such as:

- McConnell taping

- Infrapatellar taping

- Kinesiotaping

- Other custom taping approaches.

McConnell tape is rigid and designed for structural support, while Kinesiology tape is more flexible and gentle, which doesn’t restrict motion.

McConnell taping aims to reposition the patella within the femoral trochlea, theoretically reducing pain associated with PFP and enhancing quadriceps and patellofemoral movements.

Several studies have shown the efficacy of patellar taping and bracing in reducing pain and improving postural and functional control. It aims to mechanically adjust the patella’s position and enhance its tracking within the trochlear groove.

Both traditional nonelastic tape and modern elastic Kinesio Tape have been used for this purpose, with varying degrees of success. However, the timing of tape application and its clinical significance remain subjects of debate.

Exercise Based Management

Physical therapy is widely accepted as the initial and effective approach to managing patellofemoral pain. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses consistently demonstrate the positive impact of exercise in reducing pain and improving function for people with PFP.

It’s also cost-effective and recommended, especially for young adults. The mode may vary, but strength exercises, such as knee extension, squats, and dynamic balance, are generally beneficial.

It’s important to focus on pain-free movements and consider both weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing exercises at specific knee flexion angles. Emphasising the quads, hip abductors, external rotators, and core stability is essential.

Areas of focus:

- Ankle proprioception and balance

- Knee

- Hip

- Abdominals/trunk/core

Exercise Recommendations

- Split squat | Hamstring bridge | Side plank | Y-balance

- Step down | Single leg RDL’s | Hip thrust | Un-even surface balance with ball catching (a little more fun)

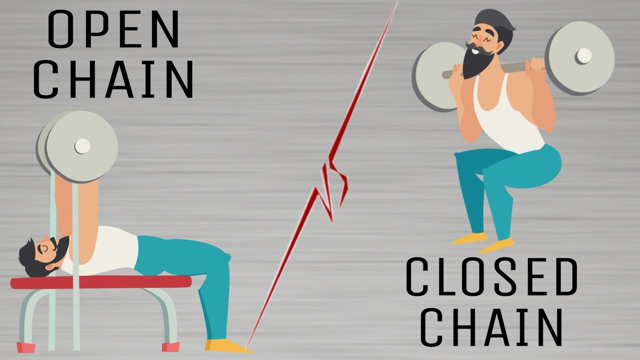

Open vs. Closed Chain Exercises:

Closed chain exercises, which mimic weight-bearing, are preferred over open chain exercises like leg extensions, which can worsen symptoms. Studies show that both open and closed chain exercises result in significant functional improvements in PFP patients.

Strengthening:

Quadriceps strengthening is essential, but hip and abdominal muscle strengthening is equally critical. Research indicates that programs targeting these muscle groups provide pain relief and improved function. Combining quadriceps strengthening with hip abductor and abdominal exercises is particularly beneficial.

Flexibility:

Tissue tightness in various muscle groups, including the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius, can contribute to patellofemoral pain. Range of motion work is recommended as a supplement to strengthening in rehab. However, it’s important to note that the effectiveness of flexibility training can vary based on the individual’s muscle tone.

Returning to Sport With PFP

Elite athletes, in particular, often face the pressure of returning to competition swiftly, especially when significant events are on the horizon. Whilst it may be unrealistic to have all these factors completely absent in the real world scenario, It’s advisable to have as many of them under control and close to ‘normal’ as possible.

Athlete checklist for sports participation clearance:

Absence of Swelling:

The injured area should show no swelling, indicating that the inflammation has subsided.

Pain-Free Movements:

The person should experience no pain when squatting or when using stairs, whether ascending or descending.

Quadriceps Strength:

Adequate quadriceps strength is essential compared to opposite side (10% difference is acceptable). You can use dynameter to measure accurately

Hamstring Flexibility:

80-degree hamstring range through straight leg raise is advisable

Normal Gait Biomechanics:

The athlete’s walking pattern should demonstrate normal biomechanics, without any noticeable limping, weight shifting or knee position

Core Stability:

Adequate core stability is important to support the body’s movements and overall stability. Whilst flawed, you can measure this objectively by asking the patient to do a plank. A good number to achieve is 2 minute hold, which indicates adequate core endurance.

Functional Tests:

Pain free or VAS score of 1/2 in challenging functional tests, such as vertical jumping, lunges, step-down exercises, single-leg presses, and balance is required.

Athlete Confidence:

Importantly, the athlete should personally feel ready and confident in the healing of their injured knee.

Get the ACL assessment & rehab guide with over 50+ exercises to help you structure your rehab programme

I’ve spent over 1,000 hours studying sports medicine to give you the best tips and tools to succeed with your patients

Now, I’ve put everything I know about ACL’s into a simple guide… for free.

Other Conditions to be Aware of

Sources

- Barton, C.J., Munteanu, S.E., Menz, H.B. and Crossley, K.M., 2010. The efficacy of foot orthoses in the treatment of individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review. Sports Medicine, 40, pp.377-395.

- de Oliveira Silva, D., Pazzinatto, M.F., Del Priore, L.B., Ferreira, A.S., Briani, R.V., Ferrari, D., Bazett-Jones, D. and de Azevedo, F.M., 2018. Knee crepitus is prevalent in women with patellofemoral pain, but is not related with function, physical activity and pain. Physical Therapy in Sport, 33, pp.7-11

- Dischiavi, S.L., Wright, A.A., Tarara, D.T. and Bleakley, C.M., 2021. Do exercises for patellofemoral pain reflect common injury mechanisms? A systematic review. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 24(3), pp.229-240.

- Farzin Halabchi, Maryam Abolhasani, Maryam Mirshahi & Zahra Alizadeh (2017) Patellofemoral pain in athletes: clinical perspectives, Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine

- Logan, C.A., Bhashyam, A.R., Tisosky, A.J., Haber, D.B., Jorgensen, A., Roy, A. and Provencher, M.T., 2017. Systematic review of the effect of taping techniques on patellofemoral pain syndrome. Sports health, 9(5), pp.456-461.

- Rothermich, M.A., Glaviano, N.R., Li, J. and Hart, J.M., 2015. Patellofemoral pain: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment options. Clinics in sports medicine, 34(2), pp.313-327.

- Weiss, K. and Whatman, C., 2015. Biomechanics associated with patellofemoral pain and ACL injuries in sports. Sports medicine, 45, pp.1325-1337.

Justas Muzikevicius

Justas is an experienced physiotherapist, author and founder of Sports MedU. From his experience as a professional athlete and now as a sports medicine expert he spends his time researching, writing and teaching clinicians how to put research into practice.

He enjoys basketball, reading and delicious food!

How Understanding The Calf Muscle Can Improve Sprint Performance

You May Also Like

Calf Strains: Everything There Is To Know

Let’s talk about a common yet often underestimated injury: calf strain. Whether the person is an a

Lateral Ankle Sprains – Everything There Is To Know

Repetitive lateral ankle sprains are more than just a nuisance—they’re a major cause of chronic

Cracking the Code of Frozen Shoulder: What You Need to Know

Imagine waking up one morning and realising you can no longer lift your arm without sharp pain or st