Lateral Ankle Sprains – Everything There Is To Know

Repetitive lateral ankle sprains are more than just a nuisance—they’re a major cause of chronic symptoms and long-term impairments, with up to 75% of cases experiencing lingering issues and a high likelihood of re-injury. Understanding lateral ankle sprains is essential for both competitive athletes and recreational weekend warriors.

In this article, we’ll cover everything there is to know about ankle sprains. From the anatomy, mechanisms of injury & clinical presentation to risk factors and imaging. We’ll also discuss practical approaches for assessment, treatment, and prevention strategies that can help reduce the chance of recurrence and improve patient outcomes.

Let’s take a closer look at lateral ankle sprains and explore effective ways to manage and prevent them.

What is a lateral ankle sprain?

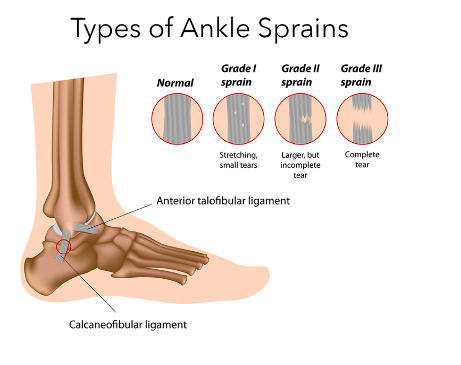

Clinically, a lateral ankle sprain occurs when there is a partial or complete tear of the ligaments on outer aspct of the ankle. It most frequently affects the anterior talofibular ligament and/or calcaneofibular ligament. Patients present with pain, swelling, and if the sprain is severe enough you may see bruising.

Did You Happen To Know?

- Repetitive lateral ankle sprains following the initial injury are very prevalent, with a high percentage (up to 75%) of cases leading to chronic symptoms.

- Due to the perceived lack of importance in society, approximately 55% of people who sustain an ankle sprain do not seek treatment.

- About 66% of cases involve an isolated injury to the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), while another 20% involve ruptures of both the ATFL and calcaneofibular ligament.

Study: Link

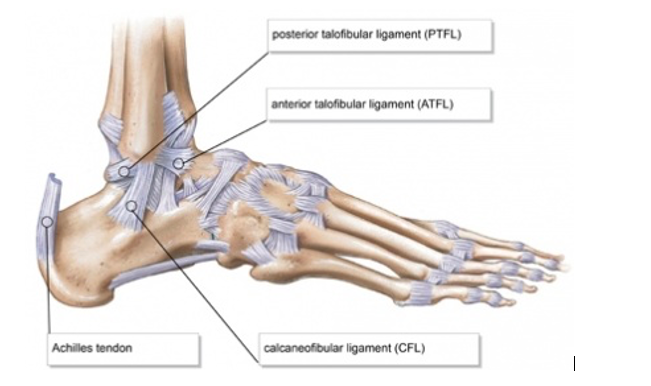

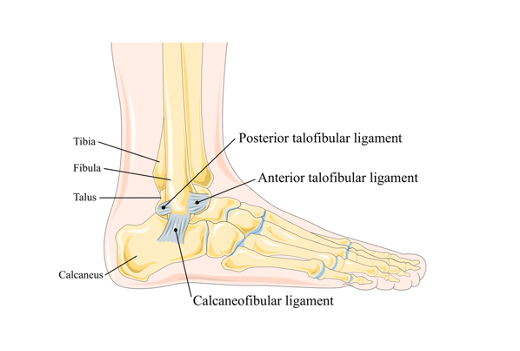

Ankle joint anatomy

The lateral aspect of the ankle is protected by three ligaments’, the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) and the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL).

Origin:

- ATFL: Originates from the anterior aspect of the lateral malleolus, which is the bony prominence on the outer side of the ankle.

- CFL: Originates from the lateral (outer) and inferior (lower) aspect of the lateral malleolus.

- PTFL: Originates from the posterior (back) aspect of the lateral malleolus

Insertion:

- ATFL: inserts onto the talus bone

- CFL: The CFL inserts onto the lateral (outer) aspect of the calcaneus bone (lateral tubercle)

- PTFL: inserts onto the posterior (back) aspect of the talus bone (posterior tubercle)

Function:

- ATFL: The ATFL is the most commonly injured ligament in the ankle. It resists excessive inversion (inward rolling) of the foot. It provides stability to the ankle joint, particularly during sports that need rapid changes in direction and sudden movements.

- CFL: It primarily resists inversion forces, preventing excessive inward rolling of the foot. The CFL also provides additional support to the ankle when the foot is in a plantarflexed (toes pointed downward) position.

- PTFL: The PTFL gives stability to the ankle by restraining excessive posterior displacement of the talus bone, preventing injuries during movements that require forceful plantarflexion.

These ligaments work together to maintain the stability and integrity of the ankle joint, preventing excessive movements that could lead to sprains or other injuries. When they all are healthy and are functioning well, they help to reduce the risk of developing ankle instability.

Get the ACL assessment & rehab guide with over 50+ exercises to help you structure your rehab programme

I’ve spent over 1,000 hours studying sports medicine to give you the best tips and tools to succeed with your patients

Now, I’ve put everything I know about ACL’s into a simple guide… for free.

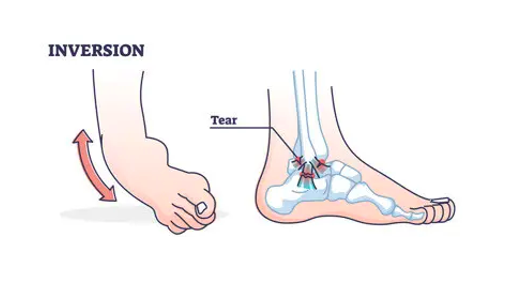

Mechanism Of Injury

Ankle sprains often occur when the foot twists forcefully inward and down—a movement known as plantar flexion and inversion. This can happen in various situations, from high-intensity sports to something as simple as awkwardly stepping off a curb.

In these cases, the lateral ligaments are affected, with the anterior talofibular ligament being the most commonly injured. If the sprain is more severe, it’s possible for the calcaneofibular ligament to sustain damage as well. In very rare instances, the posterior talofibular ligament may also be involved.

Epidemiology – Ankle Sprain Prevalence

Lateral ankle sprains are very common, especially among athletes or anyone involved in sports that require running, jumping, or quick directional changes, like basketball.

Incidence Rate: Lateral ankle sprains make up a big chunk of all ankle injuries. The exact numbers can vary depending on the activity level of the people being studied, but research shows anywhere from 2 to 35 sprains per 1,000 person-years. Bridgman et al even reported 52.7 sprains per 10,000 people.

Age and Gender: It can happen at any age, but they’re most common in young, active adults and athletes. During adolescence and early adulthood, males are more likely to experience them, most likely due to higher participation in sports.

On the flip side, in older adults, females have a higher rate of ankle sprains, which could be linked to factors like reduced muscle strength, balance issues, or the classic combination of high heels and a night out.

Sports: Lateral ankle sprains are often associated with explosive movements or just unlucky accidents. Sports like basketball, football, volleyball, and tennis—where jumping, cutting, and quick directional changes are common—see the highest rates of these injuries because of the intense demands on the ankle joint.

The Clinical Presentation of a Lateral Ankle Sprain

Patients with lateral ankle injuries commonly present with the following clinical symptoms:

- Pain is experienced on the outer aspect of the foot, specifically around the ankle joint. This pain is often exacerbated by weight-bearing.

- Swelling and bruising around the area are also frequently observed. Swelling occurs due to the inflammatory response triggered by the injury, while bruising results from blood vessel damage.

- Loss of range of motion is commonly reported by patients. This may be due to pain, swelling, and/or neuromuscular guarding of the injured ankle by the nervous system. Reduced range is usually seen after an injury has healed. Thus, it’s important to assess at follow-ups.

- Increased ankle laxity, instability or excessive joint mobility can be observed during physical examination. Patients may complain of recurrent episodes of their ankle giving way or feeling unstable, indicating ligamentous laxity.

Instability refers to a subjective feeling of the ankle being unreliable or giving way, which can significantly impact confidence and day to day life.

Time Frame of Healing

The duration of healing for ligament strains varies depending on the severity of the injury. However, as a general rule of thumb, the following timelines can be seen:

Grade 1 Strain: Typically, Grade 1 injury involves mild stretching or microscopic tears of the ligament fibres. In most cases, these strains heal within a relatively short period, ranging from 1 to 14 days. With appropriate management and rehabilitation, people can expect a quick recovery.

Grade 2 Strain: Grade 2 injury involves a moderate level of ligament fibre tearing. The healing process for these strains generally takes longer than Grade 1 strains. Patients can expect a healing timeframe of around 14 to 21 days.

Grade 3 rupture: Grade 3 strains are the most severe, they involve complete ligament tears or significant disruption. Healing for Grade 3 strains is a more prolonged process compared to lower-grade strains. Typically, patients should anticipate a healing period of approximately 6 to 12 weeks.

It is important to note that these timelines are general estimates and can vary among individuals depending on factors such as overall health, diet, adherence to rehabilitation protocols, and the demands placed on the injured ligament.

The Role of Imaging in Lateral Ankle Sprains

Imaging is a valuable tool in determining the extent and severity of ankle sprains, particularly in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain, or when there is suspicion of other structural damage such as bone breaks.

Whilst most ankle sprains can be diagnosed clinically based on physical and subjective assessments, imaging can provide additional information that helps guide treatment decisions.

Depending on the grade of the sprain a different treatment protocol will be followed, thus it’s beneficial to determine the severity to provide the best treatment plan.

Most ankle sprains will not need MRI, however, X-rays can be very useful.

X-ray:

They are typically performed first in ankle injuries to rule out fractures and assess the alignment of the bones. It can identify fractures or avulsion injuries, which will require different treatment than a simple sprain. X-rays are particularly important if there is significant pain, inability to bear weight, or if the mechanism of injury suggests the possibility of a fracture.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI is valuable for ankle sprains, especially when there is suspicion of associated soft tissue injuries, ligament tears, or if the clinical examination is inconclusive. MRI can provide detailed images of the ligaments, tendons, cartilage, and other soft tissues, helping to identify any tears, damage, or inflammation.

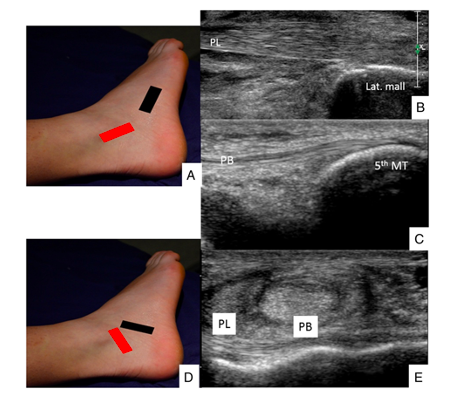

Ultrasound:

Ultrasound can be used to assess ligament integrity, identify fluid collections (such as hematomas), and evaluate tendon injury severity. It can provide real-time visualisation and can be used for guided injections or to assess healing progress during rehabilitation. Ultrasound is particularly useful in certain clinical scenarios, such as when assessing children or if MRI access is limited.

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan:

CT scans may be employed in cases where a fracture or bony injury is suspected but not adequately visualised on X-rays. CT scans provide detailed images of the bones and can assist in detecting subtle fractures, bone displacements, or other complex bony injuries.

Is Surgery Necessary?

Surgery for lateral ankle sprains is generally reserved for cases that have severe ligament damage or when conservative treatments fail to provide pain relief or stability. The decision to pursue surgery is typically based on several factors, including the extent of injury, functional impairment, instability, and the individual’s goals and lifestyle.

These are some things to consider:

When Surgery May Be Necessary:

- Complete Ligament Tear: If the lateral ankle ligaments (such as the ATFL and CFL) are completely torn or severely damaged, surgery is considered to repair or reconstruct the ligaments. This is more likely in cases where there is persistent instability, recurrent sprains, or significant functional limitations.

- Chronic Ankle Instability:If conservative treatments, such as physiotherapy and bracing have been unsuccessful in addressing ankle instability, surgery is considered. Chronic ankle instability refers to persistent feelings of giving way, recurrent sprains, or persistent pain and functional limitations.

- Athletes or Individuals with High Demands:Surgery may be recommended for people who participate in high-demand sports or activities that require a high level of ankle stability, such as professional athletes. Surgical intervention can help restore stability and reduce the risk of further injuries in these cases.

When Surgery May Not Be Necessary:

- Grade 1 and 2 Sprains:Most mild to moderate lateral ankle sprains can be effectively managed with conservative treatment, such as rest, compression and elevation, soft tissue work and rehabilitation.

- Adequate Healing and Stability:If Physiotherapy leads to symptom reduction and visible progression no matter how small, stability, and functional recovery, surgery is not necessary.

- Lack of Persistent Symptoms:If a person’s symptoms, such as pain, swelling, and instability, resolve with treatment and do not significantly impact their daily activities or quality of life, surgery is not considered.

It’s important to note that the decision to undergo surgery is individualised and should be made in consultation with an orthopaedic specialist or foot and ankle surgeon. They will assess the specific characteristics of the injury and the persons goals and expectations, and consider other relevant factors to determine the most appropriate course of treatment. Physiotherapists can make recommendations and refer people, if necessary, thus, knowing the signs is important.

Get the ACL assessment & rehab guide with over 50+ exercises to help you structure your rehab programme

I’ve spent over 1,000 hours studying sports medicine to give you the best tips and tools to succeed with your patients

Now, I’ve put everything I know about ACL’s into a simple guide… for free.

Risk Factors

Several factors contribute to the occurrence of lateral ankle sprains among patients & athletes, and understanding these factors can guide preventive strategies:

Previous Ankle Sprain History:

Patients with a history of previous ankle sprains are at a higher risk of re-injury. However, research has shown that people who wear ankle braces or use taping have a lower incidence compared to those who do not. These supports provide added stability and restrict excessive ankle movement, thereby reducing the risk of sprains (more on this later).

It’s also important to note that wearing bracing and/or tapping is an external crutch to the foot and thus will increase the ankles dependability on such support. It’s recommended to use bracing/tapping for full effort training sessions or competitive matches as these have the highest risks for sustaining ankles injury. Whilst warmups, rehab and light training session should be done without external support to enhance tissue adaptation and thus recovery from injury.

Shoe Selection:

Shoes with ankle support, such as high-top or lace-up designs, give additional stability and limit excessive ankle motion. By providing a more secure fit and restricting unwanted movements, these shoes can help prevent ankle sprains during sport.

Duration and Intensity of Physical Activity:

Prolonged and intense activity can lead to muscle and tendon fatigue, impairing their ability to support and protect the ankle joint effectively. As fatigue sets in, the muscles and tendons may become less capable to provide stability, increasing the risk of ankle sprains. Conditioning and monitoring fatigue levels can help mitigate this risk.

How To Assess An Ankle Sprain Objectively?

When examining ankle sprains, there’s a few things that need to be considered.

Swelling:

Evaluate the presence and the extent of swelling & bruising as it indicates the inflammatory response associated with the injury. Usually, the more severe the sprain is the more bruising and swelling you will see.

Ankle Joint Range of Motion:

Assess un-affected foot & ankle to determine the norm and move to the affected side. Look for any abnormalities or restrictions that may affect joint function. Usually, the range of motion will be affected by swelling, pain and muscle guarding in early phases.

Use a clinometer or the knee-to-wall test to understand the range in a more objective manner.

Gold standard:

- 39 degrees of dorsiflexion when using a clinometer

- 10cm from the wall when using the knee-to-wall test

Static Balance:

Evaluate the patient’s ability to maintain stability while standing still, which helps identify deficits in proprioception or postural control. Again, it’s important to determine normal level of balance. Test non-affected side first and time how long it takes until they either:

- Use opposite foot as support by anchoring to the planted foot

- Touch the floor with opposite foot

- Use hands for support on a wall

Gait Analysis:

Observe the patient’s walking pattern to detect deviations or compensatory movements (limping, hip hitching, knee hyperextension etc.).

Activity Level:

Take the person’s activity level into consideration to determine the appropriate treatment plan and timeline for return to sport. Some may be eager to return as soon as possible and are keen to follow the rehab plan. These people would benefit from a more challenging rehabilitation plan.

Whilst others may be fearful and avoidant or just may not have the time or motivation to participate in consistent rehab. This kind of patient would benefit from education and reassurance and a more progressive plan.

Special Tests For The Ankle

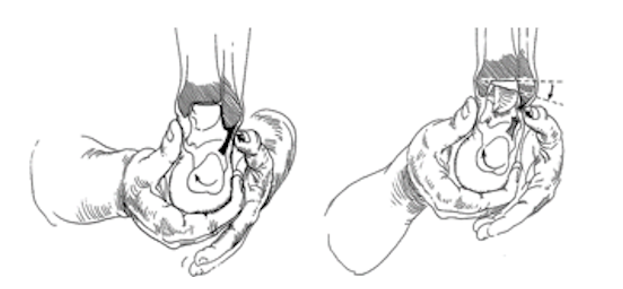

Anterior Drawer:

Helps to assess the integrity of the anterior talofibular ligament by evaluating forward displacement of the talus bone.

Talar Tilt Test:

Helps to understand the integrity of both the calcaneofibular ligament and anterior talofibular ligament by assessing the inversion and eversion movements of the ankle.

Squeeze Test:

Pressure around the lower leg helps to assess for potential syndesmotic irritation.

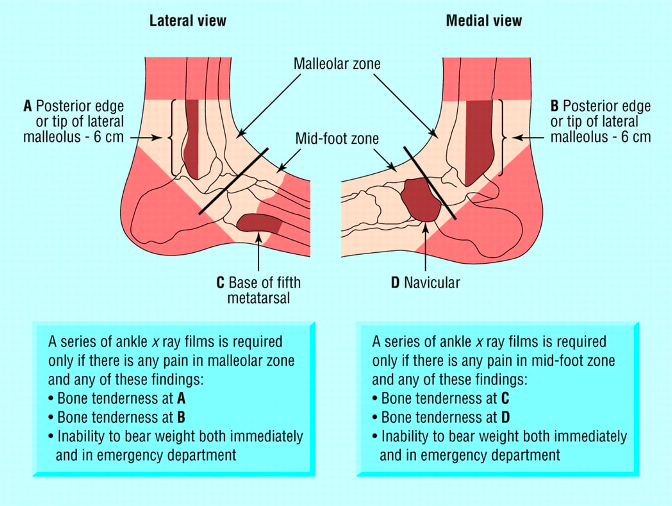

Ottawa Ankle Rules

The Ottawa ankle rules provide guidelines for determining the need for ankle and foot X-rays based on specific clinical criteria.

An Ankle X-ray is only required if:

There is any pain in the malleolar zone; and, Any one of the following:

- Bone tenderness along the distal 6 cm of the posterior edge of the tibia or tip of the medial malleolus

- OR Bone tenderness along the distal 6 cm of the posterior edge of the fibula or tip of the lateral malleolus

- OR An inability to bear weight both immediately and in the emergency department for four steps.

A foot X-ray series is indicated if:

There is any pain in the mid-foot zone; and, Any one of the following:

- Bone tenderness at the base of the fifth metatarsal (for foot injuries)

- OR Bone tenderness at the navicular bone (for foot injuries)

- OR An inability to bear weight both immediately and in the emergency department for four steps.

Early management for lateral ankle sprains (24-72 hours)

There are three primary goals to focus on when managing acute lateral ankle sprain in sport or clinic (grade 2 or 3):

- Pain management

- Inflammation control

- Joint protection

Functional rehabilitation has traditionally been emphasised, and should be followed for grade 1 sprains. However, there are important factors to consider when dealing with grade 2 & 3 due to the high recurrence rates of ankle sprains, the development of chronic ankle instability, and the potential development of ankle osteoarthritis in later years.

Ligament Healing and Stability:

Functional rehabilitation alone (exercises, weight bearing) may not allow enough time for the ankle ligaments to heal and restore stability. Research by Hubbard et al has shown that positive anterior drawer tests, indicative of ligament laxity, can persist in 3% to 31% of people six months after the injury. In addition, feelings of instability may also be present in 7% to 42% of patients up to one year after the injury.

Hence why we need to use interventions that prioritise ligament healing and address instability during rehabilitation.

Pain Management:

For managing lateral ankle sprains, rest and gentle range of motion exercises are often helpful in decreasing pain. For more severe cases, where pain is more intense, applying ice can be beneficial—though the role of cryotherapy remains a hot topic in sports medicine.

Some experts argue that avoiding ice during the first 48 hours may support the body’s natural healing processes, while others maintain that using ice doesn’t necessarily delay recovery or return to sport. With no definitive consensus in the research, using your clinical judgment to decide what’s best for each patient.

As for medication, anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen can curb inflammation, they may interfere with the early stages of healing. Simple analgesics like paracetamol can be a better choice, as they provide pain relief without dampening the inflammatory response that is important for healing.

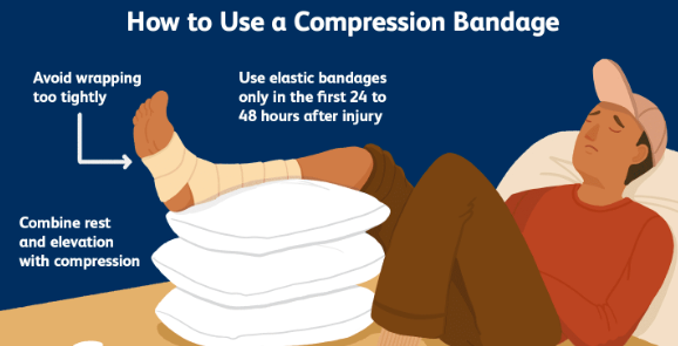

Inflammation Control:

As mentioned medicine that targets inflammatory process hinder healing, thus, using compression and elevation are ideal to help with waste removal

Joint Protection:

In the initial stages of a 2nd or 3rd grade ankle sprain allow the body to do its magic. Our systems are extremely good at dealing with initial injuries as long as they are not severe. Advising minimal weight bearing and strapping the ankle for the first 48-72 hours will protect the tissues from further damage.

Light ROM exercises such as ankle pumps and writing the alphabet with toes is okay and will promote healing via waste removal.

Exercise-Based Management

For effective ankle rehabilitation following an injury, it’s good practice to have a systematic approach that prioritises both ligament healing and the enhancement of stability.

First, promoting ligament healing is essential, and this can be achieved through progressive weight-bearing, proprioceptive training, and isolated strengthening exercises. These interventions should be introduced at the appropriate stages of the healing process to ensure the integrity of the ligaments is maintained.

Second, once the initial healing phase is underway, the focus should shift to stability. This involves exercises that improve proprioception and neuromuscular control, such as single leg balance, functional movements, and sport-specific drills tailored to the persons goals.

Phase 1: Acute Management

During the initial phase of an acute ankle sprain the following 4 strategies are recommended:

- Rest: Allow the injured ankle to rest for 48-72 hours to reduce stress on the affected ligaments and tissues.

- Compression: Compression to the ankle helps control swelling and provides support to the ankle joint.

- Elevation: To reduce swelling by encouraging fluid drainage

- Functional Rehabilitation: Early mobilisation (72 hours and beyond) with appropriate support

Phase 2: Early Rehabilitation (1-4 Weeks)

During this phase, the main focus is to progress to single leg static control. It has been observed that postural coordination is impaired for at least four weeks after the injury.

Additionally, both the involved and uninvolved limbs show impaired balance relative to an uninjured control group within six weeks of an ankle sprain.

Prescribe single leg balance exercises to enhance stability and proprioception as well as isolated joint movements (depended on sprain grade/pain can implement isometric ankle exercises)

This will be a general outline and treatment should be tailored to each individual person. Some exercises in phase 3 can be used in phase 2 and vice versa. The list of exercise is to provide some ideas, however, many more alternatives can be used to challenge the body.

Exercises:

- *Isometric inversion/eversion

- Single Leg Reach Outs: Extend the single leg outward in different directions to challenge balance and control.

- Single Leg Balance with Rotations: Perform rotations of the torso while maintaining balance on one leg.

- Single Leg Romanian Deadlifts (RDL’s): Improve strength and stability in the ankle and surrounding muscles.

- Tip Toe Walking and Tandem Walking: Gradually progress from walking on tiptoes to walking in tandem to challenge balance and coordination.

- Single Leg Swings: These exercises help improve dynamic stability and control of the ankle joint.

Phase 3: Long-Term Rehabilitation (Beyond 4 Weeks)

In the long-term rehabilitation phase, more complex exercises can be introduced to further strengthen the ankle joint and surrounding muscles. The focus shifts to enhancing functional movements and regaining full mobility.

Exercises

- Lateral Lunges: Incorporate lateral lunges to work on lateral stability and strengthening.

- Full Range Squats: Gradually progress to full squats to improve ankle strength and mobility in a weight-bearing position.

- Hopping: Controlled hopping exercises can help restore confidence and dynamic stability.

- Tibialis Anterior Curls: Target the tibialis anterior muscle for improved dorsiflexion control.

- Calf Raises: Calf muscles play a crucial role in ankle stability during walking and running.

- Lateral/Medial Ankle Movements with Resistance Band: Use resistance bands to challenge ankle stability in different directions.

- Side Walking with Band on Knees: A lateral resistance exercise that further enhances ankle control.

- Sprinting: Gradually reintroduce sprinting to simulate real-life dynamic movements.

Phase 3.1: Balance

Balance training is a critical component of ankle rehabilitation. It capitalises on the plasticity (ability to adapt) of the central nervous system, helping patients improve their response to both internal and external challenges.

Exercises

- Beam Walk: Walk along a narrow beam or raised surface to challenge balance and proprioception.

- Step Ups: Step onto an elevated platform, alternating legs to improve dynamic stability.

- Hopping in Different Directions: Practice hopping forward, backward, and side-to-side to enhance balance and coordination.

- Single Leg Exercises on Uneven Surfaces: Use foam pads or balance boards to challenge stability further.

- Hip Rotations: Incorporate hip rotations during single-leg exercises to improve multi-joint coordination.

Get the ACL assessment & rehab guide with over 50+ exercises to help you structure your rehab programme

I’ve spent over 1,000 hours studying sports medicine to give you the best tips and tools to succeed with your patients

Now, I’ve put everything I know about ACL’s into a simple guide… for free.

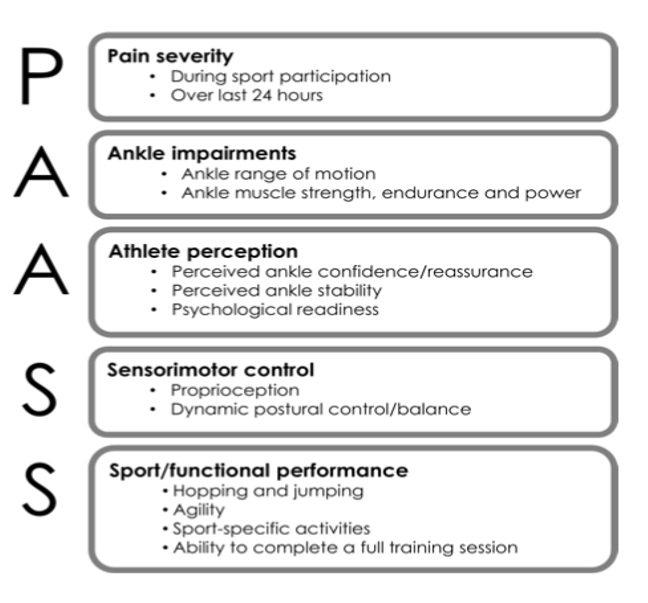

Returning To Sport After Latera Ankle Sprain

There are 4 important metrics to consider when doing a return to sport assessment.

- Confidence & Readiness

- Static control

- Dynamic control

- Gradual progression

Perception and Readiness

When determining an athlete’s or patient’s ability to return to their sport after an ankle sprain, consider their subjective feelings toward the injury. Start by having a conversation to assess three key aspects:

- Their perception of ankle stability

- Their confidence in returning to high-intensity training and games

- Their psychological readiness—such as any fear avoidance or catastrophising.

Understanding the person’s feelings about returning to play helps to guide the gradual introduction. Physical readiness is essential, but confidence and mindset can significantly influence their success in return to sport.

Static Postural Control and Balance Assessment

Assessing static postural control and balance is important, as it helps gauge the person’s functional stability. A straightforward test is a single-leg balance assessment, where the individual stands on one leg for 30+ seconds.

Adding elements such as closing their eyes, moving their head side-to-side, or standing on an uneven surface can further challenge stability and give information about the ankle’s initial control and resilience.

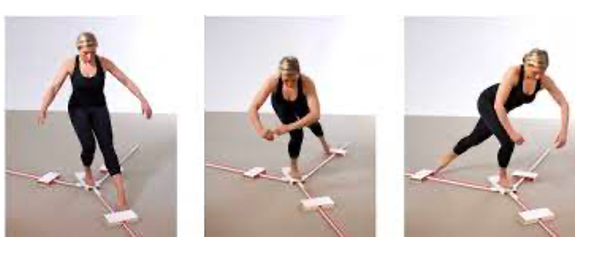

Dynamic Postural Control and Balance Assessment

Dynamic balance assessments, like the Y Balance Test, mimic the specific demands placed on the ankle during sports, revealing how well the athlete controls their body in motion.

Such tests challenge balance during dynamic movements, which is essential for sports readiness. Measure and compare reach distances on each side to identify any asymmetries.

Gradual Progression and Individualisation:

Every person recovers at their own pace, so it’s important to personalise the rehab program to fit their needs. Keep a close eye on their progress and adjust the plan as necessary. The key is to focus on gradual progression throughout the rehab process

Is Swelling Important?

While swelling often grabs our attention, it doesn’t always correlate directly with pain or functional limitations. It’s important to address it without letting it dictate the entire treatment approach.

Using manual therapy, such as light soft tissue work, can support fluid drainage if time permits, especially after a rehab session, allowing the body to recover and maintain comfort.

However, delaying a patient’s return to sport based on residual swelling alone isn’t justified if they’ve regained function and resolved other impairments. Instead, prioritise restoring ankle mobility, strength, and any remaining deficits that might impact performance. This approach ensures that the return to sport is based on true readiness rather than focusing solely on swelling.

Bracing & Taping The Ankle

Wearing ankle braces and/or tape during sports is effective at preventing recurrent lateral ankle sprains. These external supports provide added stability and reduce the risk of reinjury during unpredictable environments, such as games and full contact training.

Most ankle sprain occur in competition and more intense training sessions. It would be advisable to wear support for the first 6-12 months after injury in those scenarios to reduce risk of re-injury. However, bracing and support should be avoided during rehab session and light training to allow surrounding soft tissues to become stronger and more resilient.

Lace up braces for sport

Lace-up ankle braces are considered better than some other bracing options for ankle support. Here are some reasons why they might be preferred over other options:

- Adjustable fit: The lace-up design allows people to tighten or loosen the brace to their desired level of support and comfort.

- Enhanced stability: Lace-up braces offer more substantial lateral support.

- Lightweight and breathable: Many lace-up ankle braces are made from lightweight and breathable materials, making them more comfortable during prolonged use and reducing skin irritation.

- Improved proprioception: Lace-up braces allow for a close fit to the foot and ankle, which can help improve proprioception (awareness of the body’s position in space), enhancing overall ankle stability.

However, different people may have different preferences and needs when it comes to ankle support. Some might find other types of ankle braces, such as hinged braces or rigid stirrup braces, more suitable.

Air-Stirrup Brace with Elastic Wrap:

For grade I and grade II ankle sprains, using an Air-Stirrup brace combined with an elastic wrap in the first 1-3 weeks in moderate activities (longer walks, going to work etc.) has shown promising results in facilitating quicker return to pre-injury function compared to other immobilisers.

Below-Knee Cast for Severe Sprains:

In more severe ankle sprains, such as grade III, a below-knee cast may be the preferred choice. This level of immobilisation provides greater support and protection during the healing phase.

Elastic or Tubular Wraps Not Recommended:

Research suggests that elastic or tubular wraps do not offer sufficient protection to allow for the restoration of function. Therefore, they are not recommended as primary treatment options for early management of ankle sprains.

Joint Mobilisation

Joint mobilisation is thought to help manage lateral ankle sprains by reducing pain, improving function, and increasing range of motion. These benefits are theorised to occur through the restoration of arthrokinematics — the fundamental joint movements like rolling, gliding, and rotating.

For instance, high-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) thrusts applied over multiple sessions showed a lowering of self-reported pain levels. Additionally, using techniques like Maitland’s mobilisation and HVLA thrusts has been associated with improvements in both active and passive range of motion of the ankle.

However, It seem that a single treatment session, regardless of the technique, do not significantly impact the ankle’s range of motion, no matter if acute or chronic (those that happened more than six months ago) ankle sprain . So, for longer-term recovery, consistency and multiple sessions are key to seeing meaningful results

Balance Training

Stochastic Resonance:

Stochastic resonance involves introducing low levels of sub-sensory or mechanical noise into the nervous system during balance training. This technique enhances the sensorimotor system’s ability to detect afferent information from various sources, resulting in more efficient motor responses from the central nervous system, which is vital for maintaining balance.

Attentional Focus:

Incorporating attentional focus techniques into balance training can be a game-changer for improving motor skill learning and postural control. Attentional focus can be divided into two types:

- Internal attentional focus, where the person focuses on the body movement itself (like standing still)

- External attentional focus, which directs attention to the outcome of the movement (like reaching an object on the floor during single-leg RDLs).

Research consistently shows that external attentional focus leads to larger improvements in motor skill learning, as it enhances the acquisition, retention, and transfer of postural control skills. External cues also support more efficient movement patterns, allowing the sensorimotor system to self-organise and automate movements.

Other Conditions To Be Aware Of

| Condition | Characteristics & symptoms |

| Tendinopathy of tibialis posterior | Inflammation or irritation of a tendon or its covering (sheath) in the inner side of the ankle, resulting from repetitive small stresses that continuously strain the tendon. Common symptoms include swelling and activity-related pain |

| Bursitis | Refers to the inflammation of a bursa, a small sac filled with jelly-like fluid that acts as a cushion to reduce friction between bones and soft tissues. It occurs due to repetitive stresses and overuse, leading to swelling and redness at achilles insertion or lateral aspect of ankle. |

| Tendon full/ partial rupture | Tendon rupture or injury becomes evident when the affected muscle’s corresponding tendon fails to function, and a gap may be palpable in the tendon. This condition often results in the inability to move the ankle as well as presenting with notable swelling, feeling of snapping sensation during the incident and high level of pain/discomfort. |

| Achilles tendinopathy | degenerative condition affecting the Achilles tendon, resulting in pain, swelling, weakness, and stiffness in the area (link to prev article) |

| Stress fracture of tibia/tarsals | Stress fracture of tibia and the tarsal may present with pain at the shins or the ventral (top) aspect of foot with loading, this pain will progressively get worse as the activity continues. These fractures occur due to repetitive stress on the bone |

Sources

- Bridgman, S.A., Clement, D., Downing, A. et al. (2003) Population based epidemiology of ankle sprains attending accident and emergency units in the West Midlands of England, and a survey of UK practice for severe ankle sprains. Emergency Medicine Journal 20(6), 508-510.

- Cameron, K.L., Owens, B.D. and DeBerardino, T.M., 2010. Incidence of ankle sprains among active-duty members of the United States Armed Services from 1998 through 2006. Journal of athletic training, 45(1), pp.29-38.

- Hubbard, T.J. and Hicks-Little, C.A., 2008. Ankle ligament healing after an acute ankle sprain: an evidence-based approach. Journal of athletic training, 43(5), pp.523-529.

- Hubbard, T.J. and Wikstrom, E.A., 2010. Ankle sprain: pathophysiology, predisposing factors, and management strategies. Open access journal of sports medicine, 1, p.115.

- Hubbard, T.J. and Wikstrom, E.A., 2010. Ankle sprain: pathophysiology, predisposing factors, and management strategies. Open access journal of sports medicine, 1, p.115.

- Hubbard, T.J., S.L. Aronson, and C.R. Denegar, Does Cryotherapy Hasten Return to Participation? A Systematic Review.J Athl Train, 2004. 39(1): p. 88-94

- Smith, M.D., Vicenzino, B., Bahr, R., Bandholm, T., Cooke, R., Mendonça, L.D.M., Fourchet, F., Glasgow, P., Gribble, P.A., Herrington, L. and Hiller, C.E., 2021. Return to sport decisions after an acute lateral ankle sprain injury: introducing the PAASS framework—an international multidisciplinary consensus. British journal of sports medicine, 55(22), pp.1270-1276

- Tiemstra, J.D., 2012. Update on acute ankle sprains. American family physician, 85(12), pp.1170-1176.

Justas Muzikevicius

Justas is an experienced physiotherapist, author and founder of Sports MedU. From his experience as a professional athlete and now as a sports medicine expert he spends his time researching, writing and teaching clinicians how to put research into practice.

He enjoys basketball, reading and delicious food!

How Understanding The Calf Muscle Can Improve Sprint Performance

You May Also Like

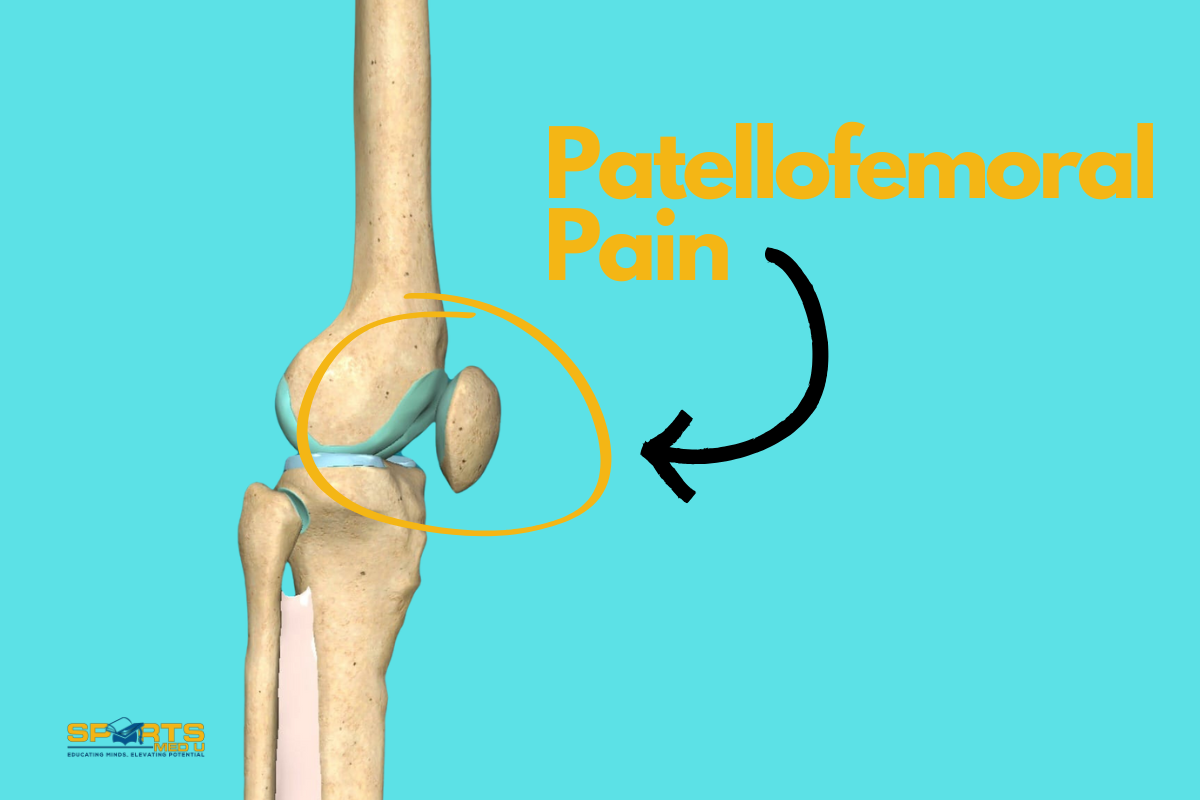

Patellofemoral Pain: Everything There Is To Know

Let’s dive into one of the most common (and tricky!) knee problems out there: Patellofemoral Pain

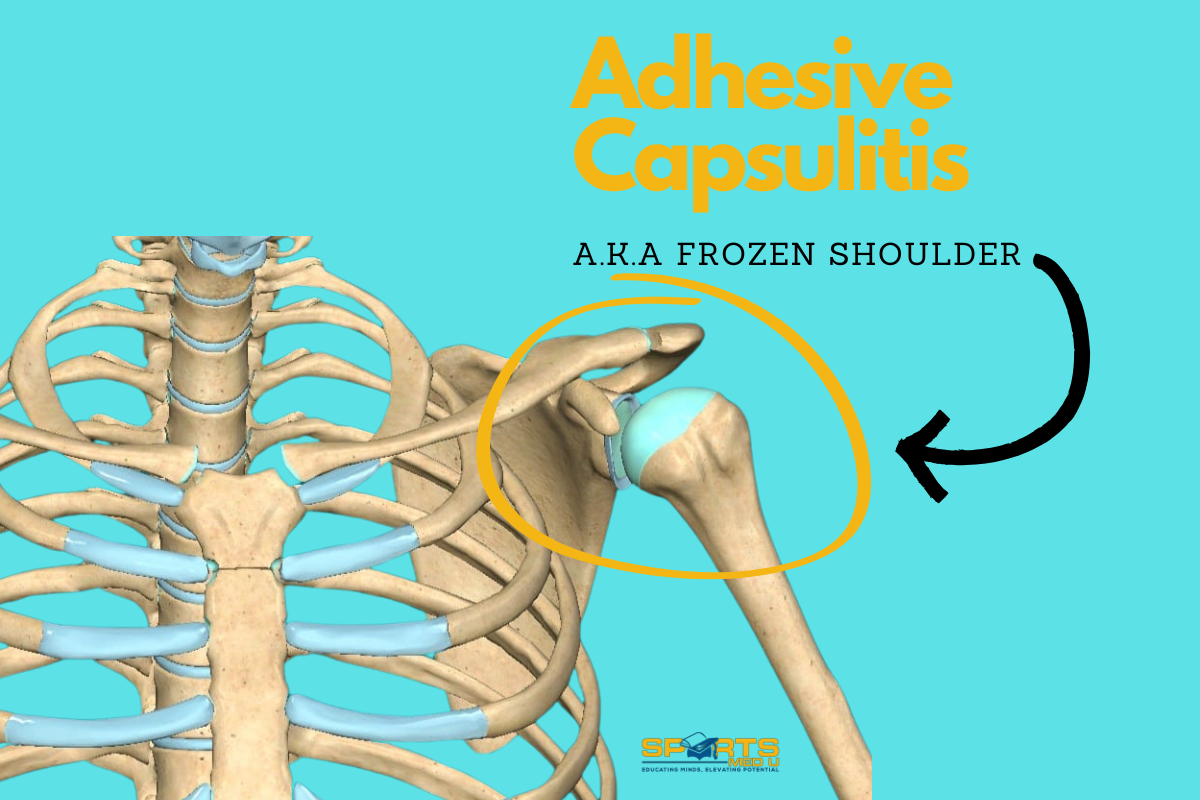

Cracking the Code of Frozen Shoulder: What You Need to Know

Imagine waking up one morning and realising you can no longer lift your arm without sharp pain or st

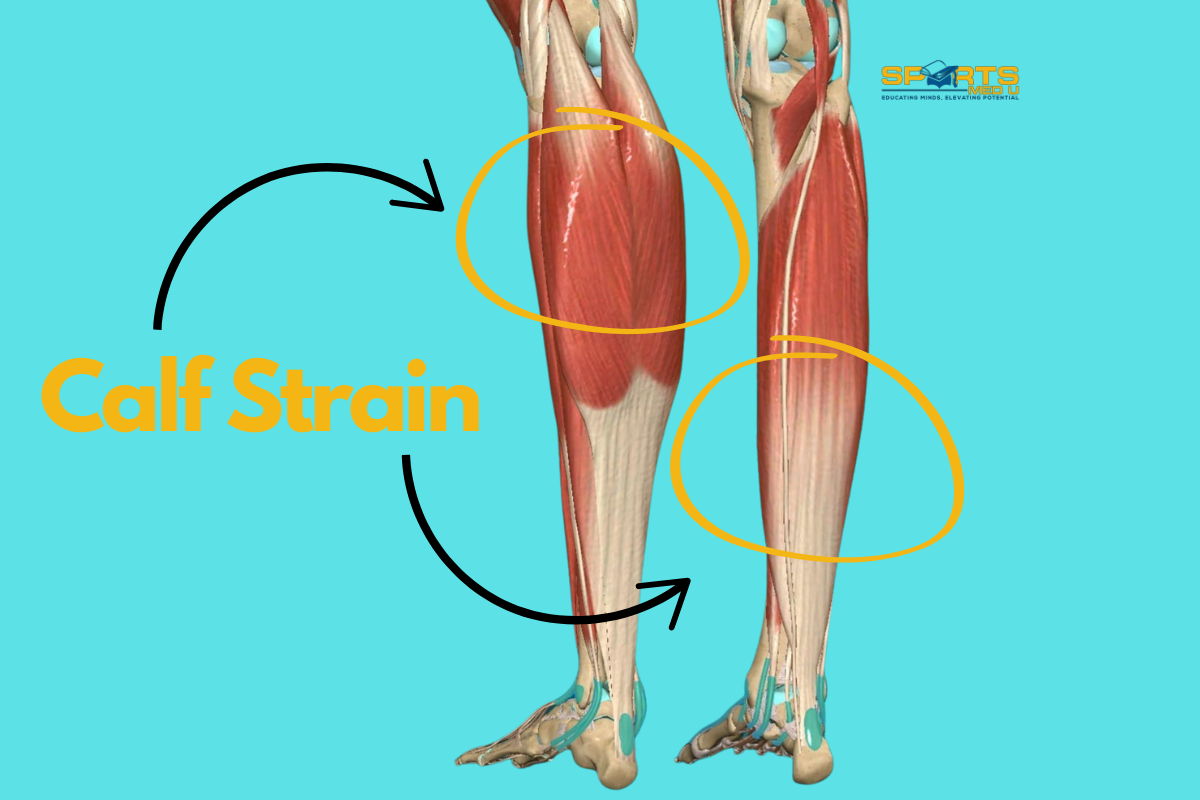

Calf Strains: Everything There Is To Know

Let’s talk about a common yet often underestimated injury: calf strain. Whether the person is an a