6 vital areas to focus on early after ACL surgery

ACL rehabilitation, while surgical intervention can restore knee stability, the post-operative journey is multi-factorial. Surprisingly, only 80% of recreational ACL reconstruction (ACLR) patients successfully return to some form of sports activity, and a mere 65% reach their pre-injury performance levels. A more alarming statistic emerges within the first two years post-return to sports, where one-third of young athletes face the risk of re-injuring their ACL. This underscores the importance of a comprehensive rehabilitation strategy.

Strikingly, after three years post-ACLR, only 65% of elite male footballers continue competing at their previous level, while 62% of female players abandon football due to knee injuries within two years. The potential onset of knee osteoarthritis symptoms is heightened by initiating sports activities at low functional levels early on. It becomes evident that the absence of high-quality early-stage and pre-operative rehabilitation contributes to significant functional limitations, hindering progress through mid- and later stages of rehabilitation.

In this articles we will discuss 6 key areas outlined by Buckthorpe & colleagues to focus on early after ACL reconstruction and the reasons why.

Let’s jump in

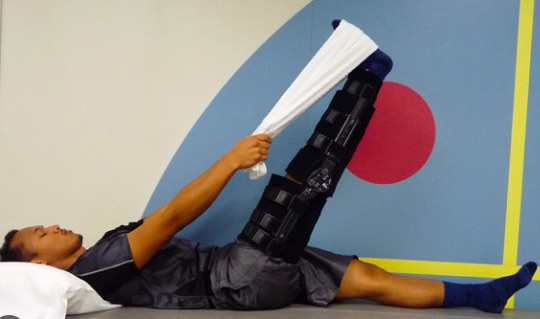

6 key principles to focus on include

- Pain/swelling

- Knee Range of motion

- Quad strength

- Movement quality

- Psychology

- Cardiovascular fitness

Sign up to our free breakdowns of research studies HERE

ACL Rehabilitation: Pre-Operative, Early, Mid, and Late Stages

The pre-operative phase emerges as a crucial determinant in ACLR outcomes, highlighting the significance of optimising knee function before surgery. Patients demonstrating full knee extension, minimal swelling, and no extension lag during preoperative assessments tend to fare better post-surgically, reducing the risk of complications such as arthrofibrosis.

The “early stage” immediately following ACL reconstruction takes center stage, addressing surgical and injury-related effects while laying the foundation for subsequent rehabilitation phases. Pre-operative rehabilitation programs, lasting 5-6 weeks and emphasising muscle strength restoration, quadriceps development, and hop performance, have shown promise in enhancing post-surgical knee function.

Moving into the “mid-stage” of rehabilitation, the focus shifts to three key objectives:

- Restoring muscle strength

- Improving movement quality

- Enhancing overall fitness.

These elements are pivotal in preparing individuals for the subsequent “late-stage” rehabilitation, where the emphasis lies on regaining fitness, optimising neuromuscular and movement performance, and engaging in comprehensive return-to-sport training. This final phase includes sport-specific on-field rehabilitation, return to training, competition, and ultimately reaching peak athletic performance. Navigating through these stages systematically is essential for a successful ACL recovery journey.

Pain and Swelling after ACL reconstruction: Strategies for Management and Monitoring

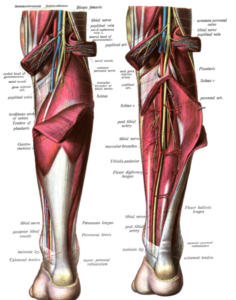

Following surgery, patients commonly encounter discomfort, swelling, and signs of inflammation, which can adversely impact joint proprioception and lead to muscle inhibition.

Standard practices in the early management of these symptoms involve cryotherapy (ice), compression, and elevation to mitigate joint inflammation and pain post-ACLR. Integrating active range of motion exercises, such as stationary cycling, aquatic tasks, and isotonic exercises, proves beneficial in promoting blood circulation, reducing swelling, and facilitating the restoration of knee range of motion.

Frequent medical consultations, typically every 10-15 days, are advisable to monitor progress and address potential complications. Monitoring pain, often assessed using a numeric rating scale, is crucial for tailoring rehabilitation efforts. To progress to higher-intensity rehabilitation stages, a knee-specific pain value of 0-2 is recommended.

Differentiating between tolerable scar tissue-related pain and pain at the harvest site is essential. Regular recording of swelling, using methods like the Stroke test and knee circumference measurements, aids in tracking progress. Clinically significant changes in knee circumference, considered greater than 1 cm increase can put extra load in the joint.

In case of increased swelling and soreness, program adjustments and patient education on load management become essential components of the rehabilitation journey.

Emphasising Knee Range of Motion in Early-Stage Recovery

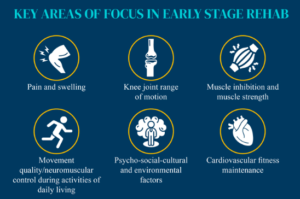

Early-stage rehabilitation should prioritise the restoration of knee joint extension and flexion to mitigate potential negative impacts on late-stage outcomes. Adequate joint ROM is not only essential for normal gait biomechanics but also critical in preventing complications such as abnormal joint movement, cartilage pressure, and quadriceps inhibition resulting from a loss of knee extension.

ACL reconstruction patients with extension deficits face a significantly higher risk of developing anterior knee pain, highlighting the importance of addressing these deficits early in the rehabilitation process. Educating patients on the non-harmful effects of passive extension stretching on the ACL graft is key to fostering compliance and progress.

Attaining a range of motion of 110–120° of knee flexion within 4–6 weeks is a pivotal milestone, enabling patients to engage in activities like stationary cycling and treadmill running. Gradual recovery of knee flexion ROM is especially crucial in cases involving associated surgical procedures, such as meniscal repair.

Early initiation of joint motion is instrumental in preventing capsular contractions, reducing swelling and pain, without adversely affecting joint laxity. Techniques such as active and passive ROM exercises, along with hydrotherapy, play a vital role in improving joint swelling and ROM during the early stages of ACL rehabilitation.

Muscle Activation and Strength in ACL Rehabilitation: Strategies for Early-Stage Success

Rebuilding knee extensor muscle strength stands as a primary goal, as deficits in size and strength can impede knee function and hinder overall progress. Weak knee extensors are associated with complications such as altered gait biomechanics, reduced dynamic stability, persistent knee pain, increased risk of knee osteoarthritis, and suboptimal return-to-sport outcomes.

Observing deficits of 40-60% in maximal voluntary force in the injured knee 4-6 weeks post-ACLR is common, emphasising the importance of early intervention. The strength of knee extensors at 6 weeks post-ACLR can predict hop and jump performance at the 6-month mark, influencing long-term outcomes.

Rehabilitation activities play a crucial role in early-stage outcomes by addressing issues like anterior muscle imbalances and quadriceps lag. The loss of mechanoreceptors from the ACL can impair the reflex between the ACL and quadriceps, hindering motor unit recruitment. Overly aggressive loading or high-force exercises in the early stage can jeopardise the integrity of the ACL graft/fixation sites and result in complications like patello-femoral pain syndrome.

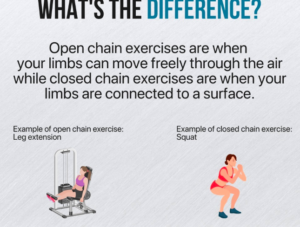

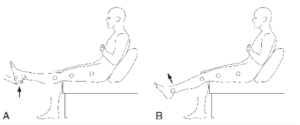

Selecting appropriate exercises during the early stage is challenging, necessitating a balance between quadriceps strengthening and avoiding deficits. Recommended early-stage exercises include isolated and non-weight-bearing tasks like leg presses or knee extensions, along with basic functional tasks such as bilateral squatting for movement restoration.

Incorporating both closed kinetic chain (CKC) and open kinetic chain (OKC) exercises is crucial, with OKC exercises proving effective for isolating muscles and promoting complete activation. Consideration of loading intensity is vital, with a focus on lower loads, high repetitions, and minimal recovery time between sets to target muscle endurance, work capacity, and hypertrophy.

ACL Rehabilitation and the Return to Sport Process

A successful return to sport involves not only addressing knee impairments but also reinstating neuromuscular function and preparing for sports-specific readiness, encompassing fitness, technical training, load readiness, and psychological preparedness.

The rehabilitation and return-to-sport process present an opportunity to elevate an athlete’s physical fitness beyond their pre-injury state, provided appropriate planning is in place. Notably, some patients, including professional football players, experience decreased cardiovascular fitness six months post-ACLR, highlighting the need for early introduction of cardiovascular fitness training.

While early-stage fitness preservation and reconditioning are crucial, they should not overshadow the primary focus on joint and functional recovery. Early-stage reconditioning components include addressing cardiovascular fitness deficits, preventing muscle mass/strength loss in adjacent joints and the contralateral limb through contralateral strength training, and averting increases in body fat. A comprehensive and balanced approach to physical fitness preservation ensures a robust foundation for athletes to reclaim peak performance levels post-ACLR.

Guidance for Early Rehab after ACLR

Quadriceps Strengthening in ACL Rehabilitation

Quadriceps strengthening should be emphasised when patients experience minimal pain (0–2) and swelling, coupled with sufficient quadriceps activation, evidenced by no lag on a straight leg raise.

Incorporating neuromuscular electrical stimulation and/or passive blood flow restriction during the initial weeks can enhance outcomes, complementing early isometric exercises. Isometrics performed at a restricted range of motion (e.g., 60° and/or between 90° knee flexion) with repetitive sustained holds (e.g., 5 sets of 45 seconds with 2 minutes of rest between each repetition) prove beneficial.

During the transition to mid-stage rehabilitation, assessing knee extensor muscle strength, including both morphological and neural aspects of neuromuscular function, becomes crucial. Utilising a portable dynamometer, ideally an isokinetic or isometric build dynamometer, for isometric knee extensor strength assessment at/or between 60–90° knee flexion is recommended.

Continuous monitoring of knee extensor workloads and the knee’s response to loading, such as pain, swelling, and knee circumference, throughout this stage and subsequent phases, aids in tailoring rehabilitation strategies for optimal outcomes. This clinical guidance serves as a roadmap for clinicians aiming to navigate the intricacies of quadriceps strengthening in ACL rehabilitation.

Integrating Land and Water-Based Re-training in Early ACL Rehabilitation

In the ever changing landscape of ACL rehabilitation harnessing neuroplasticity is key. A comprehensive approach involves incorporating both land- and water-based gait, balance, and foundation movement re-training during the early stage. Exercises like bilateral squats and step-ups in the pool serve as effective modalities for promoting neuroplastic changes.

Implementing a walking gait re-education program becomes essential, covering aspects such as crutch use, control during knee extension–flexion range of motion, hip adduction during the stance phase, dynamic stability, and selective movement retraining exercises. This holistic program contributes to neuroplastic adaptation, optimising gait patterns, and improving overall movement quality.

Additionally, assessing the bilateral squat technique and limb loading as part of early-stage criterion-based rehabilitation ensures a focus on good technique and limb loading, with the goal of achieving a deficit of less than 20%.

Source:

- Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, et al. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1543

- Buckthorpe, M., Gokeler, A., Herrington, L., Hughes, M., Grassi, A., Wadey, R., Patterson, S., Compagnin, A., La Rosa, G. and Della Villa, F., 2023. Optimising the early-stage rehabilitation process post-ACL reconstruction. Sports Medicine, pp.1-24.

- Waldén M, Hägglund M, Magnusson H, Ekstrand J. ACL injuries in men’s professional football: a 15-year prospective study on time trends and return-to-play rates reveals only 65% of players still play at the top level 3 years after ACL rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(12):744–50

Leave a Reply