Jumpers knee – Symptoms, risk factors & healing timeframe

Patellar tedninopathy, aka jumpers knee is a common and a pretty simple condition to diagnose if you know the key facts. It affects mainly jumping and explosive athletes, but can appear in people that exercise as a hobby and/or for health.

Have you ever pondered the inner workings of your knees as they effortlessly facilitate your movements, such as walking, running, and leaping? The key lies within the remarkable domain of the patellar tendon – a modest yet robust component within your knee joint.

In this informative article, we will explore patellar tendinopathy and its risk factors, mechanism of injury, imaging and much more.

Let’s explore the simple, yet complex pathology of patellar tendinopathy.

5 Key takeaways of the article

- The patellar tendon, which links the kneecap to the shinbone, plays a vital role in knee biomechanics by facilitating leg extension and transferring force between the quadriceps and shinbone.

- Patellar tendinopathy, often referred to as “jumper’s knee,” results in localized discomfort near the tendon and frequently impacts athletes due to repetitive, high-impact activities.

- Common symptoms encompass pain experienced during actions such as squatting, jumping, and prolonged sitting, often accompanied by crepitus sensations, particularly noted in females.

- Excessive strain due to sudden increases in physical activity serves as a primary contributor, leading to discomfort and pain within the patellar tendon.

- Risk factors associated with patellar tendinopathy encompass training aspects (intensity and frequency), physical attributes (height, weight, flexibility), muscle characteristics (length and strength), forces acting on the patellar tendon, anatomical considerations (foot arch, ankle flexibility, leg length disparities), and a higher incidence among males compared to females.

What is the patellar tendon and its role?

The patellar tendon, also referred to as the patellar ligament, is a crucial structure in the knee joint responsible for connecting the kneecap (patella) to the shinbone (tibia). It plays a pivotal role in the knee’s biomechanics, facilitating the straightening or extension of the leg and enabling the transfer of forces between the thigh muscles (quadriceps) and the shinbone.

Let’s delve further into the significance, origin, and insertion of the patellar tendon:

Role:

The principal function of the patellar tendon is to convey the force produced by the quadriceps muscles to the tibia, which results in the extension of the knee joint. It also serves to stabilise the position of the patella and maintain its proper alignment within the groove of the femur during various leg movements.

Origin:

The patellar tendon originates from the lower part, or the inferior pole, of the patella. This is where the tendon originates and attaches itself to the kneecap.

Insertion:

The insertion point of the patellar tendon is the tibial tuberosity, a prominent bony structure located on the front side of the tibia, just below the knee joint. This is where it firmly attaches and secures itself, allowing for the efficient transmission of the muscular force generated by the quadriceps to the shinbone.

When the quadriceps contract, the patellar tendon exerts a pull on the patella, which, in turn, applies force to the tibia. This action leads to the straightening or extension of the knee joint, which is essential for various activities such as walking, running, jumping, and other lower limb movements.

What is patellar tendinopathy?

Patellar tendinopathy, known as “jumper’s knee,” causes localised pain around the patellar tendon. Pain occurs either close to the kneecap (proximal) or near the shinbone (distal). Middle tendon pain is rare, typically resulting from direct injury.

It’s common in athletes due to repetitive knee stress

Did you know

- Pain and dysfunction in the patellar tendon. It most commonly affects jumping athletes from adolescence through to the fourth decade of lie..

- Once symptoms are aggravated, activities of daily living are affected, including stairs, squats, stand to sit, and prolonged sitting.

- Patellar tendinopathy clinically presents as localised pain at the proximal tendon attachment to bone with high-level tendon loading, such as jumping and changing direction. tendon-loading task (such as jumping and changing direction)

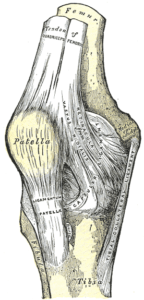

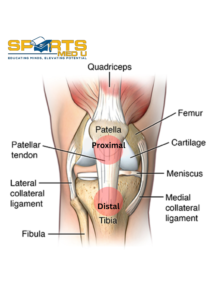

Anatomy of the knee

To fully understand patellar tendinopathy its important to know the anatomy of the knee.

Let’s have a quick look

Bones:

The knee joint is primarily formed by three bones:

- Femur: The upper thigh bone.

- Tibia: The larger of the two lower leg bones and the main weight-bearing bone.

- Patella: The kneecap, a small, flat bone that sits in front of the knee joint and protects it.

Ligaments:

Ligaments are tough, fibrous tissues that connect bone to bone and provide stability to the joint. In the knee, there are four main ligaments:

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL): Prevents the tibia from moving too far forward in relation to the femur.

- Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL): Prevents the tibia from moving too far backward in relation to the femur.

- Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL): Provides stability to the inner part of the knee.

- Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL): Provides stability to the outer part of the knee.

Meniscus:

The menisci are two wedge-shaped pieces of cartilage (fibrocartilage) that act as shock absorbers and provide cushioning between the femur and tibia. They also help distribute the load evenly across the joint.

Muscles:

Several muscles surround and support the knee joint, including the quadriceps (front thigh muscles) and the hamstrings (back thigh muscles). These muscles play a vital role in movement and stability.

The epidemiology of patellar tendinopathy

Patellar tendinopathy is a condition resulting from excessive use, and it often develops gradually over time. Research indicates that the prevalence of this condition is notably higher in male athletes compared to female athletes.

Among the sports studied, basketball players had the highest incidence of patellar tendinopathy, with 36% of athletes in this sport experiencing this condition. The study examined various sports, including basketball, netball, cricket, and Australian football, to assess the prevalence of patellar tendinopathy among athletes.

Symptoms of patellar tendinopathy

People with patellar tendinopathy often present with 2 clear signs.

1. Pain During Activities:

When we talk about patellar tendinopathy, we’re referring to the discomfort that people often feel during certain activities. Think of actions like squatting, jumping, climbing stairs, or kneeling.

Typically, during longer activities the pain lingers at the start and slowly fades away as more time passes. Only to resurface again after coming home and/or the next day as a flare up.

Patellar tendinopathy often exhibits characteristic pain behaviour. Symptoms may include initial soreness at the start of physical activity, variable responses to warm-up (ranging from complete relief to no relief), and exacerbation of pain on the following day, which can persist for several days.

The big IF’s:

- If the patients muscles are not strong enough

- If The patient overloads the tissues and does not give enough time to recover

- If there’s imbalances in muscle strength/weight distribution/ hip & ankle range of motion

Then these activities place a large amount of load on the tendon. And when those structures are stressed, it can lead to pain/discomfort.

2. Prolonged Sitting:

Here’s another interesting aspect. If you have patellar tendinopathy, sitting for a long time can make your symptoms worse.

Why?

This creates tension in the collagen fibres which stimulates the nociceptors, leading to that tell tale sign of discomfort.

Enjoying the article? Have a look at our analysed studies – HERE

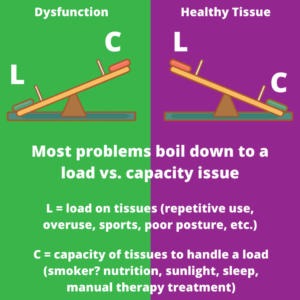

Mechanism of injury

As with most tendinopathies the primary cause is overload. Overload in the context of patellar tendinopathy happens when there’s more physical activity than the tendon has become accustomed to handling at a given time. This overload can occur when there’s a sudden and significant increase in activities like jumping or when someone resumes their regular routine after an injury or a break without gradually easing back into it.

Now, let’s unpack this for you. Imagine you’re an athlete, and you’ve been training regularly, but then you had to take a break due to an injury or maybe a vacation. When you return the tissues capacity to take load has decreased and thus when training routine starts abruptly, without giving your body time to adapt slowly, it gives your tendons more stress that they can handle.

How long will it take for patellar tendinopathy to heal?

Patellar tendinopathy treatment typically resolves initial injury symptoms in around six weeks.

However, achieving full recovery can extend from weeks to months, especially when physical therapy is involved. In some cases, complete rehabilitation may even take years, particularly for chronic or severe conditions

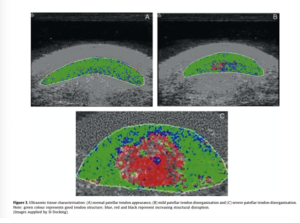

Imaging

Utilising conventional ultrasound and MRI techniques can help effectively detect abnormalities within the patellar tendon.

However, in most cases, when using imaging, it will reveal some form of tendon abnormality. it’s crucial to note that just because an imaging study shows these abnormalities, it doesn’t necessarily imply that the identified pathology is the primary cause of pain.

Patellar tendinopathy can be easily diagnosed with subjective (location & symptom behaviours) and objective assessments. Most importantly we treat the cause of symptoms and the present discomfort, rather than the imaging findings.

Is surgery common for patellar tendinopthy?

When it comes to dealing with jumper’s knee, surgery is typically reserved as a last-resort option. Most instances of patellar tendinopathy can be effectively addressed using non-surgical methods. Bahr and colleagues found no difference between eccentric training and surgery people with sever patellar tendinopathy in respect to functional ability and VISA-P score after 3,6 & 12 months.

However, if non-surgical approaches have been exhausted and the condition remains severe or unresponsive to other treatments, surgery may become a consideration.

Below, are various surgical alternatives for patellar tendinopathy:

Debridement:

This surgical procedure involves the removal of damaged or deteriorated tissue from the patellar tendon. Debridement can be done in a minimally invasive manner using arthroscopy, where small incisions and a camera guide the surgeon.

Tendon Repair:

When there’s a partial tear or significant damage to the patellar tendon, surgical repair might be necessary. During this operation, the surgeon sutures or reconnects the torn sections of the tendon.

Tendon Transfer:

In rare cases where the patellar tendon is severely compromised and cannot be repaired, a tendon transfer will be on the table. This procedure entails using another tendon, like the hamstring, to replace the damaged patellar tendon.

Tenotomy:

Sometimes, when other surgical options are unsuitable, a surgeon may opt for a tenotomy. This involves cutting a portion of the patellar tendon to alleviate tension and reduce pain.

Risk Factors associated with patellar tendinopathy

Training Factors:

Several studies have linked an increase in training intensity and frequency to the development of patellar tendinopathy. Changes in training conditions, like harder surfaces with less shock absorption, can also play a role in worsening symptoms of patellar tendinopathy.

Physical Factors:

Certain physical characteristics can influence the risk of patellar tendinopathy. These include factors like height, weight, flexibility of lower limb joints, leg length, body composition, alignment of lower limbs, and the length and strength of thigh muscles like the quadriceps and hamstrings.

Muscle Length and Strength:

Shorter or less flexible quadriceps and hamstrings have been associated with an increased risk of patellar tendinopathy. On the other hand, greater strength in these muscles has been linked to reduced pain and improved function. Athletes with patellar tendinopathy, especially those involved in activities requiring energy storage for jumps, tend to have better knee extensor strength and jumping ability. This highlights the importance of context and individual based approach.

Force on the Patellar Tendon:

Research by Edwards and colleugues has shown that horizontal braking forces place the highest stress on the patellar tendon. They suggested that this stress, along with compression in the patellofemoral joint and tensile loading when the knee is bent, can contribute to the development of patellar tendinopathy, even in individuals without symptoms.

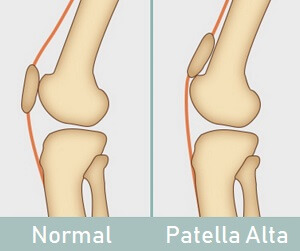

Anatomical Factors:

Some anatomical factors also influence the likelihood of developing patellar tendinopathy. These include having a lower arch height in the foot, reduced flexibility in ankle dorsiflexion, a greater difference in leg lengths, and a condition called “patella alta” in males.

Gender Differences: Boys and men are more prone to developing patellar tendinopathy, with a risk that is two to four times higher than that in women

Summary of article

- The patellar tendon, also known as the patellar ligament, connects the kneecap (patella) to the shinbone (tibia) and plays a crucial role in knee biomechanics, allowing leg extension and transferring forces between the quadriceps muscles and the shinbone.

- The patellar tendon originates from the lower part of the patella and inserts at the tibial tuberosity, facilitating knee extension and stabilizing the patella’s position within the femoral groove.

- Patellar tendinopathy, often called “jumper’s knee,” is characterized by localized pain near the distal attachment or in the middle, commonly affecting athletes due to repetitive high impact loading.

- Symptoms include pain during activities like squatting, jumping, climbing stairs, or kneeling, exacerbated by factors like weak muscles, overloading, and imbalances.

- Prolonged sitting can worsen patellar tendinopathy symptoms due to increased pressure on the kneecap and surrounding tissues.

- Crepitus, sensations of cracking, grinding, or popping, is reported, particularly by women, but it doesn’t necessarily correlate with function or pain severity.

- Overload, often resulting from abrupt increases in physical activity, is a primary cause of patellar tendinopathy, leading to pain and discomfort in the patellar tendon.

- Treatment typically takes around six weeks to alleviate initial symptoms, but full recovery may extend to months or even years, especially for chronic cases.

- Imaging can detect tendon abnormalities, but the presence of abnormalities doesn’t always indicate the primary cause of pain.

- Surgery is usually considered a last resort for severe or unresponsive cases of patellar tendinopathy, with non-surgical methods being the primary approach.

- Risk factors for patellar tendinopathy include training factors (intensity and frequency), physical characteristics (height, weight, flexibility), muscle length and strength, force on the patellar tendon, anatomical factors (foot arch, ankle flexibility, leg length differences), and a higher prevalence in males compared to females

Sources

- Bahr, R., Fossan, B., Løken, S. and Engebretsen, L., 2006. Surgical treatment compared with eccentric training for patellar tendinopathy (jumper’s knee): a randomized, controlled trial. JBJS, 88(8), pp.1689-1698.

- Edwards, S., Steele, J.R., McGhee, D.E., Purdam, C.R. and Cook, J.L., 2017. Asymptomatic players with a patellar tendon abnormality do not adapt their landing mechanics when fatigued. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(8), pp.769-776..

- Schwartz, A., Watson, J.N. and Hutchinson, M.R., 2015. Patellar tendinopathy. Sports health, 7(5), pp.415-420.

Leave a Reply