Rotator cuff related shoulder pain

Physiotherapists, brace yourselves for the exploration into the realm of rotator cuff-related shoulder pain. This article delves into injury mechanisms, clinical progression, and risk factors, equipping you with essential insights for effective care.

By understanding the intricacies of this condition, you’ll be primed to create impactful treatment strategies, transforming your patients’ shoulder health and overall well-being. Join us in deciphering the complexities of rotator cuff-related shoulder pain, enhancing your expertise and patient outcomes.

Let’s embark on this educational journey together.

5 key takeaways

- The rotator cuff muscles, including the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, work in a coordinated manner to stabilize the shoulder during different movements, and understanding their specialised recruitment patterns is crucial for preventing excessive joint movement.

- More than three million individuals annually seek medical attention for shoulder discomfort, with rotator cuff issues identified in 20.7% of cases, emphasizing the prevalence and significance of this condition.

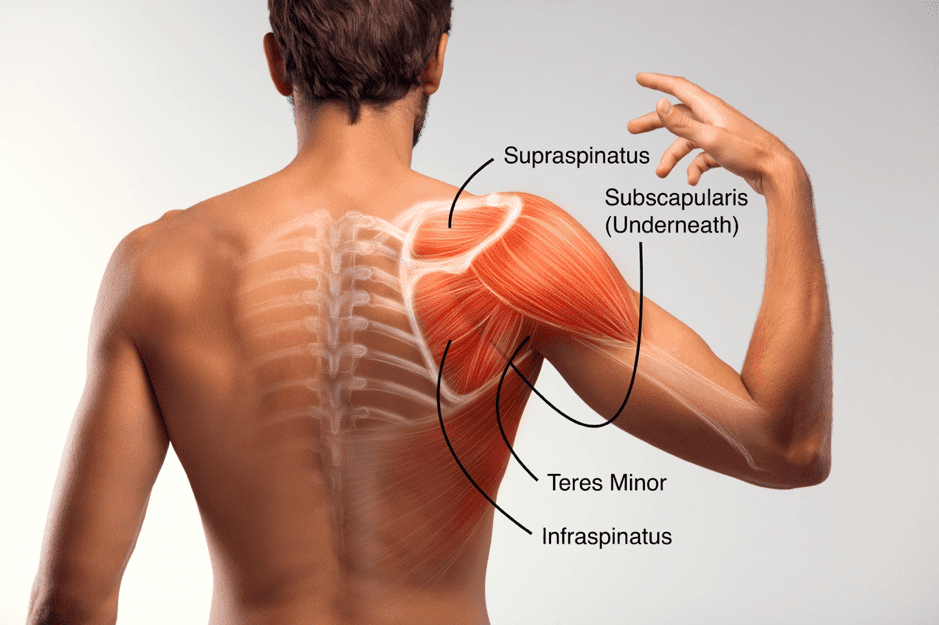

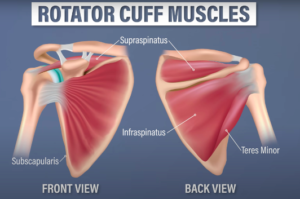

- Comprising of four muscles – supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis – the rotator cuff plays a vital role in providing stability & control with movement

- The unified structure of the rotator cuff tendons poses challenges in isolating specific muscle-tendon units for evaluation, making specialised tests focusing on individual muscles less useful in assessing this complex structure.

- Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain is thought to result from a combination of factors such as degeneration, overuse, and structural changes within the tendons, and while symptoms are often attributed to tendons, it’s crucial to acknowledge potential contributions from surrounding tissues.

Function of the rotator cuff

The muscles and tendons of the rotator cuff are commonly believed to work together in a coordinated manner to provide dynamic stability for the head of the upper arm bone (humerus) within the socket (glenoid fossa) during shoulder movement.

Research conducted in controlled environments indicates that the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles tend to be selectively engaged more during the act of raising the arm forward (shoulder flexion).

On the other hand, the subscapularis muscle shows increased activity levels when the arm is extended backward. This specialized recruitment pattern of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles during shoulder flexion might play a role in preventing excessive forward movement (anterior glide) of the humeral head when you’re performing actions that involve raising your arm.

Similarly, the heightened engagement of the subscapularis muscle during extension may contribute to limiting excessive backward movement (posterior glide) of the humeral head during activities that entail extending the arm.

In situations where the shoulder is raised to higher angles, like unsupported arm abduction, the stabilising function of the rotator cuff could potentially be taken over by the deltoid muscle. This could be due to the deltoid’s more favourable alignment for stabilising the humeral head within the glenoid fossa while allowing the rotator cuff muscles to focus on the external and internal rotation of the shoulder joint.

RCRSP stands for Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain. It refers to the typical symptoms of discomfort and limitations in shoulder mobility and function that often occur when raising the arm and rotating it outward. This condition is commonly seen in clinical practice and involves issues related to the rotator cuff muscles and tendon

Fun Facts

- More than three million individuals seek medical attention annually due to shoulder discomfort.

- Among these cases, the primary culprit is rotator cuff disease according to Yamamoto et al, their study of 1366 shoulders in the general population revealed that 20.7% had complete-thickness rotator cuff tears, with significant risk factors including age, dominant arm usage, and previous instances of trauma.

Anatomy of the shoulder

The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles and their tendons that surround the shoulder joint. As mentioned previously, these muscles play a crucial role in stabilising the shoulder and facilitating its movement.

Here’s an overview of each muscle’s origin, insertion, and function:

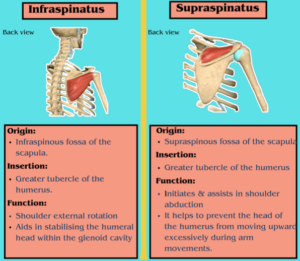

Supraspinatus Muscle:

Origin:

Supraspinous fossa of the scapula (shoulder blade).

Insertion:

Greater tubercle of the humerus (upper arm bone).

Function:

Initiates and assists in the abduction (raising) of the arm, especially in the first 15 degrees. It helps prevent the head of the humerus from moving upward excessively during arm movements.

Infraspinatus Muscle:

Origin:

Infraspinous fossa of the scapula.

Insertion:

Greater tubercle of the humerus.

Function:

Primarily responsible for external rotation of the arm, which involves turning the arm outward. It also helps stabilize the humeral head within the glenoid cavity during arm movements.

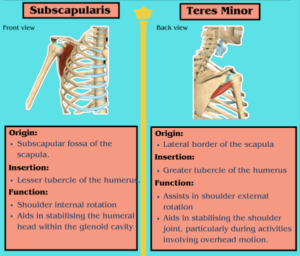

Teres Minor Muscle:

Origin:

Lateral border of the scapula.

Insertion:

Greater tubercle of the humerus.

Function:

Assists in external rotation of the arm and contributes to the stabilization of the shoulder joint, particularly during activities involving overhead motion.

Subscapularis Muscle:

Origin:

Subscapular fossa of the scapula.

Insertion:

Lesser tubercle of the humerus.

Function:

Primarily responsible for internal rotation of the arm. It also aids in stabilizing the humeral head within the glenoid cavity during arm movements.

Collectively, the rotator cuff muscles work in harmony to provide stability to the shoulder joint, control its movement, and allow for various arm motions. They also play a vital role in maintaining the proper alignment of the humeral head within the glenoid socket, which is crucial for optimal shoulder function and preventing injuries

Word of caution

The structure of the rotator cuff presents a challenge when trying to evaluate each individual muscle-tendon unit. The tendons that make up the rotator cuff join together to form a single unified structure.

Specifically, the tendons of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles become inseparably combined as they near their attachment points. Additionally, the muscular part of the teres minor and infraspinatus muscles also merge together just before reaching the point where muscle and tendon meet

Thus, specials tests looking at each specific muscle are not considered useful as the tests usually involves more than one muscle.

Learn how to test for RCRSP in our assessment & treatment article

Aetiology – The origin of RCRSP

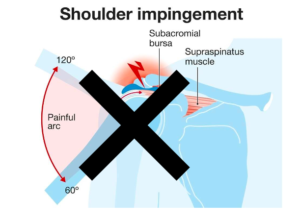

Acromion impingement?

The notion that irritation of the acromion contributes to problems with the rotator cuff lacks substantial support from observational studies. Payne et al found that out of 43 rotator cuff tears, 91% occurred on the inner side of the tendon near the joint, while only 9% were on the side under the acromion (known as the bursal side).

The consistent discovery that most tears happen within the tendon or on the joint side contradicts the theory of acromial impingement. Increased degeneration and misalignment were observed in the middle and deeper fibres of the RC, suggesting that degeneration is the primary trigger for rotator cuff tears.

The deeper fibres of the RC had a smaller cross-sectional area compared to the joint side fibres, and the lower fibres failed at about half the force of the upper fibres. Because the lower fibres are relatively weaker, it’s suggested that the joint-side fibres are more prone to strain compared to the bursal-side fibres

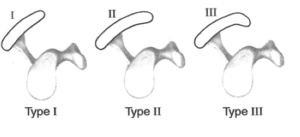

Shapes of the acromion

There are three distinct shapes of the acromion (flat, curved, and hooked), with variations attributed to morphology. It’s argued that those with a Type III or hooked acromion might be more prone to subacromial pain and rotator cuff tears.

However, a clear cause-and-effect relationship hasn’t been established, and the connection between acromial shape and symptoms appears weak.

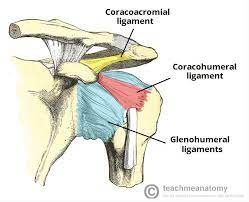

The coracoacromial ligament

The coracoacromial ligament could be a source of symptoms in individuals diagnosed with RCRSP. This group of patients showed significant increases in pain-related nerve fibres within this ligament. During discussions with patients, clinicians should avoid attributing rotator cuff tears or symptoms to the acromion. The term ‘impingement’ might wrongly suggest a certain cause of the problem.

Ongoing discussions continue within the field regarding several key aspects:

- The underlying causes of Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain

- The specific mechanisms responsible for generating the sensation of pain

- The interplay between the symptoms experienced and the observed structural deterioration occurring within the tendons of the Rotator Cuff

- The precise role and extent of inflammation in this context.

But it’s thought to involve a combination of factors such as degeneration, overuse, and structural changes within the tendons. Microscopic ‘tears’, repetitive stress, and age-related changes are believed to contribute to the development of RCRSP.

Commonly, the symptoms are collectively labelled as “rotator cuff tendinopathy,” implying that the tendons themselves are the source of the discomfort.

While this could indeed be accurate, it’s important to note that there isn’t a definitive method to conclusively attribute the painful sensations solely to the tendons. It’s plausible that the symptoms may stem from both the tendons and the surrounding tissues that are closely related to them.

Symptoms of RCRSP

Patients frequently describe experiencing shoulder discomfort while at:

- Rest

- During night-time

- When engaging in various overhead activities.

They commonly report pain when:

- Raising the arm above shoulder level

- Reaching behind the head

- Reaching behind the back

There are 3 types of RCRSP:

Irritable Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain :

This type of RCRSP can manifest in both sudden (acute) and prolonged (chronic) forms, often showcasing easily provoked and lingering shoulder pain. Additionally, it tends to be accompanied by night-time discomfort.

Non-Irritable Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain:

Non-irritable RCRSP is marked by varying degrees of pain, which intensifies with movement. Irritation is absent or minimal. The most common experiences involve pain and weakness when externally rotating and elevating the arm.

Advanced Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain:

Advanced RCRSP represents the end-stage scenario, typically featuring extensive and untreatable tears in the rotator cuff. This phase often brings about severe discomfort, swelling, and substantial pain. Engaging in active movements becomes notably painful in this advanced stage.

How long does the rehabilitation take?

To alleviate Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain, patients typically require a structured exercise-based program spanning 12 to 24 weeks dependent on the irritation level and for how long they have had pain/discomfort for. This treatment approach involves targeted exercises and therapeutic activities aimed at addressing the underlying issues that you un-cover during the assessment.

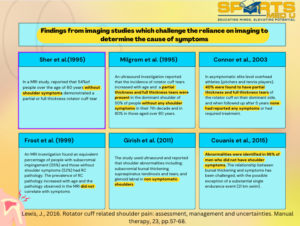

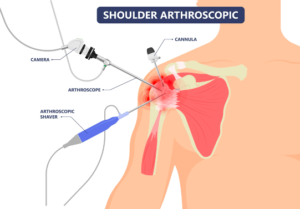

Role of Imaging

In diagnosing Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain, the most reliable tests are commonly recognized as ultrasound (US), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and direct observation during surgical procedures.

However, the presence of structural issues in many individuals without symptoms challenges the validity of US, MRI, and surgical observation as definitive reference tests. This absence of a true ‘gold-standard’ reference means that many individuals experiencing shoulder symptoms and receiving a diagnosis based on clinical orthopaedic assessments or imaging methods might be provided with inaccurate diagnoses.

It’s noteworthy that the observed symptom improvement might be attributed more to the enforced rest and step-by-step rehabilitation facilitated by the surgery, rather than the surgery itself. Thus, non-operative management for at least 6 months would be advisable before considering surgery.

Nonetheless,

Success rates ranging from 70% to 90% for favourable outcomes have been documented after Subacromial Decompression (SAD) surgery.

After the surgical procedure, a prolonged period of decreased activity and gradual reintegration into functional tasks is necessary, which could extend over several months. Recovery protocols post-surgery typically emphasize cautious and gentle movements during the initial stages of rehabilitation, especially if there has been a Rotator Cuff repair.

Research from Australia and the United Kingdom reveals:

- That non-manual labourers such as office workers may require around 6 weeks of rehab

- Whereas manual labourers such as construction workers might need approximately 3 months before resuming work, with an avoidance of driving for up to 4 weeks.

Risk factors for developing rotator cuff pain and why?

- Genetics: Genetic factors may influence the composition and strength of the rotator cuff tendons, potentially making them more susceptible to degeneration and injury.

- Hormonal influences: Hormones such as oestrogen might affect the structural integrity of the rotator cuff tendons, potentially contributing to their weakening and increasing the risk of injury

- Lifestyle factors such as smoking and drinking: Smoking and excessive alcohol consumption can impair blood flow and tissue healing, which may compromise the health of the rotator cuff tendons and contribute to their degeneration.

- Diabetes: It can negatively impact tissue health and healing processes, potentially making the rotator cuff tendons more vulnerable to damage and slower to recover.

- Excessive overhead movements (painters, swimmers): Repetitive overhead activities place strain on the rotator cuff tendons, potentially leading to overuse injuries and gradual degeneration over time. > 50 years of age: Age-related changes in tissue quality and blood supply can make the rotator cuff tendons more susceptible to degeneration and injury as individuals get older

Summary of article

The rotator cuff serves to stabilize the humeral head during shoulder movement, its muscles performing distinct actions.

Over 3 million people annually seek help for shoulder pain, often attributed to rotator cuff disease. Understanding the anatomy, including the roles of supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis, is vital.

Assessment of the unified rotator cuff structure is challenging. Contrary to the acromial irritation theory, evidence suggests tears occur within the tendon due to degeneration.

Rotator cuff-related shoulder pain results from degeneration, overuse, and structural changes, causing microscopic tears, stress, and age-related alterations. Clinical presentation involves pain during rest, night, and activities such as arm elevation.

RCRSP types vary in irritability, from easily provoked pain to severe, untreatable tears. The clinical course for RCRSP management includes structured exercises over 12-24 weeks, aiming to address degeneration, improve stability, and alleviate pain.

Sources

- Lewis, J., 2016. Rotator cuff related shoulder pain: assessment, management and uncertainties. Manual therapy, 23, pp.57-68.

- Payne, L.Z., Altchek, D.W., Craig, E.V. and Warren, R.F., 1997. Arthroscopic treatment of partial rotator cuff tears in young athletes: a preliminary report. The American journal of sports medicine, 25(3), pp.299-305.

- Yamamoto, A., Takagishi, K., Osawa, T., Yanagawa, T., Nakajima, D., Shitara, H. and Kobayashi, T., 2010. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery, 19(1), pp.116-120.

Leave a Reply