Patellofemoral pain: A complex & challenging condition

In this article, we delve into the multifaceted realm of Patellofemoral Pain syndrome(PFP), a common, yet challenging musculoskeletal condition characterized by knee pain during weight-bearing activities (very broad).

It predominantly affects young athletes, particularly females, and presents a complex interplay of contributing factors, making it challenging to diagnose and treat effectively.

We explore the causes, epidemiology, clinical presentation, long-term outcomes, diagnostic methods, surgical interventions, and risk factors associated with PFPS, providing a comprehensive overview of this prevalent and persistent knee problem.

Lets dive in!

Key takeaways of the article

- Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome is prevalent in young athletes, particularly females, and can persist for years, potentially leading to long-term patellofemoral osteoarthritis.

- PFPS has multifaceted causes, including malalignment, muscular imbalance, and overactivity, making diagnosis and treatment challenging.

- Imaging is not necessary but can be used for diagnosis in specific situations, while surgery is considered a last resort when conservative treatments fail, with varying effectiveness.

- Anatomic and neuromuscular factors, as well as biomechanical issues during activities, contribute to the risk of developing PFPS.

- The severity of pain, duration of symptoms, and certain risk factors can predict poor outcomes for individuals with PFPS, highlighting the importance of early and accurate intervention

What is Patellofemoral Pain syndrome?

PFPS is a musculoskeletal issue characterized by pain in the front and rear areas around the kneecap, worsening during weight-bearing activities with knee flexion, including

- Squatting

- Stair climbing

- Running

- Hopping

- Jumping

Additional diagnostic criteria comprise crepitus or grinding sensations during knee flexion, tenderness when palpating the patellar facets, minor effusion, and pain during sitting, rising from a seated position, or straightening the knee post-sitting

Fun Facts

- Patellofemoral pain pathophysiology is multifactorial.

- Fully diagnosis and treatment of PFP is challenging for healthcare providers.

- A 2013 study linked patellofemoral pain syndrome to decreased quality of life in athletes. It’s prevalent in young athletes participating in jumping, cutting, and pivoting sports.

- Up to 40% of knee-related clinical visits are attributed to patellofemoral pain

- PFP accounts for a significant portion of knee injuries, particularly in females.

- Common in basketball, volleyball, running, and other sports, affecting 13-26% of female athletes.

- Incidence is higher in adolescent females and young women compared to males.

- PFPS can limit physical activities and contribute to long-term patellofemoral osteoarthritis

Anatomy of the knee

Bones:

The knee joint is primarily formed by three bones:

- Femur: The upper thigh bone.

- Tibia: The larger of the two lower leg bones and the main weight-bearing bone.

- Patella: The kneecap, a small, flat bone that sits in front of the knee joint and protects it.

Ligaments:

Ligaments are tough, fibrous tissues that connect bone to bone and provide stability to the joint. In the knee, there are four main ligaments:

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL): Prevents the tibia from moving too far forward in relation to the femur.

- Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL): Prevents the tibia from moving too far backward in relation to the femur.

- Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL): Provides stability to the inner part of the knee.

- Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL): Provides stability to the outer part of the knee.

Meniscus:

The menisci are two wedge-shaped pieces of cartilage (fibrocartilage) that act as shock absorbers and provide cushioning between the femur and tibia. They also help distribute the load evenly across the joint.

Muscles:

Several muscles surround and support the knee joint, including the quadriceps (front thigh muscles) and the hamstrings (back thigh muscles). These muscles play a vital role in movement and stability.

The cause of Patellofemoral Pain

The causes of Patellofemoral Pain are multifaceted and encompass a complex interplay of factors, including malalignment, muscular imbalance, and overactivity.

Lets explore them in more detail

Malalignment

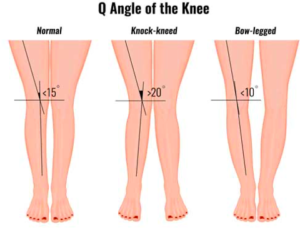

A prevalent cause of PFP, often involves several structural elements. These elements encompass increased Q-angle in weight-bearing positions, genu valgum (commonly referred to as knock-knees), tibia varum (which manifests as bow-leggedness), and patellar misalignment.

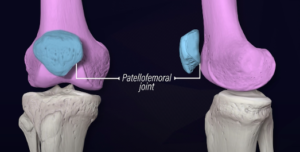

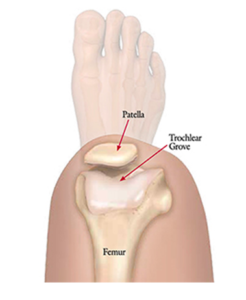

The patellar’s stability hinges on a few factors such as the alignment of the femur and tibia, the geometric characteristics of the patellofemoral joint, and the soft tissue constraints surrounding the patella. Within this context, the trochlear groove, a part of the knee joint, plays a critical role.

Notably, trochlear groove hypoplasia can lead to patellar instability, resulting in a cascade of problems, including patellar misalignment and potential chondromalacia patellae.

Muscular Imbalance

Another key contributor to PFP. This imbalance often involves a reduction in muscle volume and strength within the quadriceps, with particular emphasis on the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) muscle.

Studies have indicated discrepancies in VMO volume and strength when compared to the unaffected limb. Furthermore, delayed VMO activation relative to the vastus lateralis has been observed.

Beyond the quadriceps muscles, trunk biomechanics also play a pivotal role in the patellofemoral tracking. For instance, weaknesses in eccentric hip abduction and hip external rotation can lead to increased hip adduction and internal rotation during movements.

This dynamic imbalance places greater demands on the quadriceps, potentially increasing patellofemoral joint compression, exacerbating patellar maltracking, and potentially accelerating the onset of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis.

Overactivity

It represents a significant contributor to PFP, with the condition most prevalent among young, active individuals. A rapid escalation of activity, such as intensive athletic conditioning or military training in adults, has also been linked to the development of PFP. Notably, a study on infantry recruits showcased a high incidence of PFP that intensified as they underwent standard military training

The Frequency | Epidemiology of PFP

Incidence and Prevalence:

PFP is recognized as a common knee condition, causing discomfort around the kneecap. However, precisely pinpointing its annual occurrence (incidence) and the overall prevalence remains a challenge.

PFP can affect a wide spectrum of individuals. From active children to sedentary elderly individuals, PFP does not discriminate based on age.

Interestingly, there’s a notable surge in the prevalence of PFP among a specific group: young, active adolescents between the ages of 12 and 18. These adolescents often present in outpatient clinics with complaints of chronic anterior knee pain, which is typically associated with sporting activities.

Moreover, it’s important to highlight that PFP also has a significant presence among active adults, often humorously referred to as “weekend warriors,” as well as young military recruits. The condition appears to be intertwined with physical activity levels.

Gender Differences:

Research has uncovered an intriguing gender disparity in PFP. Several epidemiological studies have consistently reported a higher incidence of PFP among female patients. This observed female predominance varies, but some estimates suggest that women might experience an annual incidence of PFP that is up to two times higher than that in men.

To put it in perspective, in a recent study involving military recruits, the annual incidence of PFP was found to be 33 cases per 1000 person-years for female participants, while male participants had an incidence of 15 cases per 1000 person-years. This means that women are 2.23 times more likely to develop PFP.

Symptoms & Clinical presentation of PFP

Patients with Patellofemoral Pain commonly report the following:

- Symptoms tend to worsen during specific activities such as climbing stairs, descending stairs, squatting, running, or prolonged sitting.

- PFP is characterized by diffused, poorly localized discomfort cantered around or behind the patella (kneecap). The pain is often experienced during activities mentioned above.

- When asked to indicate the location of pain, patients may gesture by placing their hands over the front of the knee or drawing a circular motion with their fingers around the patella, a gesture referred to as the “circle sign.”

Onset and Nature of Symptoms:

- Typically, symptoms develop gradually over time, although in some cases, they may suddenly appear due to trauma or injury.

- Patients frequently describe the pain as an ache, though it may also be described as sharp, dependent on severity. This pain can be unilateral (affecting one knee) or bilateral (affecting both knees).

Additional Symptoms:

- Stiffness: Some patients may report stiffness or discomfort during prolonged sitting with the knees bent. This is referred to as the “theater” or “moviegoer” sign.

- Sensations of Instability: Patients occasionally mention a sensation of the knee giving way or buckling. This sensation may result from the pain’s inhibitory effect on the quadriceps muscle contraction. However, it should be distinguished from instability arising from patellar dislocation, subluxation, or ligamentous knee injuries.

- Popping or Catching Sensations: Some patients may describe feelings of popping or catching within the knee. Importantly, joint locking is not a typical feature of PFP, and it often implies the presence of a meniscal tear or a loose body within the joint.

- Swelling: While mild swelling may occasionally occur, it is uncommon to observe significant joint effusion.

Sign up to our newsletter and get break down of the latest research: Link

Mechanism of injury

Patellofemoral pain is complex and thus various biomechanical, behavioural (overuse) and anatomical factors contribute to its development.

It is predominantly thought of as an overuse injury, meaning that an increase in frequency, intensity and/or duration of exercise without adequate rest or preparation period is the driver of developing PFP.

In terms of origins, PFP is influenced by various biomechanical factors. These conditions often occur during activities involving abrupt movements, landing, or deceleration in sports.

Studies have identified several biomechanical variables contributing to PFP. The most significant factors involve the frontal plane mechanics of the knee. Excessive knee abduction loading and shallow knee flexion angles are common. During dynamic knee abduction, the ligaments and other knee structures are strained, primarily due to poor control of the hip musculature, leading to increased forces on the knee, and thus the patellofemoral joint.

These abnormal frontal plane mechanics can disrupt normal knee joint function, increasing the risk of PFP. Furthermore, inadequate hip control, including increased hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation, affects knee stability and contributes to knee valgus (abduction).

These hip mechanics may affect patellofemoral joint alignment and increase patellofemoral contact stress, leading to pain.

Ankle biomechanics, specifically reduced plantar flexion, may also play a role, as decreased ankle joint function can transfer excessive forces to the knee, potentially elevating injury risk.

PFP occurs due to a combination of factors involving the knee, hip, and ankle. Insufficient control, particularly in the frontal plane, muscle fatigue and altered knee and hip mechanics increase stress on the knee structures, ultimately contributing to the development of PFP.

Will patellofemoral pain ever go away? | Clinical course

Long-Term Outcome of Patellofemoral Pain (PFP):

Contrary to previous beliefs, current research indicates that Patellofemoral Pain is not a minor and self-limiting condition. Instead, it is a stubborn ailment that can persist for many years and has the potential to contribute to the development of long-term patellofemoral osteoarthritis. This risk is especially significant in cases where PFP begins in adolescence.

Predictors of Poor Outcomes:

Research has shown that the severity of pain and the duration of PFP symptoms are key indicators of a poor prognosis. In other words, if the pain is more intense, or if the symptoms persist for a longer time, it’s less likely that the patient will have a positive outcome.

Unfavourable Recovery Rates:

A significant portion of individuals dealing with PFP may not experience a favorable recovery even with various interventions. This means that the condition doesn’t always respond well to treatment, and outcomes can be disappointing for many people over a period of 12 months.

Duration and Pain Scale Score as Predictors:

One of the most consistent indicators of a poor long-term prognosis in PFP is the duration of the condition. If a person has been suffering from PFP for more than two months, it’s often a sign that their prognosis isn’t very optimistic.

Additionally, a score of less than 70 on the anterior knee pain scale is also associated with poor long-term outcomes.

The role of Imaging

Role of imaging in diagnosis of Patellofemoral Pain:

Diagnosis of PFPS is primarily based on clinical evaluation, and diagnostic imaging is often unnecessary.

However, radiography may be needed in specific situations, such as recent trauma, older patients (above 50) to check for patellofemoral osteoarthritis, skeletal immaturity, suspected bipartite patella, loose bodies, or when conservative treatment doesn’t yield improvement.

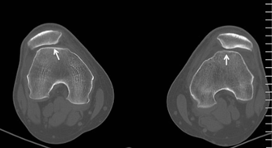

Radiography:

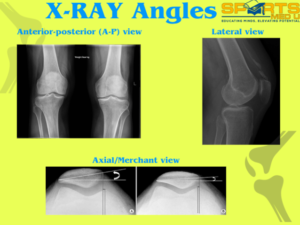

Radiography, like X-rays, complements clinical assessment but may not always correlate with symptoms. It’s crucial in cases with no improvement after conservative treatment, severe malalignment, or recent trauma.

Key radiographic views include weight-bearing anterior-posterior (A-P), lateral, and axial/Merchant views, with each offering valuable information about patellofemoral issues.

Advanced Imaging Techniques:

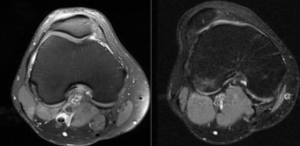

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are generally unnecessary for most PFPS cases. MRI is best for evaluating issues like malalignment, trochlear dysplasia, patella tilt, and chondral injuries.

It’s also useful for detecting loose bodies, stress fractures, and bone marrow changes indicating patellar subluxation or dislocation. MRI is particularly effective for assessing patellofemoral osteoarthritis, which manifests as cartilage loss, subchondral changes, edema, and cysts on imaging.

Surgery options for PFP

It’s typically considered a last resort for patellar femoral pian, only when nonoperative treatments fail to bring relief after 6 to 12 months. Surgery is warranted when there is a clear and specific problem that can be addressed surgically, such as an identifiable lesion or patellofemoral imbalance.

There are three general surgical options: realignment, resurfacing, and arthroplasty.

Realignment Procedures:

- Lateral Release: This minimally invasive procedure addresses a tight lateral retinaculum and lateral patellar tilt. Early knee motion is crucial to prevent postoperative stiffness.

- Medial Tibial Tubercle Transfer: This procedure can be successful in treating PFP, decreasing patellar load, and reducing postoperative stiffness. Full weight-bearing should be avoided for six weeks to allow for healing.

Resurfacing Procedures:

Procedures like autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI-C) or osteochondral transfers have mixed success in treating PFP, particularly when there’s cartilage damage in the patellofemoral joint.

Patellofemoral Arthroplasty:

Reserved for severe cases of osteoarthritic degeneration and may enable a return to some sporting activity with limitations.

Effectiveness:

Surgical interventions for PFP are challenging to assess due to limited controlled studies. Some studies showed that surgery didn’t significantly improve outcomes compared to conservative treatments.

As mentioned, surgery is usually the last option for PFP and may not be entirely effective. It’s generally considered for cases unresponsive to conservative treatment.

In selected cases with specific issues like severe malalignment, patella alta, or lateral patellar compression syndrome, surgery can yield good results. However, it’s important to be cautious as failure rates have been reported in a significant percentage of cases.

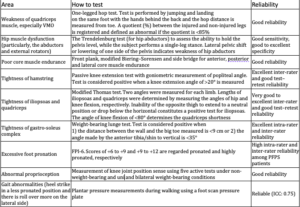

Risk factors for developing patellofemoral pain

Many studies have explored various factors that can increase the risk of developing patellofemoral pain. Prospective research has primarily focused on intrinsic factors, such as anatomic, neuromuscular, and movement-related issues, as these can be modified through rehabilitation to prevent the condition.

Variables like height, mass, body mass index, body fat percentage, age, and somatotype have been examined but aren’t significant risk factors for patellofemoral pain.

Anatomic Factors and Soft Tissue Restrictions:

Strong correlations have been found between anatomic factors (like soft tissue restrictions) and a higher risk of patellofemoral pain. For instance, tightness in quadriceps, hamstrings, triceps surae, and the iliotibial band has been linked to alterations in joint movement, which can increase stress on the patellofemoral joint.

Lower Extremity Alignment:

Issues like increased navicular drop and tibial torsion can also increase lateral patellofemoral joint stress due to altered lower extremity alignment.

Neuromuscular Function:

Patients with patellofemoral pain often exhibit neuromuscular issues, including muscle weakness in knee extensors, knee flexors, and hip abductors. Weak knee extensors can predict future patellofemoral pain and may lead to increased stress on the joint due to altered hip movement.

Glute Weakness Controversy:

There’s debate about whether glute (buttock) weakness is a cause or a symptom of patellofemoral pain. Either way, it’s a good place to start when objectively assessing.

A useful tool to measure strength is a hand held dynanometer

Biomechanics during Jump-Landing:

Studies have identified specific risk factors during functional activities like jump-landing tasks. For example, greater knee abduction moments during landing can increase the risk of developing patellofemoral pain, particularly in adolescent females

Summary of article

PFPS

- Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome causes knee pain during most weight-bearing activities

Causes

- PFPS has multifaceted causes, including malalignment, muscular imbalance, and overactivity.

- Anatomic and neuromuscular factors contribute to the risk of developing PFPS.

Epidemiology

- PFPS affects a wide range of individuals, from active pediatric patients to sedentary elderly individuals.

- Young, active adolescents are particularly prone to PFPS.

- Women have a higher incidence of PFPS compared to men.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

- Symptoms worsen during specific activities, including climbing stairs, running, and squatting.

- Patients experience diffuse knee pain, stiffness, and sensations of instability.

Clinical Course and Long-Term Outcomes

- PFPS is not always a minor or self-limiting condition and can persist for years.

- The severity of pain and duration of symptoms are key predictors of poor outcomes.

- Recovery rates can be unfavourable for some individuals.

Role of Imaging in Diagnosis

- PFPS diagnosis primarily relies on clinical evaluation.

- Imaging, such as radiography and advanced techniques, is used selectively when conservative treatment does not help.

Surgical Interventions

- Surgery is considered a last resort when conservative treatments fail.

- Surgical procedures include realignment, resurfacing, and arthroplasty.

- Surgery’s effectiveness varies, and it is generally reserved for specific cases.

Risk Factors for Developing PFPS

- Various factors, including anatomic and neuromuscular elements, increase the risk of PFPS.

- Biomechanical factors during activities like jump-landing can contribute to PFPS

Sources

- de Oliveira Silva, D., Pazzinatto, M.F., Del Priore, L.B., Ferreira, A.S., Briani, R.V., Ferrari, D., Bazett-Jones, D. and de Azevedo, F.M., 2018. Knee crepitus is prevalent in women with patellofemoral pain, but is not related with function, physical activity and pain. Physical Therapy in Sport, 33, pp.7-11

- Dischiavi, S.L., Wright, A.A., Tarara, D.T. and Bleakley, C.M., 2021. Do exercises for patellofemoral pain reflect common injury mechanisms? A systematic review. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 24(3), pp.229-240.

- Farzin Halabchi, Maryam Abolhasani, Maryam Mirshahi & Zahra Alizadeh (2017) Patellofemoral pain in athletes: clinical perspectives, Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine

- Rothermich, M.A., Glaviano, N.R., Li, J. and Hart, J.M., 2015. Patellofemoral pain: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment options. Clinics in sports medicine, 34(2), pp.313-327.

- Weiss, K. and Whatman, C., 2015. Biomechanics associated with patellofemoral pain and ACL injuries in sports. Sports medicine, 45, pp.1325-1337.

Leave a Reply