Managing Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS)

Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS) is a condition that plagues many individuals, often causing discomfort and hindering daily activities. One of the key diagnostic features of GTPS is the presence of point tenderness, commonly known as the “jump sign,” localized around the greater trochanter.

This article delves into the assessment techniques employed to identify GTPS, from pinpointing tenderness to reproducing pain through specific movements. While a precise diagnostic criterion for GTPS remains elusive, a thorough examination can provide valuable insights for recognition and evaluation.

Additionally, we explore various non-pharmacological and exercise-based management strategies to help those dealing with GTPS find relief and regain their quality of life

To learn more about what it is, risk factors and anatomy visit our article about GTPS

5 Key takeaways of the article

- Distinct Examination Features: Individuals with Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS) show point tenderness and the “jump sign” in the posterolateral region of the greater trochanter.

- Pain Reproduction Movements: Pain is often replicated through movements like hip abduction and external rotation, highlighting the presence of GTPS. Diagnostic

- Criteria and Palpation: Although specific diagnostic criteria for GTPS are lacking, the ability to reproduce pain through palpation is a common diagnostic indicator.

- Single Leg Stance Test: Pain manifestation during approximately 30 seconds of single-leg stance offers insight into the condition’s response under load-bearing conditions.

- Adjustments for Acute Management: Patients with GTPS can benefit from adjustments in their activities to reduce strain on the gluteal tendon, including side-lying and sleep posture, sitting posture, and careful weight distribution while standing.

Physical Assessment Of GTPS

Point Tenderness and Location:

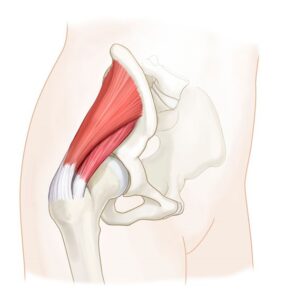

During a physical examination of individuals with GTPS, a distinct feature is the identification of point tenderness, often referred to as the “jump sign.” This tenderness is typically detected in the posterolateral region of the greater trochanter.

It may manifest either precisely at the site where the gluteus medius tendon attaches or slightly higher, positioned over the insertion point of the gluteus minimus tendon. This insertion point is situated on a ridge found laterally to the anterior triangular area of the greater trochanter.

Pain Reproduction through Movements:

To replicate the pain experienced by individuals with GTPS, specific movements are employed during the examination.

Active resistance of

- Abduction

- External rotation of the hip joint

These movements can often bring about the reproduction of pain.

Occasionally Movement of

- Internal rotation can also trigger pain

However, hip extension does not reproduce pain. If there’s pain with extension there might be something different masquerading as lateral hip pain, for example, a hamstring strain.

Diagnostic Criteria and Palpation:

It’s worth noting that there exists a lack of well-defined and specific diagnostic criteria for GTPS.

One of the most common findings during the examination is the ability to reproduce pain through palpation of the greater trochanteric region. This palpation-based approach is widely used as a diagnostic indicator.

Pain Reproduction during Single Leg Stance:

Another noteworthy aspect is the observation of pain reproduction after approximately 30 seconds of single-leg stance.

This particular test helps assess the extent to which the condition manifests under load-bearing circumstances.

The physical examination of individuals with GTPS reveals distinct patterns of tenderness and pain reproduction. Whilst specific diagnostic criteria might be lacking, the careful observation of these characteristic signs aids in the recognition and evaluation of the condition.

Early Management – Activity Modification

When dealing with GTPS , it could be beneficial to implement specific changes in patients activities to alleviate strain on the gluteal tendon.

Here are some practical adjustments to consider:

Side Lying and Sleep:

Advise patients to avoid lying on the side that’s causing pain. During sleep, if they lie on the opposite side, suggest placing a pillow between their legs. This can help minimize any excessive stretching of the tendon.

Sitting Posture:

Encourage patients to refrain from sitting with their legs crossed in a deeply flexed position for extended periods. This simple adjustment can assist in preventing undue pressure on the affected area.

Stretching Considerations:

If the patient has tight muscles, recommend temporarily skipping stretches that target the Piriformis and IT band. These stretches could potentially worsen the condition and should be avoided.

Weight Distribution When Standing:

Guide patients to be aware of how much time they spend putting weight on one foot while standing. It’s beneficial to reduce this habit, as it can lead to strain on the gluteal tendon.

Monitoring Step Count:

Instruct patients to monitor their step count and identify any patterns that trigger or worsen their symptoms. Suggest gradually increasing the steps while being attentive to any discomfort that arises.

Stair Use:

When using stairs, propose that patients hold the railing on the opposite side of the affected hip. This practice helps distribute the load more evenly and minimizes stress on the tissues.

Running Cadence:

For patients who are runners, recommend a slight increase in their running cadence (number of steps per minute) by approximately 5-10%. This adjustment can reduce hip adduction and potentially alleviate strain on the affected area.

Other Treatments To Consider

Non-steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Recent literature emphasizes the potential role of NSAIDs in treating tendinopathy, as it often involves inflammation. NSAIDs might have a place in the treatment of chronic tendinopathy. A retrospective case study by Sarno et al indicates that topical NSAIDs offer benefits similar to oral NSAIDs for GTPS within six weeks.

Corticoid Steroid Injection (CSI)

Corticoid steroid injection (CSI) provides short-term relief for GTPS. Studies suggest notable initial improvement within three months, peaking around six weeks.

However, symptoms can recur over the long term. While evidence on medication choice, dose, and frequency of CSI(s) is limited, higher doses of local corticosteroids tend to yield greater improvement.

Using CSI strategically alongside physiotherapy can reduce pain, but potential long-term tendon structure weakening is a concern. Minor side effects like skin depigmentation and post-injection pain are common, while serious adverse effects are rare.

Shockwave Therapy (SWT)

SWT is effective for tendinopathy, including GTPS. Its mechanism in influencing GTPS remains uncertain, but it likely stimulates healing processes via increased cellular activity and blood flow. Evidence for SWT in GTPS is moderately methodologically sound. Low-energy SWT proves effective for chronic GTPS, with improvements sustained for up to 12 months.

Foot Orthotics

Customized foot orthotics are explored as a treatment avenue. In a study comparing them to CS injection for trochanteric bursitis lasting under three months, the orthotic group had a 90% recovery rate at four months, compared to 40% in the injection group. Customized orthotics potentially offer better improvement than CSI alone for trochanteric bursitis. This study has methodological weaknesses, and limited research addresses orthotic interventions for GTPS.

Exercise based management

Research indicates that individuals who are dealing with gluteal tendinopathy tend to exhibit reduced strength in their hip abductor muscles. Given this, it’s advisable to place emphasis on exercises that target these abductor muscles.

As the patient progresses in the rehabilitation journey, you can gradually incorporate single-leg exercises into their routine, but remember to do so when it’s appropriate for their symptoms and level of recovery. This approach helps to address the specific weakness associated with gluteal tendinopathy while gradually advancing their exercise regimen.

Exercises based on difficulty:

- Easy

- Short side plank

- Side lying hip abduction

Medium:

- Standing hip abduction

- Banded clamshell

Hard:

- Side plank

- Banded side lying hip abduction

Isotonic exercise examples

- Side steps w/ band on knees (medium) – side step w/ band on ankles (hardest)

- Start w/ double leg functional – squats, bridge, deadlift – and progress to their single leg variences

Eccentric exercise consideration

Eccentric exercise stands out as a superior approach compared to generic exercises in addressing tendinopathies like gluteal tendinopathy. it not only reduces pain but also holds promise in restoring normal tendon structure.

While no direct studies on eccentric exercise effects in gluteal tendinopathy were found, research in related tendinopathies such as patellar and Achilles tendinopathy underscores its effectiveness.

Despite the absence of specific gluteal tendinopathy studies, the positive outcomes in similar conditions suggest potential benefits. This highlights the need for further research to comprehensively explore the of eccentric type load role in managing gluteal tendinopathy and optimize its application for effective rehabilitation.

Here are a few exercises you may want to consider

Eccentric Hip Abduction with Resistance Band:

Attach a resistance band to a sturdy anchor and loop the other end around your ankle. Stand sideways to the anchor, lift the leg away from the anchor, and then slowly lower it back down in a controlled manner.

Eccentric single leg Squats:

Perform squats by slowly lowering yourself down to a seated position and then using your unaffected leg to stand back up. This controlled lowering phase engages the hip abductors eccentrically.

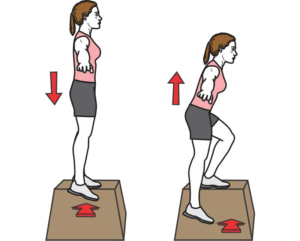

Eccentric Step-downs:

Step onto a raised platform using your affected leg, then use your unaffected leg to assist you in returning to the starting position. The emphasis is on the controlled descent.

Eccentric Side-Lying Leg Lifts:

Lie on your unaffected side and lift the affected leg slowly as high as you can, then lower it back down with control. This targets the hip abductors eccentrically.

Guidelines From NICE

The guidelines presented are the recommendations from NICE. Below information is a short summary. For a more in depth look, visit NICE website

Overview

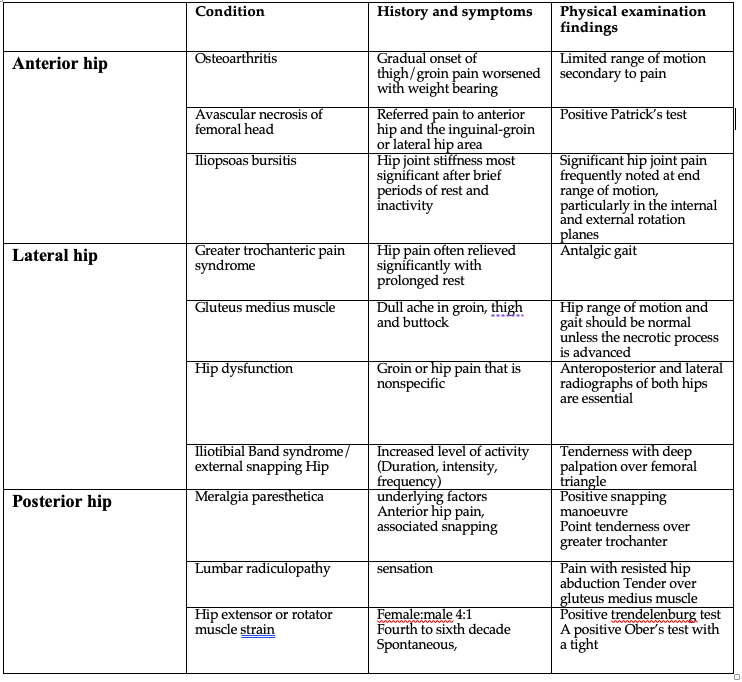

- A regional pain syndrome characterized by chronic intermittent pain around the greater trochanter (the bony prominence on the hip’s side).

- Previously termed ‘trochanteric bursitis,’ now referred to as ‘greater trochanteric pain syndrome.’

- Inclusive term preferred due to lesser role of trochanteric bursae and not always present inflammation.

Causes and Characteristics

- Caused by inflammation or physical trauma in muscles, tendons, fascia, or bursae.

- More prevalent in women, particularly aged 40–60 years.

- Often coexists with conditions like low back pain, knee osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia.

- Over 90% recover with conservative treatments like rest, pain relief, physiotherapy, or corticosteroid injection.

- Poorer outcomes tied to higher initial pain, longer duration, movement restriction, functional impairment, and older age.

Diagnosis and Core Features

- Clinical diagnosis based on lateral hip pain worsened by activity and tenderness near greater trochanter.

- Assess pain’s location, radiation, nature, onset, aggravating/relieving factors.

- Examine point tenderness and pain upon tension of trochanter-attached muscles and tendons.

- Rule out alternative diagnoses like sports hernia, osteoarthritis, nerve root compression, or bursa infection.

Initial Management

- Reassure about self-limiting nature of condition.

- Advise avoiding exacerbating activities and suggest ice pack use.

- Offer pain relief like paracetamol or ibuprofen if needed.

- Provide guidance on weight loss and smoking cessation if relevant.

Further Treatment

- If conservative approaches insufficient, consider corticosteroid injection and physiotherapy.

- Emergency referral needed for systemic symptoms, signs of infection, malignancy suspicion, weight-bearing issues, falls.

- Urgent orthopaedic referral for severe pain and persistent loss of function.

- Refer to orthopaedics for under-40s with unresponsive hip pain or painful, stiff hip affecting daily life after 3 months of physiotherapy.

Other Conditions To Be Aware of

Lateral hip pain extends beyond bursal inflammation and gluteal tendinopathy to encompass a range of potential sources such as gluteus medius muscle dysfunction, iliotibial band syndrome, osteoarthritis and lumbar spine disorders.

Specific causes of Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome include repetitive activities, sudden trauma, crystal deposition, and infections like tuberculosis. When confronted with acute trauma or identified risk factors, an added layer of caution is advisable.

This precaution is vital to differentiate GTPS from more severe conditions like femoral neck stress fractures or avascular necrosis that exhibit similar symptoms. A thorough understanding of these varied underlying factors aids in precise diagnosis and tailored treatment strategies for effective management

Summary Of Article

Assessment:

- Distinct feature of Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS) is point tenderness, known as the “jump sign.”

- Tenderness is typically located in the posterolateral region of the greater trochanter.

- Tenderness can occur precisely where the gluteus medius tendon attaches or slightly higher.

- Specific movements, like hip abduction and external rotation, can reproduce pain.

- Internal rotation may also trigger pain.

- Pain during hip extension might suggest an alternative condition.

Diagnostic Criteria and Palpation:

- Lack of well-defined diagnostic criteria for GTPS.

- Reproduction of pain through palpation of the greater trochanteric region is commonly used for diagnosis. Pain

Reproduction during Single Leg Stance:

- Pain can be reproduced after about 30 seconds of single-leg stance.

- This test assesses pain manifestation under load-bearing conditions.

Acute Management – Activity Modification:

- Adjustments to activities can alleviate gluteal tendon strain.

- Recommendations include side lying and sleep posture, sitting posture, stretching considerations, weight distribution when standing, monitoring step count, stair use, and running cadence adjustment.

Other Treatment Approaches:

- Non-steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) can be effective for treating tendinopathy, including GTPS.

- Corticosteroid injections provide short-term relief for GTPS.

- Shockwave Therapy (SWT) is effective for tendinopathy, including GTPS.

- Customized foot orthotics are explored as a treatment avenue.

- Exercise-based management targeting hip abductor muscles is recommended.

Eccentric Exercise Consideration:

- Eccentric exercises are superior for tendinopathies like GTPS.

- Positive outcomes in similar conditions support the effectiveness of eccentric exercises.

- Few specific gluteal tendinopathy studies, highlighting the need for further research.

Guidelines:

- GTPS is a regional pain syndrome around the greater trochanter.

- Diagnosis is based on clinical assessment, lateral hip pain worsened by activity, and tenderness near the greater trochanter.

- Initial management includes rest, pain relief, and physiotherapy.

- Further treatment options include corticosteroid injection and physiotherapy.

- Consider alternative diagnoses for lateral hip pain, as it can stem from various sources. The article provides insights into GTPS assessment, diagnosis, management, and alternative conditions causing lateral hip pain.

Sources

- Coombes, B.K., Bisset, L. and Vicenzino, B., 2010. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. The Lancet, 376(9754), pp.1751-1767.

- Ferrari, R., 2012. A cohort-controlled trial of customized foot orthotics in trochanteric bursitis. JPO: Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics, 24(3), pp.107-110.

- Rasmussen, K.J.E. and Fanø, N., 1985. Trochanteric bursitis: treatment by corticosteroid injection. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology, 14(4), pp.417-420.

- Rompe, J.D., Segal, N.A., Cacchio, A., Furia, J.P., Morral, A. and Maffulli, N., 2009. Home training, local corticosteroid injection, or radial shock wave therapy for greater trochanter pain syndrome. The American journal of sports medicine, 37(10), pp.1981-1990.

- Sarno, D., Sein, M. and Singh, J., 2015. (364) The effectiveness of topical diclofenac for greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a retrospective study. The Journal of Pain, 16(4), p.S67.

Leave a Reply