GTPS: Risk factors, Cause & Clinical Presentation

Are your patients grappling with unexplained hip discomfort? Delve into Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS) – a condition that often disguises itself as other sources of pain while primarily presenting as chronic hip discomfort.

Explore the underlying mechanics of GTPS, understanding how friction between the greater trochanter and iliotibial band triggers weakening of gluteal tendons. Uncover the risk factors contributing to this condition, including gender disparities, biomechanics, obesity, and lower back pain.

By the end of this article, you’ll be equipped with insights to confidently identify and manage GTPS, enhancing patient care and outcomes.

Learn how to assess & treat GTPS in our next article

5 Key takeaways of the article

- GTPS is chronic discomfort on the outer hip, often mislabeled as trochanteric bursitis, presenting mainly as pain without typical signs of inflammation.

- It affects 10-25% of industrialised societies, more common among females aged 40-60, and frequently coexists with hip joint osteoarthritis or low back pain.

- Involving trochanteric bursae, gluteal tendons, and muscles like gluteus medius, minimus, maximus, and tensor fasciae latae.

- GTPS stems from friction between greater trochanter and iliotibial band, causing tendinopathy and chronic pain, with symptoms including lateral hip discomfort, tenderness, and radiating pain.

- Treatment ranges from conservative approaches to surgery; risk factors include age, gender, obesity, lower back pain, and anatomical considerations like pelvic shape and angle.

What is Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome?

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS) is a chronic discomfort on the outer aspect of the hip. Formerly referred to as trochanteric bursitis, this specific pain condition often mimics pain arising from diverse sources such as myofascial pain, degenerative joint disease, and spinal problems.

However, labeling it as trochanteric bursitis might not be entirely appropriate, as the typical signs of inflammation like redness, warmth, and swelling are rarely present. Instead, pain remains the primary symptom.

Radiological findings in individuals with GTPS show varying prevalence rates. Bursitis, for instance, is observed in approximately 4% to 46% of cases, while gluteal tendinopathy ranges from 18% to 50% . Given this variability, the preferred clinical term for pain in the lateral hip region is greater trochanteric pain syndrome.

Fun Facts

- GTPS is estimated to affect between 10% and 25% of the population in industrialized societies

- It also affects between 1.8 and 5.6 patients per 1000 per year, more frequent between 40 and 60 years, predominantly female,and possibly related to pelvic biomechanics

- Approximately two thirds of individuals with GTPS have co-existing hip joint osteoarthritis or low back pain

- Gluteal tears are present in around 22% of elderly patients

The Anatomy

Bursae and Trochanteric Area

Bursae are fluid-filled sacs cushioning bony prominences and surrounding soft tissues. There is about 20 bursae in the trochanteric region. Additional bursae may develop due to excessive friction or increased hip offset.

Trochanteric Bursae and Lateral Hip Pain:

The trochanteric bursae on the lateral aspect of the greater femoral trochanter are often linked to lateral hip pain. Two main bursae are subgluteus maximus and subgluteus medius.

The subgluteus maximus bursa lies lateral to the greater trochanter. Positioned between the gluteus medius tendon and gluteus maximus muscle. Two types: superficial (within gluteus maximus) and deep (under fascia lata and gluteus maximus).

The greater trochanter serves as the main attachment site for strong abductor tendons.

The muscles and other tissues involved in lateral hip pain:

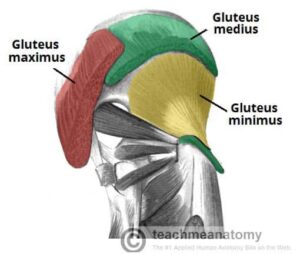

Gluteus Medius:

Origin: Outer surface of the ilium, between the posterior and anterior gluteal lines.

Insertion: Greater trochanter of the femur.

Function:

- Abduction: Initiates and maintains the movement of lifting the leg away from the midline of the body.

- Stabilization: Helps stabilize the pelvis during walking and standing, preventing the opposite hip from dropping when the opposite foot is off the ground.

Gluteus Minimus:

Origin: Outer surface of the ilium, between the anterior and inferior gluteal lines.

Insertion: Greater trochanter of the femur, beneath the gluteus medius.

Function:

- Similar to the gluteus medius, it assists in hip abduction and stabilization of the pelvis during movement.

Gluteus Maximus:

Origin: Posterior ilium, sacrum, and coccyx.

Insertion: Gluteal tuberosity of the femur and iliotibial band (IT band) attachment.

Function:

- Hip Extension: Responsible for assisting in straightening the hip joint, as in standing up from a seated position or moving the leg backward.

- Lateral Rotation: Participates in outward rotation of the thigh.

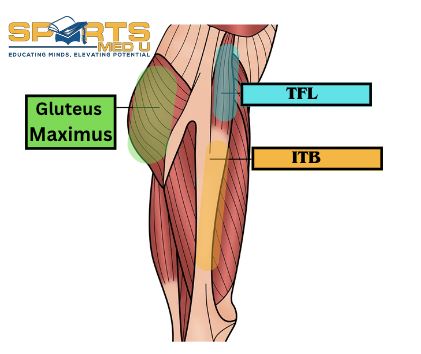

Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL):

Origin: Outer surface of the ilium, between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the iliac crest.

Insertion: Merges into the iliotibial band (IT band).

Function:

- Works in conjunction with the gluteus medius and minimus in hip abduction.

- It also tenses the IT band, aiding in stabilization of the hip and knee during movement.

Iliotibial (IT) Band:

Origin: Tensor fasciae latae muscle, which runs along the outer surface of the ilium.

Insertion: Lateral side of the tibia, just below the knee joint.

Function:

- Acts as a stabilizer during walking and running.

Origins Of The Condition

GTPS stems from repetitive friction between the greater trochanter and the iliotibial band. This friction inflicts small irritations on gluteal tendons connected to the greater trochanter, causing discomfort and weakening.

Local inflammation follows the friction, weakening tendons and increasing the load on the iliotibial band (ITB). This tightens the ITB, contributing to GTPS progression. Gluteal tendinopathy is a key cause of pain on the lateral aspect of thigh.

Tendinopathy involves chronic activity-linked pain and reduced tendon function, sometimes with swelling. It displays features like increased cells, more protein production, and new blood vessel growth, while inflammation remains absent.

Though repetitive activities play a role, tendinopathy can emerge without excessive overuse. The intricate connection between mechanical strain, cellular responses, and conditions like GTPS and gluteal tendinopathy underscores the multifaceted nature of their condition.

Frequency & Pattern- The Epidemiology

- Hip pain is a prevalent issue in the United States, with 10%–20% of adults aged 60 years or older reporting consistent hip pain that has been lasting for more than 6 weeks.

- About 2.5% of all sports-related injuries involve the hip.

- While hip pain can affect people of all ages, it is more commonly experienced between the fourth and sixth decades of life.

- Studies generally indicate a higher occurrence of hip pain in females (ratio of 3–4:1), although some studies do not show a clear gender preference.

- Interestingly, the presence of low back pain has been found to increase the likelihood of experiencing hip pain. With rates ranging from 20% to 35%. This suggests a significant link between GTPS and LBP in the musculoskeletal context.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of GTPS is pleasantly straightforward and can serve as a helpful guidepost for your diagnosis when you have the following cues in your spotlight.

Consider these clues to enhance your diagnostic prowess:

Presentation of Persistent Pain:

- Nature of Pain: GTPS typically manifests as continuous, chronic discomfort located in the lateral hip region and sometimes extending to the buttock.

Aggravating Factors:

- Pain intensifies when lying on the affected side

- Prolonged standing

- Transitioning to standing

- Sitting with the affected leg crossed

- Engaging in activities like climbing stairs or high-impact movements.

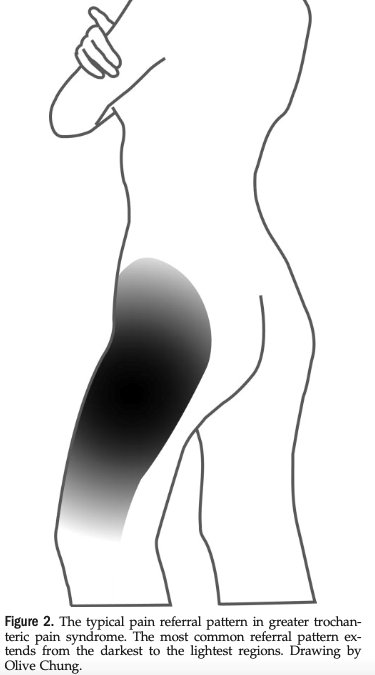

Radiating Pain Patterns: Radiation to Thigh and Knee:

- About 50% of GTPS patients experience pain radiating from the lateral hip to the thigh and sometimes reaching the knee.

- Tenderness at Greater Trochanter: Tenderness is noticeable along the lateral or posterior part of the greater trochanter.

- Groin and Lateral Thigh Pain: In some cases, pain might extend to the groin or along the lateral thigh, resembling lumbar disk herniation

Complex Pain Radiation Patterns:

- Diagnostic Challenges: Pain radiation patterns can complicate GTPS diagnosis due to overlapping anatomy with the iliotibial tract and certain lumbar dermatomes (L2–L4)

- Consideration of Other Structures: It’s important to note that pain radiating from various structures in the lumbar spine, such as zygapophysial joints, sacroiliac joint, intervertebral discs, and ligaments, can imitate trochanteric bursitis

Mechanism Of Injury

Just like many cases of tendon issues, GTPS is often caused by overuse. When you use certain muscles, like gluteus medius and minimus, too much without giving them enough rest, it can lead to inflammation and irritation. This is a potential pathway to GTPS, but there are other factors at play too.

In addition to overuse, direct impacts like falls or sports tackles can also cause irritation in the bursae or the bony area itself.

What’s interesting is that research on people with GTPS has given us more insight into the problems they face. We’ve found that their hip abductor muscles might be weaker, and they might struggle with controlling their movements when standing on one leg or walking. These issues can put extra strain on the tissues due to improper movement patterns.

Clinical course – When Will Patients get better?

Patients should be informed that GTPS may require 2 to 3 months, or possibly more, for full resolution. Ensuring patients are aware of this timeline is essential. It is advisable to promote both participation in physical therapy and adjustments to daily activities.

Imaging

Imaging isn’t very dependable and usually isn’t used to diagnose greater trochanteric pain syndrome . You can diagnose GTPS through the way the patient presents and the thorough physical examination; imaging isn’t typically necessary for diagnosis.

Surgery

Surgical intervention becomes a consideration when conservative treatments prove ineffective. At least 6 months of exercise and activity modification is recommended to before turning to the surgeon.

Gluteal Tendon Repair:

Gluteal tendon tears, often observed in the lateral section of the gluteus medius tendon, can arise due to trochanteric bursitis. These tears may present as partial, full thickness, or intrasubstance variations, often accompanied by symptoms such as hip abductor weakness and the Trendelenburg sign. The encouraging news is that gluteal tendon repair has demonstrated positive long-term outcomes, especially for refractory GTPS cases. Several studies highlight significant improvements and instances of patients becoming asymptomatic post-surgery.

ITB Release/Lengthening:

The iliotibial band (ITB) can contribute to pain and inflammation, leading to trochanteric impingement and subsequent bursitis. ITB release emerges as a pivotal treatment approach to alleviate these issues and prevent recurrence. ITB lengthening techniques, both proximal and distal, have showcased favourable long-term results. Various techniques, including Z-lengthening, cross-incision, and longitudinal release, have been employed with successful outcomes.

Trochanteric Bursectomy:

Endoscopic or arthroscopic trochanteric bursectomy has demonstrated positive outcomes over a span of at least two years post-surgery. While complications such as seroma and hematomas can arise, major post-operative issues are relatively infrequent. Notably, these findings hold promise, though a degree of caution is warranted due to the limited evidence hierarchy of some studies.

Considerations of the research results:

In assessing these surgical interventions for GTPS, it’s important to note that the evidence base often relies on single surgeon case series, retrospective studies, and the introduction of clinician-proposed techniques. However, what remains absent are level one or two studies. Consequently, future research, particularly prospective randomized controlled trials, is imperative to determine optimal intervention sites, preferred incision types, and the potential value of co-interventions, such as bursectomy, in the comprehensive treatment of GTPS.

Unravelling Risk Factors for GTPS

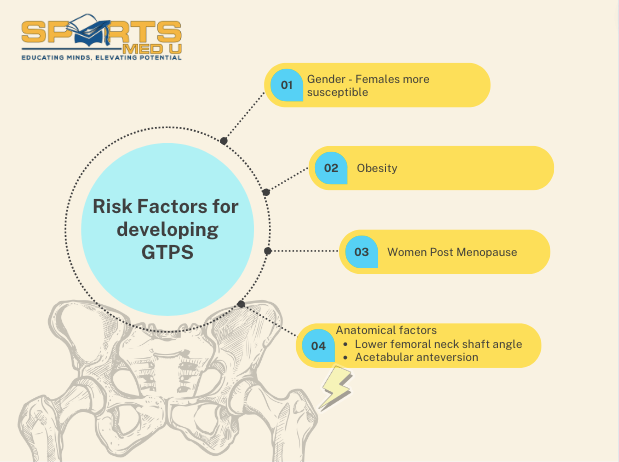

Multiple Influences on GTPS:

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is influenced by various risk factors, including age, gender, ipsilateral ITB pain, knee osteoarthritis, obesity, and lower back pain.

Gender and Biomechanics:

The higher prevalence of GTPS in women might be attributed to biomechanical differences stemming from variations in pelvic size, shape, and orientation (gynecoid vs. android) and their relationship with the iliotibial band (ITB). Females exhibit a greater pelvic width in proportion to their whole body, leading to more pronounced trochanters and elevated ITB tension over the trochanter.

Obesity’s Dual Impact:

Obesity emerges as a potential contributing factor due to its dual impact. The combined effects of increased stress on the hip joint, alongside hip and knee osteoarthritis and lower back pain, could heighten the risk of GTPS.

Post Menopausal Impact:

GTPS notably affects postmenopausal women, with substantial repercussions on daily function, sleep, and overall quality of life. The reasons behind this heightened prevalence in this specific demographic warrant further investigation. Anatomical Considerations:

Anatomical factors also play a role.

A lower femoral neck-shaft angle could predispose individuals to GTPS by intensifying the compression of the gluteus medius tendon against the greater trochanter. Similarly, increased acetabular anteversion might contribute to this condition

Summary of article

Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS):

- GTPS is a chronic discomfort in the outer hip region, once called trochanteric bursitis, but labeled as GTPS due to lack of typical inflammation signs.

Radiological Findings and Preferred Term:

- GTPS mimics various pain sources; radiological findings vary widely; bursitis (4-46%), gluteal tendinopathy (18-50%); “greater trochanteric pain syndrome” is the preferred term.

Key Facts about GTPS:

- GTPS affects 10-25% of industrialized society; 1.8-5.6 patients per 1000 yearly; common in ages 40-60, females, possibly linked to pelvic biomechanics.

- About two-thirds of GTPS patients have hip joint osteoarthritis or low back pain.

- Gluteal tears found in about 22% of elderly patients.

Anatomy and Muscles:

- Trochanteric area has about 20 bursae; main bursae are subgluteus maximus and subgluteus medius.

- Gluteus medius, minimus, maximus, TFL, IT band are the main culprits in lateral hip pain.

Causes, Symptoms, and Diagnosis:

- GTPS comes from friction between greater trochanter and iliotibial band, leading to tendinopathy and chronic pain.

- Symptoms include continuous lateral hip discomfort, tenderness, radiating pain patterns.

- Diagnosis involves patient presentation, physical examination; imaging isn’t often necessary.

Surgical Interventions:

- Surgical consideration after failed conservative treatment; gluteal tendon repair, ITB release/lengthening, trochanteric bursectomy are options.

- Gluteal tendon repair has positive outcomes for refractory GTPS cases.

- ITB release addresses trochanteric impingement and bursitis, with successful results.

- Trochanteric bursectomy through endoscopy or arthroscopy yields positive outcomes, though caution due to limited evidence hierarchy.

Risk Factors and Influences:

- GTPS influenced by age, gender, ITB pain, knee osteoarthritis, obesity, lower back pain. Higher prevalence in women attributed to pelvic biomechanical differences; obesity’s effects on hip and knee OA contribute to risk.

- Postmenopausal women are highly affected by GTPS, with its impact on daily function and quality of life

Sources

- Reid, D., 2016. The management of greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a systematic literature review. Journal of orthopaedics, 13(1), pp.15-28.

- Williams, B.S. and Cohen, S.P., 2009. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a review of anatomy, diagnosis and treatment. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 108(5), pp.1662-1670.

Leave a Reply