Cracking the Code of Frozen Shoulder: What You Need to Know

As physiotherapists, unravelling the complexities of adhesive capsulitis or otherwise known as frozen shoulder, is key. Let’s embark on a journey to demystify this condition and enhance our understanding.

In this article, we delve into the intricacies that trigger frozen shoulder, dissecting the contributing factors and shedding light on the risks our patients might face.

Join us as we navigate through frozen shoulder’s puzzle pieces – exploring its root causes, identifying risk factors, and recognising the tell tale symptoms.

Armed with this knowledge, we’ll be better equipped to guide our patients toward effective treatment and recovery strategies.

I will be using the terms frozen shoulder and adhesive capsulitis interchangeably.

Read our article on the assessment & treatment to learn more

5 Key takeaways of the article

- Adhesive capsulitis, or frozen shoulder, involves increasing pain and reduced shoulder movement, affecting the shoulder joint.

- The rotator interval and coracohumeral ligament are implicated in initiating frozen shoulder, with subsequent involvement of other joint capsule parts.

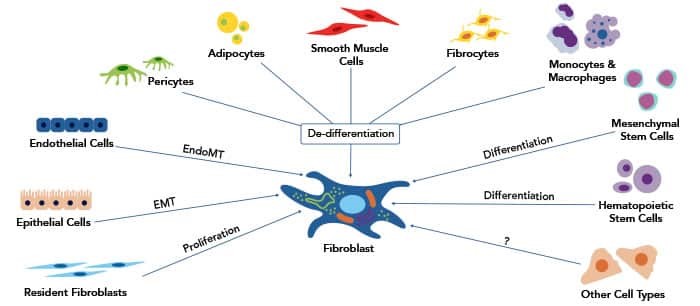

- Early inflammatory response in the shoulder leads to tissue changes, where fibroblasts and transforming growth factor-beta 1 contribute to tissue stiffness.

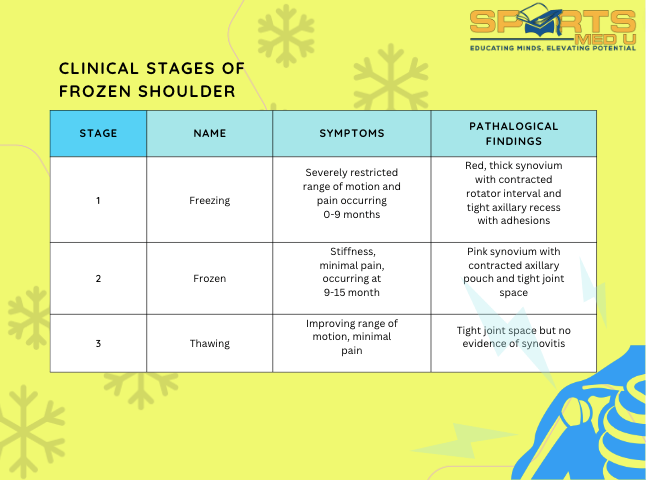

- Frozen shoulder progresses through freezing, frozen, and thawing phases, with variable timelines; while most cases resolve over time, some individuals experience prolonged symptoms or permanent disability.

Frozen Shoulder – What Is It?

Adhesive capsulitis, commonly known as frozen shoulder, is described in current practice guidelines as a type of pain condition that tends to get worse over time.

It’s specifically related to the shoulder joint.

This condition is characterized by not only increasing pain but also a reduction in the ability to move the shoulder both actively and passively. In other words, people with adhesive capsulitis experience a combination of pain and a noticeable decrease in how far they can move their shoulder on their own and when someone else helps move it.

What Tissue Is At Cause?

For quite some time, researchers have been suggesting that a particular area in the shoulder called the ‘rotator interval,’ along with a ligament known as the ‘coracohumeral ligament’, could be part of the underlying issues in frozen shoulder. This area and ligament might play a crucial role in how frozen shoulder develops. It’s believed that initially, the problems with the rotator interval and the CHL kickstart the process that leads to rozen shoulder.

As the condition progresses, other parts of the joint capsule become involved later on. In simpler terms, this suggests that the rotator interval and the CHL are like the starting point or a key player in the development of frozen shoulder, and other parts of the shoulder joint become affected as the condition advances.

Fun Facts

- Painful limited range of motion of the shoulder was first described as a clinical entity in 1872, when Duplay termed the phenomenon scapulo-humeral periarthritis

- This same phenomenon was termed frozen shoulder as early as 1934, by Codman, and is a colloquialism that is still in use today

- 1945 and introduced the term “adhesive capsulitis” to refer to a thickening of the glenohumeral joint capsule

- Adhesive capsulitis is thought to afflict between 2 and 5% of the general population, with women affected more frequently than men

Anatomy

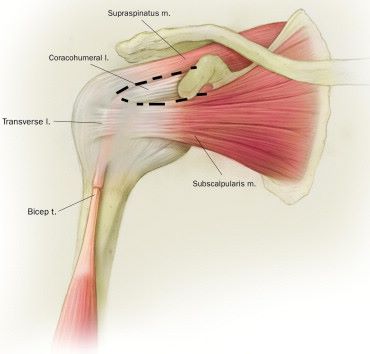

Rotator interval

The term ‘rotator interval’ refers to two triangular spaces that are like gaps within the covering tissue of the rotator cuff, which is a group of important muscles in the shoulder.

-

- The ‘anterior rotator interval’ is the bigger triangle located between the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons.

- The ‘posterior rotator interval’ is the smaller triangle between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons.

Imagine the rotator interval as a triangular space that’s bordered by the lower part of the subscapularis muscle, the upper front part of the supraspinatus muscle, and the base of the coracoid process. Inside this space, you’ll find something called the long head of the biceps tendon.

- The ‘roof’ of this space is formed by the coracohumeral ligament, the superior glenohumeral ligament, and the covering of the rotator interval.

- The ‘floor’ is the smooth cartilage on the upper part of the humerus bone. There’s a small fat pad called the subcoracoid fat triangle that fills the gap between the covering of the rotator interval, the CHL, and the coracoid process.

This rotator interval does an important job during shoulder movement. It provides support while the shoulder is in motion. When the integrity or strength of the rotator interval is compromised, it has been shown to contribute to problems like stiffening and instability in the shoulder joint.

In the simplest way possible, the rotator interval is a triangle-shaped space in the shoulder that contains important tissues like tendons and ligaments. It helps the shoulder move properly, and if it gets affected, it can lead to shoulder stiffness and instability.

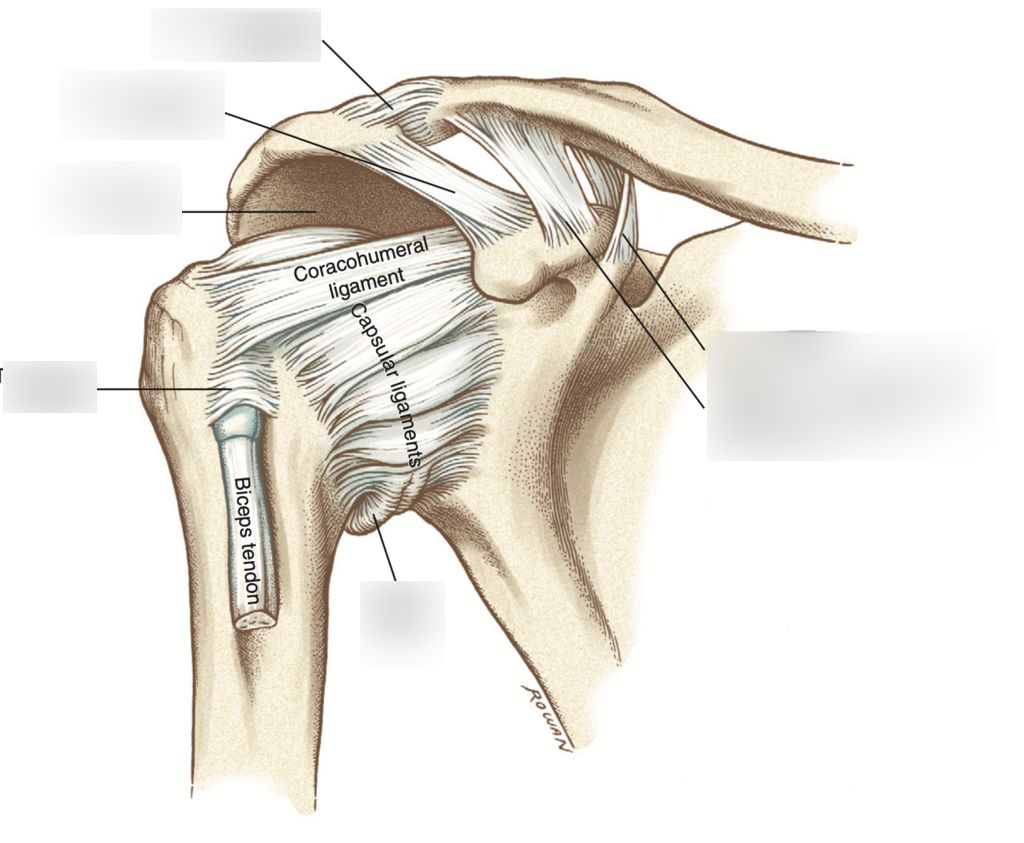

Coracohumeral ligament:

The coracohumeral ligament starts from the outer base of the coracoid process and has two parts.

- One attaches to the front of the supraspinatus tendon and greater tuberosity,

- The other connects to the upper subscapularis fibers, transverse humeral ligament, and lesser tuberosity.

The coracohumeral ligament helps prevent excessive inward movement of the upper arm bone during raising and outward rotation of the arm, becoming tighter in those positions to stabilize the shoulder. It relaxes when the arm is lowered and rotated inward

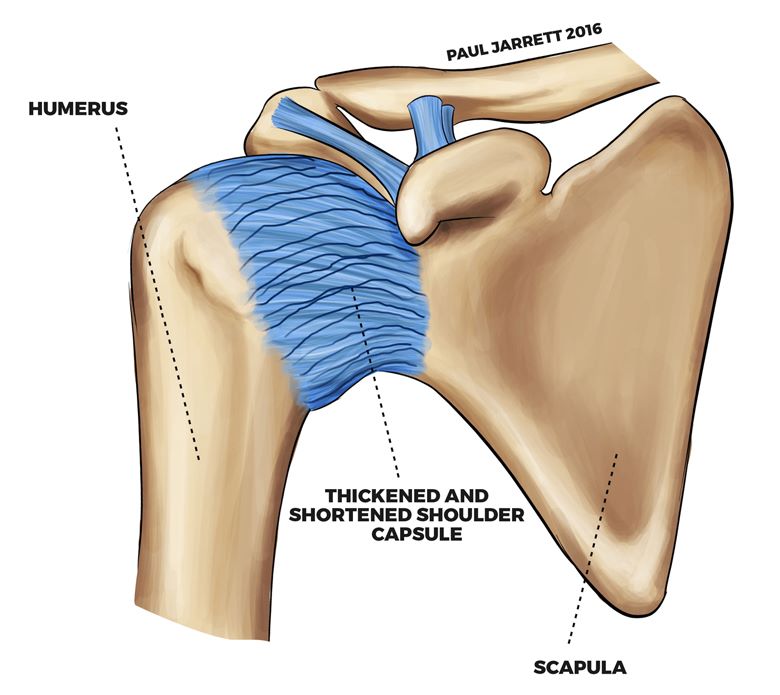

Shoulder capsule:

The shoulder joint capsule is a fibrous sleeve that surrounds and encases the articulating surfaces of the humeral head (upper arm bone) and the glenoid cavity (part of the scapula). It provides stability to the joint by holding the bones in place and preventing excessive movement.

It helps to protect the joint and its structures from injury by preventing the bones from dislocating or moving too far out of their normal positions.

Histology

In the early stages of the condition, there are changes happening inside the shoulder. There’s more blood flow and growth of tissue in the lining of the joint (synovium), which can lead to swelling and more cells (fibroblasts) being produced. This also causes new nerve fibres to form around small blood vessels.

These nerves are created because of a molecule called nerve growth factor receptor p75. Alongside this nerve growth, there are substances in the body that promote inflammation. These substances also make certain channels more sensitive to acid, which can contribute to increased pain sensitivity (hyperalgesia)

What Causes The Tissue Stiffening In Frozen Shoulder?

To make this simples lets get some definitions out of the way:

- Fibroblast = “A fibroblast is a type of cell that contributes to the formation of connective tissue, a fibrous cellular material that supports and connects other tissues or organs in the body. Fibroblasts secrete collagen proteins that help maintain the structural framework of tissue.” https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Fibroblast#:~:text=A%20fibroblast%20is%20a%20type,the%20structural%20framework%20of%20tissues

- Collagen = “Collagen is the most abundant protein in the body. Its fiber-like structure is used to make connective tissue.”

- TGF-β1 = “The TGFβ-1 protein triggers chemical signals that regulate various cell activities inside the cell, including the growth and division (proliferation) of cells, the maturation of cells to carry out specific functions (differentiation), cell movement (motility), and controlled cell death (apoptosis)”

- Myofibroblasts = “Myofibroblasts are contractile, α-smooth muscle actin-positive cells with multiple roles in pathophysiological processes. Myofibroblasts mediate wound contractions, but their persistent presence in tissues is central to driving fibrosis, making them attractive cell targets for the development of therapeutic treatments”

Fibroblasts play a crucial role in tissue health.

They’re not just responsible for making collagen, but they can also contract in the ‘soil’ around cells. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) not only helps these cells become more specialized (myofibroblasts), but it also promotes collagen production, leading to tissue stiffness.

However, tissue stiffness isn’t only caused by chemical signals like TGF-β1, its also caused by physical stress. Fibroblasts can ‘feel’ this stress through their internal structure. Interestingly, these cells need a certain level of stress to turn into myofibroblasts. Mechanical stress can activate hidden TGF-β1, adding to tissue stiffness. Both mechanical stress and TGF-β1 are closely connected and important factors in tissue stiffness.

Now, I know this might be difficult to digest, to make it easier think of TGF- β1 as cement.

Fibroblasts do more than make collagen – they can also contract. ‘Cement’ in the body helps them change and make collagen, making tissues stiff. Stiffness isn’t only from ‘cement’, it’s also from physical stress. Fibroblasts can sense this stress and need some of it to become specialized. Stress can also activate ‘cement’, making things stiffer. Both stress and ‘cement’ are key in tissue stiffness

An early inflammatory response at the onset of Frozen Shoulder

Definitions:

- Connective tissue = “Connective tissues bind structures together, form a framework and support for organs and the body as a whole, store fat, transport substances, protect against disease, and help repair tissue damage”

Traditionally, fibroblasts are recognized for their role in building and changing the ‘scaffolding’ of connective tissue. But they also act as watchful cells in the immune system, influencing the arrival and actions of immune cells. Recent studies indicate that an early immune response with too many inflammatory signals might trigger frozen shoulder, setting off a series of tissue changes. These signals can affect how fibroblasts grow, work, and change, disrupting collagen-building.

What Triggers The Onset Of Adhesive Capsulitis?

The exact cause of frozen shoulder remains uncertain, similar to many diseases. While microtrauma has been proposed as a trigger, evidence is limited. Increasingly, a low-level, long-lasting inflammation is considered significant for frozen shoulder development.

This can be caused by a number of factors like:

- Overuse, for a example frequent rotator cuff related shoulder pain(See Article) type problems

- Autoimmune condition such as rheumatoid arthritis, which attacks bodies own cells causing inflammation.

- Metabolic conditions such as diabetes or thyroid disorders are associated with systemic inflammation.

- Infection

- Genetics, some people may just be more susceptible to chronic inflammation in the joints.

- Hormonal imbalances, particularly in women during hormonal fluctuations such as menopause, can influence inflammation

Markers of chronic inflammation are elevated in patients suffering from this condition.

Conditions like diabetes and thyroid disorders, linked to inflammation, have a higher frozen shoulder risk. Even personality traits and depression, linked to inflammation, may contribute. Female hormones could play a role due to the higher incidence in perimenopausal women, but a direct link hasn’t been confirmed in current studies.

Why only the shoulder?

Throwing accurately and forcefully is a significant skill developed through human evolution, shaping the shoulder for energy storage and strong external rotation. In our modern sedentary lifestyle, the front of the shoulder capsule and ligaments might not get enough exercise or stretching due to reduced throwing and overhead actions.

This could make these structures more vulnerable to oxidative stress, linked to inflammation. Interestingly, manual laborers seem less prone to frozen shoulder, possibly due to more shoulder use. Also, the less-dominant side might be less affected. Although it’s not fully understood, the decline of myofibroblasts through apoptosis could explain the reversibility seen in frozen shoulder’s later stages, similar to how they vanish after wound healing.

The Pattern And Frequency Of Frozen Shoulder – Epidemiology

The exact epidemiology of frozen shoulder can vary based on factors such as:

- Age

- Gender

- Underlying health conditions.

The general overview of the epidemiology of frozen shoulder is as follows

De La Serna et al estimated that it affects around 2% to 5% of the general population. It most commonly occurs in individuals between the ages of 40 and 60, although it can occur at any age. Women are more commonly affected than men, with a reported female-to-male ratio of 2:1 to 3:1.

Symptoms & Clinical presentation

There are 3 main complaints you need to look out for to increase the suspicion of frozen shoulder:

- Frozen shoulder mainly affects the non-dominate hand, about 70% of the time

- Gradual onset of shoulder pain

- Gradual reduction in shoulder range of motion, especially external rotation and flexion

Clinical Course of Frozen shoulder

In adhesive capsulitis, the condition tends to naturally resolve itself over time. Typically, this process takes around 18 to 24 months. However, it’s important to note that some individuals may experience ongoing symptoms and movement limitations that extend beyond 3 years. Studies suggest that up to 40% of patients may fall into this category. Additionally, a smaller percentage, approximately 15% of patients, might unfortunately face permanent disability due to the condition.

The 3 phases

The frozen shoulder condition unfolds in three distinct phases:

Freezing Phase (Painful Phase):

- This initial phase, lasting approximately 10 to 36 weeks, is marked by significant pain.

Frozen Phase (Stiffness Phase):

- Following the painful phase, the frozen phase sets in, which typically spans 4 to 12 months. During this period, stiffness becomes a prominent issue.

Thawing Phase (Recovery Phase):

- Finally, the recovery phase takes place over about 5 to 24 months, during which a gradual improvement in symptoms and mobility occurs.

However, it’s important to note that these phases might not be the most accurate way to describe the condition for two reasons:

Natural History Misconception: Using these phases may mistakenly lead patients to believe that they will inevitably progress through them and eventually recover fully without any treatment. This can be misleading and discourage timely intervention.

Variable Symptoms: Some patients have reported experiencing varying degrees of shoulder symptoms for extended periods, ranging from 2 to 7 or more years after initial symptoms appeared. It’s crucial to understand that frozen shoulder progresses and heals slowly, necessitating patience throughout the recovery journey

Imaging

Adhesive capsulitis is usually diagnosed based on clinical findings. It aligns with the slow emergence of shoulder pain and restricted range of motion, particularly in external rotation and forward flexion.

Currently, imaging isn’t typically needed for diagnosing adhesive capsulitis. Instead, imaging is primarily utilized to rule out different sources of shoulder pain, like arthritis or issues with the rotator cuff or labrum.

Surgery

Surgical management of frozen shoulder, also known as adhesive capsulitis, is typically considered when conservative treatments have not provided significant relief or when the condition is causing severe pain and functional limitations. Surgery is usually reserved for cases that have not responded well to non-surgical approaches over an extended period. The surgical options for treating frozen shoulder include:

Arthroscopic Capsular Release:

Arthroscopic surgery is the most common surgical procedure used to treat frozen shoulder. It involves making small incisions and using a tiny camera (arthroscope) and surgical instruments to release the tight and contracted capsule around the shoulder joint. The surgeon cuts or releases the adhesions that are restricting shoulder movement. This procedure is less invasive than open surgery, which can help reduce recovery time.

Manipulation Under Anesthesia with Arthroscopic Capsular Release:

In some cases, manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) may be performed before or during arthroscopic capsular release. During MUA, the patient is put under anesthesia, and the surgeon manually moves the arm to break up adhesions and improve range of motion. This is often followed by arthroscopic capsular release to further release any remaining adhesions.

Open Capsular Release:

Open surgery involves making a larger incision to directly access the shoulder joint capsule and release the adhesions. While this approach provides better visualization and access, it is more invasive and typically requires a longer recovery period compared to arthroscopic surgery.

Rotator Interval Closure:

In some cases, a procedure known as rotator interval closure may be performed during arthroscopic surgery. The rotator interval is a part of the capsule that is often involved in adhesive capsulitis. Closing the rotator interval can help stabilize the shoulder and prevent future adhesions.

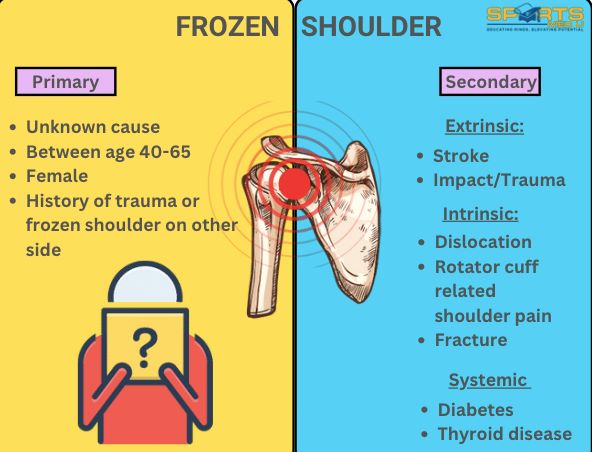

Risk factors

-

- Female gender is a factor. As mentioned before, it’s not fully known why, however, the hypothesis is that it is due to hormonal changes and women having more lax ligaments which makes them more susceptible to microtrauma and thus chronic inflammation

-

- Diabetes mellitus being a significant risk for adhesive capsulitis. In individuals with diabetes, there’s a higher prevalence of 13.4%, which is five times more than the general population. Additionally, about 30% of adhesive capsulitis cases involve diabetes.

-

- Other conditions like thyroid issues, rheumatological diseases, and certain medical factors like Parkinson’s, adrenal insufficiency, heart-lung problems, and previous trauma or surgery can also contribute to adhesive capsulitis, especially in secondary cases.

Summary of article

- Adhesive capsulitis, or frozen shoulder, is a painful condition affecting the shoulder joint, characterized by increasing pain and reduced shoulder movement.

- The “rotator interval” and “coracohumeral ligament” are believed to be involved in the development of frozen shoulder, with other joint capsule parts becoming involved as the condition progresses.

- Fibroblasts play a key role in tissue stiffness, producing collagen and responding to mechanical stress.

- Early inflammation and immune responses may trigger frozen shoulder, affecting fibroblasts and collagen building.

- Triggers for frozen shoulder include overuse, autoimmune conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), metabolic disorders (like diabetes), infections, genetics, hormonal imbalances, and oxidative stress.

- Symptoms include gradual onset of pain and reduced range of motion, primarily external rotation and flexion.

- Frozen shoulder follows three phases: painful, stiffness, and recovery phases.

- Surgical options are considered if conservative treatments fail, including arthroscopic capsular release and open capsular release.

- Risk factors include female gender, diabetes, thyroid issues, rheumatological diseases, Parkinson’s, adrenal insufficiency, and previous trauma or surgery

Sources

- De la Serna, D., Navarro-Ledesma, S., Alayón, F., López, E. and Pruimboom, L., 2021. A comprehensive view of frozen shoulder: a mystery syndrome. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, p.638.

- Fields, B.K., Skalski, M.R., Patel, D.B., White, E.A., Tomasian, A., Gross, J.S. and Matcuk, G.R., 2019. Adhesive capsulitis: review of imaging findings, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment options. Skeletal radiology, 48, pp.1171-1184.

- Hand, C., Clipsham, K., Rees, J.L. and Carr, A.J., 2008. Long-term outcome of frozen shoulder. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery, 17(2), pp.231-236.

- Kraal, T., Lübbers, J., van den Bekerom, M.P.J., Alessie, J., van Kooyk, Y., Eygendaal, D. and Koorevaar, R.C.T., 2020. The puzzling pathophysiology of frozen shoulders–a scoping review. Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics, 7(1), pp.1-15.

Leave a Reply