Achilles Tendinopathy: Everything you Need to know

Get ready to boost your expertise as we take a closer look at Achilles tendinopathy. We’ll break down the definition, symptoms, and risk factors of this condition, focusing on how they relate to physiotherapy practice. By the end of this article, you’ll have the background knowledge of Achilles tendinopathy and associated symptoms, enabling you to provide top-notch care to your patients. Let’s embark on this journey together, arming ourselves with the know-how to tackle Achilles tendinopathy head-on and elevate our physiotherapy practice. Let’s get started!

5 Key takeaways

- Achilles tendinopathy is a common condition causing posterior heel pain with both inflammatory and degenerative aspects, including insertional (20% of cases) in older adults and non-insertional (80% of cases) in younger, more active individuals.

- The Achilles tendon connects calf muscles to the heel bone, crucial for walking, running, and jumping, allowing plantarflexion of the foot and absorbing shock during physical activities to provide stability

- Inadequate warm-up, excessive exercise without progression, poor technique, muscle weakness, foot misalignment, gender (more common in males), and age (more common over 30) increase the risk of Achilles tendinopathy.

- Symptoms include stiffness, acute inflammation signs (swelling, redness), and a pain pattern of pain at the start of exercise that subsides with continued activity, with symptom duration helping classify the condition.

- Most people with Achilles tendinopathy can return to their sport within a year with proper mechanical loading, targeted exercises, and rest, while surgery is rare and considered for severe, unresponsive cases after conservative treatments, with imaging using ultrasound as the preferred modality in complex cases.

What is an achilles tendinopathy?

Achilles tendinopathy is a prevalent condition that affects the Achilles tendon, resulting in posterior heel pain. It has both inflammatory and degenerative aspects, leading to ongoing discussions within the medical community regarding its precise nomenclature (naming).

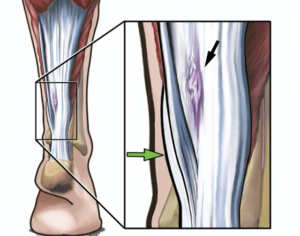

There are two distinct types of Achilles tendinopathy: the insertional form, accounting for 20% of cases, commonly observed in older, less active adults, and the non-insertional form, which constitutes 80% of cases and typically occurs along the tendon, approximately 2-3 cm above its insertion. The non-insertional type is more frequently seen in younger people who are more active.

Fun Facts

- The Achilles tendon is the strongest in the human body

- It is Subject to peak forces of 12.5 times the body weight when running at full speed

- In one study, 55% of 455 patients with Achilles tendon problems were runners, and 11% soccer players

- Incidence: The incidence of Achilles tendinopathy ranges from 7 to 9 per 1000 people per year. This means that approximately 0.7% to 0.9% of the general population will develop the condition each year.

Anatomy

The Achilles tendon is a thick, fibrous band of tissue that connects the calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus) to the heel bone.

Origin:

The gastrocnemius originates from the posterior aspect of the femur bone above the knee joint, while the soleus muscle originates from the posterior aspect of the tibia bone below the knee joint.

Insertion:

The two muscles merge together to form the Achilles tendon, which runs vertically down the back of the lower leg and inserts onto the calcaneus bone of the heel.

Function:

The Achilles tendon is essential for walking, running, and jumping, as it allows for plantarflexion of the foot, which is the movement of pointing the toes downwards. This movement is facilitated by the contraction of the calf muscles, which pull on the Achilles tendon and transmit the force of the muscle contraction to the heel bone, causing the foot to move. The Achilles tendon also helps to absorb shock and tension during physical activities, providing stability and support to the foot and ankle

Mechanism of Injury

It has been reported that training errors contribute to 60% to 80% of tendon overuse injuries in runners. It’s crucial to be aware of these errors to prevent or listen out in the subjective assessment. It’s common for patients to report:

- Running long distances (without adequate progression to such distance)

- Increasing intensity to quick and too soon

- Consistently training at high intensity without adequate rest periods

- Excessive amount of uphill/downhill running

Gradual progression, adequate rest, and varied terrain can help mitigate these risks.

Additionally, explosive movements like jumping and sprinting can stress the tendons. Proper warm-up, dynamic stretching, and strength training are essential to prepare the tendons for these activities. Moreover, direct impact to the Achilles tendon can cause injuries, so being cautious during physical activities is important.

The Clinical Presentation

As in any condition it’s crucial to understand the clinical presentation of Achilles tendinopathy to detect it early and prescribe intervention, which can prevent worsening of injury and potentially leading to more severe complications.

Secondly, knowing the specific symptoms helps in accurate diagnosis and allows to distinguish it from other similar conditions, enabling appropriate treatment planning.

Lastly, understanding the symptoms of Achilles tendinopathy helps guide patient education.

Here is what we need to look out for.

-

- Stiffness: Achilles tendinopathy usually manifests as pain and/or stiffness in the midportion of the tendon.

- Signs of acute inflammation: You will commonly observe local swelling, redness, or possible thickening of the tendon when comparing side to side. This indicates structural changes.

- Pain pattern: Patients typically report pain at the beginning of exercise when the tendon is loaded, which subsides with continued activity. However, if they persist with the activity, the pain can escalate and require them to stop. This pattern of pain during exercise is a hallmark symptom of Achilles tendinopathy.

The duration of symptoms helps classify the condition. Symptoms lasting less than two weeks are considered acute tendinopathy, while symptoms persisting for two to six weeks fall under subacute tendinopathy.

Chronic tendinopathy is diagnosed when symptoms extend beyond six weeks. This classification guides treatment planning and management decisions.

Clinical course

Around 80% of people who suffer from Achilles tendinopathy can return to their sport within a year, experiencing no pain. Mechanical loading plays a vital role in healing and recovery by promoting tendon tissue remodelling.

However, overloading the tendon without sufficient recovery can result in further damage. It is crucial to find the right balance between loading and recovery. As healthcare professionals, our main responsibilities are to educate patients on the importance of controlled loading through targeted exercises and gradual progression, while also emphasizing the need for rest and recovery periods.

Imaging

The frequency of imaging used to determine Achilles tendinopathy in a clinical setting can vary depending on the individual patient’s presentation and the results of the objective assessment.

In general, imaging is not always necessary for the diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy, and the diagnosis can often be made based on the patient’s clinical history and objective findings. However, imaging may be considered in cases where the diagnosis is unclear, or in cases where there is suspicion of more severe or complex pathology.

For example, imaging may be recommended if there is suspicion of a partial or complete tear of the Achilles tendon, or if the patient has failed to respond to conservative treatment and surgical intervention is being considered.

In general, ultrasound is often the preferred imaging modality for the evaluation of Achilles tendinopathy due to its high sensitivity and specificity, as well as its ability to provide real-time imaging of the tendon. MRI may also be used in cases where more detailed evaluation is necessary, although it is generally more expensive and time-consuming than ultrasound.

Ultrasound

is often the first-line imaging modality for Achilles tendinopathy because it is non-invasive, readily available, and can provide real-time imaging of the tendon. Ultrasound can be used to visualize the thickness and structure of the tendon, as well as any signs of inflammation or degeneration.

MRI

is another imaging modality that can be used to evaluate the Achilles tendon. It can provide more detailed information about the anatomy and integrity of the tendon, including the presence of tears or other structural abnormalities. However, MRI is more expensive and time-consuming than ultrasound, and may not always be necessary for the diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy.

X-rays

are generally not used to evaluate Achilles tendinopathy directly, as the tendon itself is not visible on X-rays. However, X-rays may be used to evaluate the bony structures around the tendon, such as the heel bone, to rule out other potential causes of foot and ankle pain.

Surgery

British Journal of Sports Medicine in 2015 evaluated the incidence of surgery for Achilles tendinopathy in a large cohort of patients in the United Kingdom. The study included 25,960 patients with Achilles tendinopathy who were treated between 1998 and 2013. Of these patients, only 558 (2.2%) underwent surgical treatment.

The study found that surgical treatment was more common in older patients and those with longer duration of symptoms, but was generally reserved for cases that had failed to respond to conservative treatments.

This study suggest that surgical treatment for Achilles tendinopathy is relatively uncommon in the general population, and is typically reserved for cases that have not responded to conservative treatments.

The decision to treat Achilles tendinopathy surgically depends on the severity and chronicity of the condition, as well as the patient’s symptoms and functional limitations. In general, surgery is reserved for cases of severe Achilles tendinopathy that have not responded to conservative treatments such as rest, physical therapy, and medication.

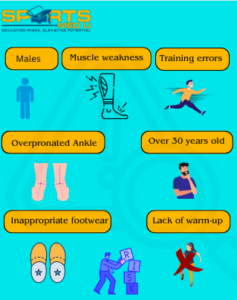

Risk factors Contributing To Achilles Tendinopathy Development

Understanding the risk factors for Achilles tendinopathy is essential as it allows for early identification of individuals who may be more susceptible to developing the condition. This knowledge enables targeted prevention strategies and interventions to mitigate modifiable risk factors, reducing the likelihood of Achilles tendinopathy occurrence and promoting overall tendon health.

I’d like to stress that these may increase the chances of developing Achilles tendinopathy, but it doesn’t mean that we should aim at fixing certain issues. Instead, the following points should only be used to increase in suspicion

Some factors to consider:

- Lack of warm-up before exercise can increase the risk, as it fails to prepare the tendon for the demands of physical activity.

- Increased frequency and duration of exercise without proper progression can overload the tendon and lead to injury.

- Poor technique and inappropriate footwear choices can alter biomechanics, placing excessive stress on the Achilles tendon.

- Weakness in the gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscles can disrupt the coordinated movements of the hip, knee, and ankle joints during the kinetic chain, which places more load on the achilles making individuals more susceptible to developing tendinopathy.

- The presence of an overpronated hindfoot or a varus forefoot has also been associated with Achilles tendinopathy, as it affects the alignment and mechanics of the foot and ankle.

- Males are more prone to Achilles tendinopathy, possibly due to the protective effect of estrogen in women against tendon pathology.

- Age is another factor, with the incidence of Achilles tendinopathy increasing with age, particularly in individuals over 30

Summary of article

- Achilles tendinopathy is a common condition characterized by posterior heel pain and affecting the Achilles tendon. It encompasses both inflammatory and degenerative aspects, which has led to ongoing discussions regarding its naming.

- There are two primary types of Achilles tendinopathy: insertional and non-insertional. The former is more prevalent in older, less active adults, while the latter is commonly seen in younger, more active individuals.

- Key facts about Achilles tendinopathy include the strength of the Achilles tendon, its susceptibility to peak forces during intense activities, and its prevalence among runners and soccer players.

- Training errors, such as inadequate progression, high-intensity training without sufficient rest, and excessive uphill or downhill running, contribute to Achilles tendinopathy. Proper warm-up, dynamic stretching, and varied terrain can help mitigate these risks.

- Recognizing the symptoms of Achilles tendinopathy is essential for early detection and accurate diagnosis. Stiffness, signs of inflammation, and a pain pattern during exercise are common indicators.

- The clinical course of Achilles tendinopathy often involves a gradual return to sport with controlled loading

and sufficient recovery periods. Balancing loading and recovery is crucial to promote healing and prevent further damage. - Imaging, such as ultrasound and MRI, may be used to evaluate Achilles tendinopathy in certain cases, but

diagnosis can often be made based on clinical history and examination findings. - Surgical intervention for Achilles tendinopathy is relatively uncommon and typically reserved for severe cases that have not responded to conservative treatments.

- Identifying risk factors for Achilles tendinopathy helps in early identification and targeted prevention strategies. Factors include inadequate warm-up, excessive exercise without progression, poor technique or footwear choices, muscle weakness, abnormal foot alignment, gender, and age.

Sources

- Grävare Silbernagel, K. and Crossley, K.M., 2015. A proposed return-to-sport program for patients with midportion Achilles tendinopathy: rationale and implementation. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 45(11), pp.876-886.

- Paavola, M., Kannus, P., Järvinen, T.A., Khan, K., Józsa, L. and Järvinen, M., 2002. Achilles tendinopathy. JBJS, 84(11), pp.2062-2076.

- Suan Cheng Tan & Otto Chan (2008) Achilles and patellar tendinopathy: Current understanding of pathophysiology and management, Disability and Rehabilitation, 30:20-22, 1608-1615, DOI: 10.1080/09638280701792268

- Tan, S.C. and Chan, O., 2008. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy: current understanding of pathophysiology and management. Disability and rehabilitation, 30(20-22), pp.1608-1615.

Leave a Reply